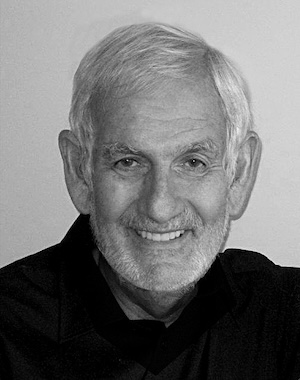

You may not know his name, but you certainly know his work. Vancouver Jewish architect Richard Henriquez has designed iconic local buildings including Eugenia Place in English Bay (the one with the pin oak on its penthouse terrace), the Sylvia Tower, the Sinclair Centre and the BC Cancer Research Centre. He designed New Westminster’s Justice Institute of BC, the UBC Michael Smith Laboratory, the UBC Recreation Centre and the Presidio. And that’s just scratching the surface of his 53 years of work in Vancouver, and well beyond.

Henriquez, 83, was born in Jamaica in 1941. That same year, his father, Alfred George Henriques, aware of the danger facing the Jews of Europe, joined the Royal Air Force as a bomber pilot. He did not survive the war.

One of Richard Henriquez’s earliest childhood memories is of a powerful hurricane that brought wind speeds of 150 miles per hour, devastating Jamaica’s north coast. At the time, the 3-year-old Henriquez was living on the north coast with his mother, grandmother and sister. “I still remember the sound of the metal roofing being torn off the roof, the screaming of the wind and the crashing of crockery being blown off the kitchen shelves,” he told the Independent. “The next morning, there were fish all over the yard and trees flattened everywhere.”

With their family home ruined, Henriquez and his sister joined their grandparents on a citrus plantation in Greenwood, Jamaica. Later, they moved to Buff Bay, to a new home with their mother and stepfather. Henriquez attended boarding school and Hebrew school in Jamaica. “Over the High Holy Days, I’d go to synagogue but I was never very religious,” he said.

By age 10, Henriquez had already decided on a career in architecture, a choice influenced by his grand-uncle Dossie, an architect, engineer and artist who would take him along on building visits. Rudolph “Dossie” Henriques, whose firm was Henriques and Sons, had designed the Kingston synagogue in 1912, after the original was destroyed by a 1907 earthquake. He also won a competition to design and build Jamaica’s Ward Theatre in 1912, and worked on the structural drawings for New York City’s Grand Central Terminal.

In 1958, after graduating from high school, Richard Henriquez left Jamaica to study architecture at the University of Manitoba. He returned to Jamaica after graduation and spent a couple of years working there before returning to North America to do a master’s degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1967. He then settled in Vancouver.

“My wife, Carol, is from Saskatoon, and she didn’t love Jamaica. She preferred to come back to Canada,” said Henriquez, whose time in Jamaica had a lifelong influence on his architectural style.

“In Jamaica, materials are expensive and labour is cheap, so I tend to want to renovate rather than tear down a house,” he explained. “I think that’s much more interesting than creating a new building. Later on in my career, I designed a couple of buildings that look like they were built a long time ago and renovated, like the Sylvia Tower in the West End.”

His talent as an architect has won Henriquez many accolades. In 1994, he won a Governor General’s Medal. In 2005, he won the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s gold medal. And, in 2017, he received an Order of Canada for his contribution to Canadian architecture.

“To me, architecture is about creating a unique place in the world,” he reflected. “Unlike West Coast modernists, who were inspired by light and connection to the outdoors, I was more interested in the specificity of a site, in researching the history of a site and incorporating it into the concept for a building.”

The Eugenia is a perfect example of Henriquez’s respect for the specific history and culture of a community. That 35-foot pin oak, brought to Vancouver from Oregon, represents a first-growth forest that covered the area decades ago. By incorporating it into the building, he paid homage to the landscape.

Henriquez’s son Gregory has followed in his footsteps and works alongside him at Henriquez Partners Architects in Vancouver, where Gregory Henriquez is overseeing the Oakridge Park complex in Vancouver, valued at over $5 billion. Richard Henriquez’s grandson is completing a master’s degree at the University of Toronto and will soon be joining the firm as the newest architect in the family.

Among his varied works, Henriquez designed Vancouver’s Temple Sholom Synagogue and, at one time, he had hoped to build something in Jerusalem, a goal that now seems remote.

These days, there are many projects competing for his time. A man keenly interested in genealogy, he traced his family history back more than 12 generations to Portugal, learning that his eighth-great-grandmother, Anna Rodriguez, was burned at the stake in 1643. He’s working on his second book on that family history, while also devoting time to art and sculpture, lifelong passions. Some of his work was on display at the Monica Reyes Gallery in Vancouver last month.

To learn more about Henriquez’s work, watch the 30-minute documentary Richard Henriquez: Building Stories on Shelter, an architecture streaming service. Commissioned by Marcon Developments, it celebrates his 53rd year of work in Vancouver and beyond. Also interesting to peruse is henriquezpartners.com/work.

Lauren Kramer, an award-winning writer and editor, lives in Richmond.