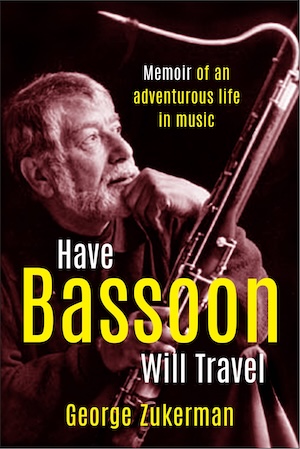

The reasons why Wendy Atkinson, who owns Ronsdale Press, wanted to publish Have Bassoon Will Travel: Memoir of an Adventurous Life in Music by the late George Zukerman, are the reasons people should read it. Zukerman had a long and impressive solo career as a bassoonist, was a pioneer in organizing concerts and tours, and gave remote communities across Canada the rare chance to hear classical music performed live.

“She recognized that his anecdotes capture a vital period in Canada’s musical history and are vivid reminders of the lengths musicians will go to tour our vast country,” reads the afterword. “George’s memoirs go beyond simply capturing a life. He expanded the cultural reach of classical music in Canada; no small feat and Canada is better for it.”

How Zukerman’s memoir came to be is an example of the communities he created in his life. When he died Feb. 1, 2023, in White Rock, the manuscript had been written, but it took several volunteers – each with their own connections – to bring it to publication quality and get it printed. After reading Have Bassoon Will Travel, you will know why they did it. Not only was Zukerman a world-class musician and impresario, but he was a world-class human being: humble, funny, innovative, hardworking, fairness-driven, adventuresome, the list goes on.

How Zukerman’s memoir came to be is an example of the communities he created in his life. When he died Feb. 1, 2023, in White Rock, the manuscript had been written, but it took several volunteers – each with their own connections – to bring it to publication quality and get it printed. After reading Have Bassoon Will Travel, you will know why they did it. Not only was Zukerman a world-class musician and impresario, but he was a world-class human being: humble, funny, innovative, hardworking, fairness-driven, adventuresome, the list goes on.

Zukerman was born in London, England, on Feb. 22, 1927. Well into the book he talks about how he never liked his name, George – his parents, both American citizens living abroad, named him after the United States’ first president, George Washington. His middle name, Benedict, was in honour of 17th-century Jewish philosopher Baruch (Benedict) Spinoza, who was expelled by his community for his ideas. Zukerman also discusses his surname, the spelling of which differs across family thanks to the North American melting pot. There is something to be said about living up to one’s name, and Zukerman certainly was a leader in his fields of music, both as performer and impresario; he certainly forged his own path, uplifting the place of the bassoon in the orchestral world, creating opportunities for fellow musicians to perform and bringing classical music to the remotest of areas; and he lived in several places and traveled, mostly for work, around the world.

It is incredible how much of life is directed by (seeming) happenstance. Zukerman’s first encounter with the bassoon was at 11-and-a-half years of age. It was an accidental meeting, as his older brother showed him around the London prep school Zukerman was about to attend.

“We wandered past the windows of a basement chapel and glanced down to where an orchestra was rehearsing,” writes Zukerman. “A row of tall pipes seemed to reach for the ceiling. I could see and hear very little through the moss-covered stone walls and grimy opaque windows of the old school, and I wondered what on earth these strange-looking instruments were. My brother, already in Form IV, authority on much, including most musical matters, declared them to be bassoons, and the piece in rehearsal the annual Messiah. We walked on to explore my new school, and any awareness that I would spend my life playing that instrument would have been uncannily prescient. The bassoon remained buried deep among early memories.”

His next encounter was as random. As the Second World War began, the family – less Zukerman’s journalist father, who joined later – left London for New York City. There, Zukerman attended the newly established High School of Music and Art.

“By way of an audition,” he shares, “I played [on the piano] my one and only party piece (a simple Beethoven sonatina). To my surprise as much as anyone else’s, I was admitted to the class of 1940! Dare I suspect that my acceptance had as much to do with short pants and an English accent as with any evident musical skill?”

On the first day of school, the kids were told to pick an instrument. “No British prep school could have readied me for such democratic and independent action, so I hesitated,” writes Zukerman. “On all sides of me, the pushy American kids ran furiously and grasped what they could most easily identify. The violins, clarinets, flutes, trumpets, cellos and drums disappeared into groping hands. When I finally reached the shelf, all that remained was an anonymous black box. I lifted it gently and carried it toward a teacher standing nearby. ‘Excuse me, Sir,’ I asked timidly, ‘but what is this?’

“He looked down, and a broad smile covered his face. ‘Why, you are our bassoonist!’ he declared.”

With faint remembrance of the tour with his brother, he thought, “Was I now going to play such an instrument?”

Indeed, he was, and to eventual great acclaim, both as part of orchestras and as a soloist. But, as you can imagine, bassoonist was not exactly a living-wage career, at least not in Zukerman’s time, and his parallel career arose from a need for more work. Having learned during his time with the St. Louis Sinfonietta in the 1940s about community concerts – where money was raised in advance through subscriptions rather than individual ticket sales, and no contracts were signed until the money to pay for everything had been raised – Zukerman, who was by then living in Vancouver, brought the idea to Canada. His offer to an American company to be their representative here declined, Zukerman decided to do it on his own.

“Canada was coming of age, and Canadian communities were ready to make their own concert plans and to welcome Canadian groups and soloists, even if at the time they were equally unknown,” he writes. “Within a decade, Maclean’s magazine would write that I had successfully outsmarted the Americans at their own game.”

It is fascinating to read of Zukerman’s efforts to expand the reach of classical music in Canada and other countries – he visited the Soviet Union eight times between 1971 and 1992, as performer and concert organizer, and brought Soviet musicians to Canada to tour. Decades earlier, he spent a year-plus in Israel, part of the nascent Israel Philharmonic. He was also part of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra in its early days, and of the Vancouver Jewish community – Abe Arnold, publisher of the Jewish Independent’s predecessor, the Jewish Western Bulletin, had a small but notable impact on Zukerman’s life.

Have Bassoon Will Travel is a truly engaging read. The way in which Zukerman writes is like how he would have spoken, though likely more concise and organized. The effect is that we the reader are having a chat with him, reminiscing. We get a feel for what life was like back in the day for a musician and entrepreneur. We feel nostalgia for a time many of us never experienced personally.