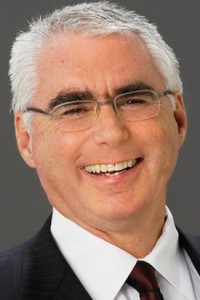

The Canadian government’s policies toward local research and innovation are being streamlined with industry, making it so researchers are no longer free to look outside the box. This is one of the reasons Dr. Robert Brownstone gives for his decision to leave Canada to live in England and teach at the University College of London.

Brownstone, who was born and raised in Winnipeg, has spent most of his research career in Canada. He is a neurosurgeon who has treated people with movement disorders, pain and epilepsy, and who researches neural circuits that control movement. Prior to recently leaving the country, he was working as a professor of surgery (neurosurgery) and medical neuroscience at Dalhousie University.

“While it could be argued that there have been no cuts to the Canadian Institutes and Health Research (CIHR), funding has been flat (which is in effect a cut) and funding has been directed to specific programs (which is a cut to investigator-driven fundamental research),” said Brownstone in an interview with the Independent.

Minister of State (Science and Technology) spokesperson Scott French challenged this claim, however. “Since being elected in 2006, our government has made record investment in science, technology and innovation to push the frontiers of knowledge, create jobs and improve the quality of life of Canadians – including providing over $1 billion in funding toward neuroscience research alone,” he said.

French added that CIHR directs two-thirds of its funding envelope to basic or discovery science to strengthen Canada’s position as a world leader in health research.

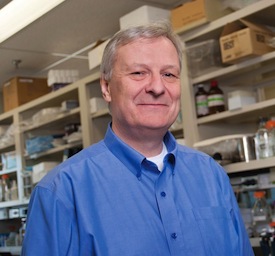

McGill University’s Dr. John Bergeron – researcher, professor and chair of anatomy and cell biology for 13 years – explained the issue using a hockey analogy. “For whatever reason,” he said, “we decided that talent and accountability to genuine discovery would not be part of our funding mechanism. That decision was made by administrators and, in my mind at least, it’s sort of like saying, ‘We’re going to get the best logos in hockey and that will make us win the championship, the NHL cup, or whatever.’ And saying, ‘We don’t need talent…. We just need to look good on camera.’ Of course, that’s not sensible.”

Bergeron acknowledged that generous sums of public money are targeted for research and development. However, he said that an accountability mechanism should be considered to see if that money is targeting talent that generates genuine discoveries.

“By any deductive measure, Canada is not doing well,” said Bergeron. “The most recent is the latest rankings of research universities (viewable at shanghairanking.com). We’ve had zero Nobel Prizes in medicine since our one and only award in 1923 (for the discovery of insulin). All big pharma pre-clinical research labs have left Canada and we have only one living Lasker Award winner – James Till of Toronto.

“It is the university presidents and heads of our funding agencies who have failed the Canadian taxpayer. It is young, genuine talent that is needed across Canada, and the lack of accountability of our university presidents and heads of funding agencies is what is holding us back.”

Bergeron said we are shooting ourselves in the foot by funding research without having an infrastructure to apply the discoveries and reap the rewards of our efforts. “One of my goals is to try to use the Merck labs, get them going to put together a world-class institute to exploit genuine discoveries that are made here in Canada.”

As an example, Bergeron pointed to the work of McGill University Canadian-Israeli educator Dr. Nahum Sonenberg.

“With Dr. Sonenberg’s basic science discovery, he went from figuring out all of the machinery involved in making proteins to stumbling across the fact that if you target a small molecule with some of the proteins he’s discovered, it improves memory. So, colleagues in the U.S. and Britain teamed up with biotechs and big pharmas and have now used this discovery to develop drugs to treat senility, Alzheimer’s, memory loss.

“This is going to be a market creating hundreds of millions of dollars that we’re not going to exploit [in Canada]…. We don’t have any infrastructure to do this, all because these crazy administrators know nothing about what real discoveries have been historically.”

Bergeron sits on grant panels for the European Commission that provide 10 million euro grants a year, as well as U.S. funding agencies panels that give out more than a million dollars in grants per year.

“When you’re in Canada, the average grant in the last competition for the open operating grant averaged out to about $125,000 a year per investigator,” said Bergeron. “That’s serious taxpayer money, but it’s not competitive with what’s going on in the rest of the world. We’re spending over $30 billion a year in research and development, yet we don’t use peer review. Funding decisions are made by administrators that know nothing about discovery.”

Jim Woodgett, investigator and director of research of the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital Joseph and Wolf Lebovic Health Complex, also said that funding has been stagnant in recent years and that restructuring at CIHR has resulted in further hoops researchers need to jump through to access funding.

“To access funds here, in Canada, you have to bring to the table equivalent funds from other sources,” said Woodgett. “They can be philanthropic sources, etc. These types of programs, the government has been quite keen on promoting as a means of leveraging additional support. And some types of research just don’t have that kind of accessibility or the researchers don’t have accessibility to those matching funds, so that does become a bit of a limiting problem.”

Woodgett said there needs to be a balance, and better ways to access funding that do not require fundraising. “You need to balance discovery research and applied research, otherwise what happens is you just dry up after awhile,” he said. “All the ideas dry up and there’s nothing then to translate into applied research.

“You can argue you should spend 10 percent of your funds on discovery and 90 percent on applied … and say that the private sector shouldn’t be funding basic science … they should be only funding applied science.”

Internationally, many government-supported research funds go toward the discovery end of the spectrum. Canada needs to do the same if it wants to retain top researchers, said Brownstone.

Acknowledging that he is not a politician nor an economist, he said, “I feel there is intrinsic value in knowledge or a knowledge economy. Good things come from knowledge. Just look at leaders in the field, like Switzerland and Silicon Valley, unlike oil economies, such as Saudi Arabia.”

As far as creating change and reinventing research in Canada, Brownstone said, “Changing culture is hard, but it can be done with leadership. Look at [U.S. President John F.] Kennedy and landing a man on the moon.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.