Not fitting in. Being misunderstood and miscategorized. These are recurring themes in Flying Camel: Essays on Identity by Women of North African and Middle Eastern Jewish Heritage, edited by Loolwa Khazzoom, a Seattle writer, musician, activist and occasional contributor to the Independent.

The book was first released in the 1990s and was recently re-released.

The book was first released in the 1990s and was recently re-released.

“I wish I could say that this book is no longer as revolutionary, cutting-edge, or as needed as it was when I began compiling it in 1992, but, unfortunately, that is not the case,” writes Khazzoom, the daughter of an Iraqi Jew, in the new introduction. “Even though there have been changes – shifts in consciousness, language, and even representation – Mizrahi and Sephardi women remain overall excluded, in theory and practice, from spaces for women, Jews, Middle Easterners, people of colour, LGBTQI folk, and even Mizrahim and Sephardim. In addition, so many of the presumably inclusive conversations about us seem basic and superficial, with an undertone of it being a really big deal that these conversations exist at all.”

Khazzoom’s struggle to fit in led her to Seattle, in large part because it is home to one of the largest Sephardi communities in the United States. But even in that milieu she found herself an outsider.

“In June 2014, however, on the first sh’bath [Sabbath] after driving my U-Haul up the coast from Northern California, I was appalled by a sermon so sexist – where women were equated with ‘meat’ – that I walked out of the Sephardi synagogue, just 15 minutes after arriving,” she writes.

“I have been a hybrid all my life, forever caught between two or more worlds,” writes Caroline Smadja in her contribution to the collection. It is a state of being that is shared by many of the writers.

Yael Arami, born in Petah Tikvah to parents from Yemen, speaks of others’ perceptions of her.

“In Germany, I have had to avoid certain areas, fearing local skinheads’ reaction to my skin colour. In France, I have been verbally ridiculed and insulted for being yet another ignorant North African who does not know French,” she writes. “In California, people’s best intentions have resulted in a number of social blunders: When I left a tip in a San Francisco café, I got a courteous ‘gracias’ from the politically correct Anglo waiter. After a predominantly African-American gospel group sang at a Marin County synagogue, several members of the congregation approached me, to express their admiration for our wonderful gospel performance! It seems that wherever I go in white-majority countries, I am, in accordance with local stereotypes, seen as the generic woman of colour – Algerian in France, African-American or Puerto Rican in California.”

Rachel Wahba, an Iraqi-Egyptian Jew, calls out politically correct hypocrisy.

“Sometimes, when I bring up the oppression of Jews in Arab countries, progressive Jews get strangely uncomfortable – as if recognizing the Jewish experience under Islam would make someone racist and anti-Arab,” she writes. “During my mother’s cancer support group intake, I listened as my mother told her story of living in Baghdad and surviving the Farhud. She ended with an ironic ‘I survived the Arabs to get cancer?’ The Jewish oncology nurse was shocked that my mother was so ‘blunt.’

“Should we revise our history? Leave out the details of our oppression under Islam? Pretend my mother never saw the Shiite merchants in Karballah wash their hands after doing business with her father, because he was a ‘dirty Jew?’”

The book’s title comes from an essay by Lital Levy, “How the Camel Found Its Wings” and an Israeli film of the same name.

The metaphor involves the repair of a broken statue of a flying camel, which actually stood at the entrance to the international fairgrounds in Tel Aviv in the 1930s. In the film, the two wings of the camel become stand-ins for a dichotomy that mostly excludes Mizrahi/Sephardi Jews and yet still casts them in a negative light.

“By the end of the screening, the camel had found two new wings, and I got to thinking,” writes Levy. “I started putting my own pieces together – making my own flying camel out of the remnants of the past, borrowing missing pieces from the present, and using my imagination and willpower to try to make it all stick together. The pieces of my own American childhood, the histories that preceded it in Israel and in Iraq, and the challenges I see before me in my work are the various fragments I have been remembering and re-membering into an integral whole. I do not yet know its shape – camel, dromedary, llama, yak – but I do not care, as long as it will fly.”

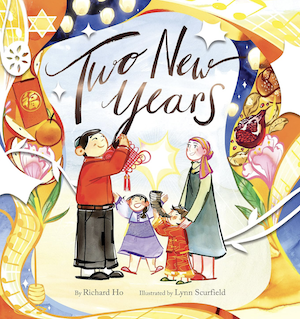

Ho has several kids books to his credit and, according to his website, more on the way. Two New Years highlights the differences and similarities between Rosh Hashanah and the Lunar New Year, both of which he celebrates.

Ho has several kids books to his credit and, according to his website, more on the way. Two New Years highlights the differences and similarities between Rosh Hashanah and the Lunar New Year, both of which he celebrates.