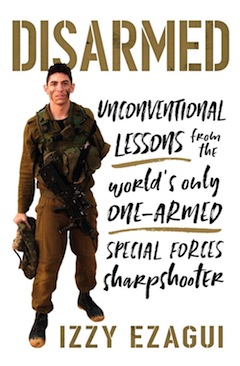

Disarmed: Unconventional Lessons from the World’s Only One-Armed Special Forces Sharpshooter by Izzy Ezagui (Prometheus Books) is confusing, puerile, uneven, exaggerated, chutzpadik and strident – I loved it. I enjoyed every blessed moment involved in reading this extraordinary Proust-like jumble of words and ideas by an Israeli soldier who lost his left arm in a Hamas mortar shelling a decade ago when he was on duty near Gaza.

The unlikely protagonist of this memorable saga is a Sephardi Jew raised in Florida and Crown Heights (New York), and educated first in the public school system and, afterward, in a Lubavitch yeshivah, before making aliyah. His father and mother, whom he idolizes in this book, were complex parents who decided, while Ezagui was still very young, to become more serious about their Judaism.

This autobiography is among the few books available on the intricacies of the Israeli army’s training procedures for inductees into elite units – which Ezagui experienced not once but twice – and, as such, it provides an introduction to what it really means to become a member of Zahal, the Israel Defence Forces. The rigours of IDF training are equal or superior to American, British and Canadian special forces cadres.

This autobiography is among the few books available on the intricacies of the Israeli army’s training procedures for inductees into elite units – which Ezagui experienced not once but twice – and, as such, it provides an introduction to what it really means to become a member of Zahal, the Israel Defence Forces. The rigours of IDF training are equal or superior to American, British and Canadian special forces cadres.

When Ezagui’s tent was destroyed by the mortar blast that hit his unit bivouacked near Gaza, the young soldier did not at first realize what had happened to him, so great was the shock to his nervous system. The graphic description he provides of the wreckage to his left arm is not easy reading because it lies outside our normal anatomical parameters but Ezagui conveys quite adequately the physical and psychic damage he endured. It took hours before the extent of his personal catastrophe was fully known.

Ezagui’s comrades were able, once the dust had cleared, to transport him to an Israeli medical facility, where doctors stabilized the young soldier, along with others who had been injured by enemy fire. One of the most poignant parts of this journal is Ezagui’s attempt to speak to his mother on the telephone to impart the news about the loss of his left arm without provoking hysteria on her part.

Part of the treatment the author received from Israel’s medical cadres were heavy doses of very powerful drugs, including fentanyl, a narcotic, he notes, which is a hundred times more potent than morphine; it was the first drug administered to him when the severity of his injury was recognized. This is a relevant observation because, when Ezagui began to recover his sensibilities, he immediately declared that he intended to return to his combat unit. But he soon realized that he would have to go “cold turkey” before he could even think of rejoining his comrades. This he did by dint of unbelievable discipline in the face of incredible suffering from withdrawal.

During this crisis period in his slow recovery, Ezagui was confronted with the negative responses of army doctors, one of whom bluntly told him that his condition precluded the kind of camaraderie and fraternity among soldiers who depend on their peers to help them. That kind of subtle yet direct rejection ironically made Ezagui more determined in his pursuit of his former status as a soldier-sharpshooter. It did not help that he was continually hounded by his “phantom,” the curious physiological phenomenon when a severed limb asserts its presence despite its absence.

In his narrative, Ezagui gives us all the excruciating details of his retraining in the army – this time, with a limb missing. One of the greatest obstacles he encountered was mounting a wall with a rope anchored to it. In his previous incarnation, he had no problem, but one arm wasn’t enough to execute the onerous task. He finally realized that a contortionist’s skill was required to perform the feat and, through the use of his legs and other body parts, he was able to get over the wall.

Ezagui encountered a similar problem with his rifle. It jammed regularly when he tried to insert the shells into it. He overcame his frustration only when he realized that he had to dig his weapon into the ground, anchor it solidly and, then, with his one arm, load the instrument.

Ezagui passed all his retraining requirements and it was the doctor who had initially rejected his attempt to rejoin his unit who certified his reentry into the army.

Disarmed is a testimony to the resilience of one human being who beat the odds and conquered a disability, and Ezagui has become a symbol of what the human spirit is capable of accomplishing.

Arnold Ages is Distinguished Emeritus Professor at University of Waterloo, in Ontario.