Letters that highlight friendship, writing that facilitates healing, stories that dissect societal mores – the books reviewed by the Jewish Independent this week represent only a small fraction of those featured at the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival this year.

While the official festival runs Feb. 11-16, opening with Dr. Gabor Maté in conversation with Marsha Lederman about his latest book, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture, there are a couple of pre-festival events this month: German writer Max Czollek launches the English version of his book De-Integrate! A Jewish Survival Guide for the 21st Century on Jan. 19 and American-Israeli photographer Jason Langer presents his book Berlin: A Jewish Ode to the Metropolis on Jan. 26. As well, there is a post-festival event, on Feb. 28, which sees former federal cabinet minister and senator Jack Austin launching his memoir, Unlikely Insider: A West Coast Advocate in Ottawa.

If the books reviewed by the Independent are any indication, attendees of the festival can expect to have their views challenged and their perspectives broadened; they will be moved, disturbed and amused, sometimes all at once.

Intimate portraits

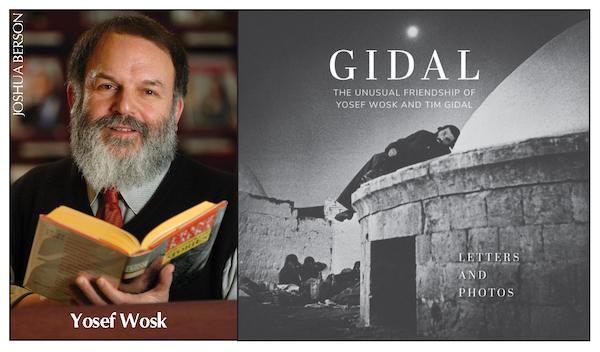

Two years ago, the JCC Jewish Book Festival featured the book Memories of Jewish Poland: The 1932 Photographs of Nachum Tim Gidal (jewishindependent.ca/gidals-photos-speak-volumes). It was the fulfilment of a dying request that Israeli photographer Tim Gidal made in 1996 to Vancouver scholar, writer and philanthropist Yosef Wosk. The book was released at the same time that an exhibit of its photos was mounted at the Zack Gallery (jewishindependent.ca/jewish-poland-in-1932).

The friendship between Wosk and Gidal was evident in that book and in the exhibit. How the two men – separated in age by some 40 years and in geography by almost 11,000 kilometres – became such good friends is the subject of Gidal: The Unusual Friendship of Yosef Wosk and Tim Gidal, written by Wosk (and, technically, Gidal) and edited by another of Wosk’s good friends, Alan Twigg.

The bulk of Gidal is letters that Gidal and Wosk wrote to each other from 1993, soon after they met, through to Gidal’s death in 1996. The postscript is a letter from Wosk to Gidal’s wife, Pia, mourning Gidal’s death and hoping that “his work and vision continue to inspire others.” Twigg has masterfully edited the multi-year correspondence, which comprised hundreds of letters, into an engaging narrative that offers insight into the core of these undeniably brilliant men, their work, ideas, loves, frustrations, sadnesses and more. Their vulnerability makes this a brave publication for Wosk to have created, and a meaningful one.

The other main component of Gidal is, of course, Gidal’s photographs, which, Wosk writes in the afterword, “serve as background to the letters.” As he did with Memories of Jewish Poland, Wosk mostly lets the photographs speak for themselves. Each photo section has a theme but each image within the section is simply captioned, placed and dated, without commentary.

There is a short chapter on Gidal and one on his and Wosk’s friendship and how this book came about. Gidal is creatively and esthetically put together. Each letter is headed by a key quote from the missive and the date it was sent. Images are included of some of the actual letters, most of which were sent by fax. It is interesting to contemplate whether this fount of communication would exist if it had been made via email.

Wosk and Twigg will talk about Gidal on Feb. 14, 7 p.m., at the book festival. The event is free of charge.

Therapeutic memoirs

Paired together for a presentation are Margot Fedoruk and Tamar Glouberman. The program categorizes them as “modern-day women” who will be presenting their “offbeat memoirs,” summarized by the question, “How B.C. is that?” Indeed, both Fedoruk and Glouberman tell coming-of-age stories of a sort, Fedoruk’s beginning in her 20s and Glouberman’s in her 30s. And they both lead outdoorsy, independent lives that could be described as the B.C. ideal, yet both have also faced many challenges and darker sides of that ideal.

Fedoruk is the author of Cooking Tips for Desperate Fishwives, in which she openly shares her anxieties of being married to a West Coast sea urchin diver – she is lonely without him, must raise their two daughters mostly without him and is worried that an accident may result in her having to live without him. Yet, she loves Rick, even though she does try (unsuccessfully) to convince him to take up another profession and stay closer to home. The pair moves around a lot, and Fedoruk herself takes up many different jobs over the years to make ends meet. But they stick together, getting married after their daughters are all grown up and have left home.

As dysfunctional as their relationship appears at times, Fedoruk had a more challenging life before she met Rick. Her father is a horrible man, her mother dies of cancer and she and her sister lose the family home to her mother’s second husband, also a horrible man. And there’s more. It is no wonder she leaves Winnipeg, eventually settling in British Columbia, though settling may be too strong a word, as she and her family do live in several different places on the coast, with some time in Calgary.

As dysfunctional as their relationship appears at times, Fedoruk had a more challenging life before she met Rick. Her father is a horrible man, her mother dies of cancer and she and her sister lose the family home to her mother’s second husband, also a horrible man. And there’s more. It is no wonder she leaves Winnipeg, eventually settling in British Columbia, though settling may be too strong a word, as she and her family do live in several different places on the coast, with some time in Calgary.

What makes Fedoruk’s memoir unique is the inclusion of a recipe in almost every chapter that reflects the mood or subject matter of the chapter, like the Killer Lasagne in the introduction, which begins, “The night I ran over Rick with my car, I was over four months pregnant with our first daughter.” Other recipes include Easy Curried Chickpeas With Rice, which appears as an affordable comfort food in a chapter about her being exhausted, on her own, caring for her two then-young daughters; and Wild-crafted Stinging Nettle Pesto, which comes after one of her descriptions of the soaps she makes – her business is Starfish Soap Company.

Near the end of her memoir, Fedoruk mentions that she has started therapy. I would have liked her to have written this book further into that process. As honest as she is about her feelings and circumstances, the memoir would have been more layered and impactful had she been further along in understanding how her traumatic childhood experiences, her genes and other factors affect how she moves through the world.

Glouberman has a less tragic background but a similarly transient life – and also loves something that gives her both great joy and great anxiety, the latter of which eventually takes over. In Chasing Rivers: A Whitewater Life, she shares her emotional journey of trying to make a life as a whitewater rafting guide.

One of the few women to guide tours, Glouberman does face sexism, her skills often underestimated by clients, but her male bosses and colleagues all seem to appreciate her abilities – certainly more than she does. She is constantly worried about making a mistake that will kill her or someone else and, while this is rational, given her job and its risks, the feeling becomes overwhelming. With an accident on the road – there is a lot of travel required to get to places like Chilko River, Williams Lake and further afield, outside the province – and her worst nightmare coming true on a rafting trip, Glouberman’s fears have very real incidents on which to grow.

One of the few women to guide tours, Glouberman does face sexism, her skills often underestimated by clients, but her male bosses and colleagues all seem to appreciate her abilities – certainly more than she does. She is constantly worried about making a mistake that will kill her or someone else and, while this is rational, given her job and its risks, the feeling becomes overwhelming. With an accident on the road – there is a lot of travel required to get to places like Chilko River, Williams Lake and further afield, outside the province – and her worst nightmare coming true on a rafting trip, Glouberman’s fears have very real incidents on which to grow.

Glouberman tries other types of work, but is always drawn back to the water. She struggles with depression and has a few other harsh experiences that add to her self-doubt. She tries various forms of therapy, some of which make her feel worse. Her family is supportive, though, and her sister’s home in Whistler is a refuge. She is only beginning her journey to healing when the memoir ends, and part of that has to do with getting into a master’s writing program. Both she and Fedoruk, who also went back to university for a writing degree, thank several people for their memoirs coming to fruition.

Glouberman and Fedoruk present at the book festival Feb. 12, 2 p.m. (tickets are $18). They also speak at Congregation Har El that day, at 11 a.m.

The price of victory

The harm inflicted on a society by war culture is front and centre in Israeli writer Yishai Sarid’s book Victorious. The main character, Abigail, is a military psychologist who, basically, tries to make soldiers into better killers, both “helping” them through trauma after they’ve experienced it and teaching them ways to be immune to trauma so that they can “beat the enemy.” Her father, who strongly disapproves of her work with the army, is a renowned clinical psychologist. On more than one occasion, he tries to talk her out of working for the military, but does not succeed. That the character of the father is dying of cancer is not coincidental.

Abigail blurs professional lines everywhere, working for the married man who fathered her son, the man who is now the army’s chief of staff; sleeping with a patient/friend; trying to become close friends with a former patient; and having a sexual relationship with one of the young soldiers whose unit she’s evaluating. The lessons she teaches are chilling, as is her abandonment of a patient who becomes too difficult for her to handle and some of her other actions.

Abigail blurs professional lines everywhere, working for the married man who fathered her son, the man who is now the army’s chief of staff; sleeping with a patient/friend; trying to become close friends with a former patient; and having a sexual relationship with one of the young soldiers whose unit she’s evaluating. The lessons she teaches are chilling, as is her abandonment of a patient who becomes too difficult for her to handle and some of her other actions.

She believes her job is her patriotic duty, even as her own son, Shauli, enters military service, in the paratroopers no less, and her fears for him fight with her pride in his choice. Though, with both his father and mother being staunch militarists, it could be argued that Shauli doesn’t really have a choice.

Victorious is a sparingly written novel that readers will not only ponder but feel well after they put it down. Translator Yardenne Greenspan must be given credit for making Sarid’s words as impactful in English as they are in Hebrew.

Sarid’s book festival event is Feb. 12, at 8 p.m. Tickets are $18.

For the full author lineup and to purchase festival tickets or passes, visit jccgv.com/jewish-book-festival or call 604-257-5111.