It was heartbreaking to read Rabbi Denise Handlarski’s op-ed titled “Harris-Emhoff’s significance.” [Jewish Independent, Nov. 27] Heartbreaking, yes. Shocking, unfortunately, not at all. Almost every single Jewish family, including my own, has a relative or close friend who has intermarried or has seriously contemplated intermarriage were the opportunity to present itself. A 2017 Jewish People Policy Institute study shows that, in the United States, 60% of non-Orthodox Jews, aged 40-44, are intermarried. In the 35-39 age bracket, 73% are intermarried; the percentage rises to 75% when dealing with those between 30 and 34. We are clearly witnessing a dramatic upward trend.

Rabbi Handlarski, ordained by the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism, an institution that focuses on living a life with a cultural Jewish identity through a “non-theistic philosophy of life,” expresses her excitement over this popular trend and its prevalence among families of our global leaders. She writes, “Jewish communities have spent the past several decades trying to stop intermarriage. These efforts have failed…. It’s time we embrace our pluralistic and diverse families….”

It is true: we have failed. We have failed as a people to teach about the centrality of Judaism in our lives, the impact we, as a small nation, have made upon the entire world, the destiny of our future and the need to secure our traditions, beliefs and values within our families.

However, as a believer in God and the mission that we, the Jewish People, were charged with more than 3,000 years ago, the embracement of a non-Jewish spouse is: 1) an option that is simply not on the table and 2) even if it were on the table, the acceptance of such marriages is a recipe for failure for anyone with an interest to preserve Judaism.

Why is intermarriage off the table?

There is a well-known atheist, European author and philosopher Alain De Betton, who speaks about Atheism 2.0, a version of atheism that also incorporates our human need for connection, ritual and transcendence. He believes that religion adds a great deal to the world, but he just doesn’t believe in God.

De Betton articulates a defence of the halachic system that is both true and profound. He states: “The starting point of religion is that we are children and we need guidance. The secular world often gets offended by this. It assumes that all adults are mature – and, therefore, it hates didacticism, it hates the idea of moral instruction. But, of course, we are children, big children who need guidance and reminders of how to live. And yet the modern education system denies this. It treats us all as far too rational, reasonable, in control. We are far more desperate than secular modernity recognizes. All of us are on the edge of panic and terror, pretty much all the time – and religions recognize this.”

I once heard an insightful comment from a rabbinic teacher of mine: the word “mitzvah” has two very different connotations – a good deed and an obligation. For an action to be a good deed, it just needs to embed an inherent goodness. To fulfil a commandment means that there is a Commander. As soon as I acknowledge that I am doing a mitzvah, I am metzuvah – I am commanded and there is a Commander. Therefore, God’s word comes before mine.

Even if my rationale leads me to the conclusion that intermarriage expresses the positive values of acceptance and diversity, God has already decided that other values, perhaps unbeknownst to humankind, outweigh it. Maimonides, the 12th-century leading philosopher and codifier of Jewish law, writes in his code of law: “There is a biblical prohibition when a Jew engages in relations with a woman from other nations, [taking her] as his wife or a Jewess engages in relations with a non-Jew as his wife. As [Deuteronomy 7:3] states: ‘You shall not intermarry with them. Do not give your daughter to his son, and do not take his daughter for your son.’”

In truth, the conversation should stop here; it is a law from God and there is nothing more to discuss.

Why is intermarriage destined to fail?

However, not all of us find the word of God a compelling argument, or believe in His existence to begin with. To that group, the statistics should speak for themselves.

Rabbi Handlarski admits that there are very real grounds to fear assimilation, but, she argues, Jewish pride and identity can and does exist within many intermarried families. However, a 2013 Pew Research study showed that more than one in five Americans identify themselves as without a religion, more than two-thirds do not have any affiliation with any synagogue, and more than a third believe that Jesus being the Messiah is compatible with Judaism. The average Jew in North America knows who Jesus and his mother were, but they cannot name our forefathers, foremothers and who was married to whom. The average Jew knows more about Christmas carols than they do about Jewish liturgy.

Doron Kornbluth, author of Why Marry Jewish, writes that even among intermarried families who raise their children as “Jews only,” a mere 11% of those children would be very upset if their own kids did not view themselves as Jewish. The fears of assimilation are very real indeed, and there is an undeniable and direct causal link between intermarriage and assimilation.

Former British chief rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory, in his book The Dignity of Difference, writes that the prohibition to intermarry is not racist or intolerant; just the opposite! Without diminishing our love and concern for any fellow Jew, irrespective of her choices, Rabbi Sacks explains that, in our day, global cultural homogenization threatens to

destroy all minority groups and their culture. When we have a bit of everything, we represent nothing. This global phenomenon impacts many minority cultures and limits their impact on the broader world. In order for the Jewish people to continue to spread their values and be a light onto the nations, we must secure and safeguard our tradition from the threat of homogenization. We must first ignite a light before it can shine on others. To choose “romantic” love over faith is to set the trajectory for all future descendants towards a path of Jewish annihilation.

Finally, a few years ago, a guest rabbi lecturer was speaking here in Vancouver. He told the following story. A few years back, he was speaking to university-aged students and, a few minutes into the talk, a young woman raised her hand and said: “Rabbi, we are in attendance today for you to

answer just one question: Why should we marry Jewish?” He responded, “The question is not, Why marry Jewish? The question is, Why isn’t Judaism the central and integral part of your life such that ‘Why marry Jewish?’ is not even entertained as a question?”

The real question we must ask ourselves is, What does it mean to be a Jew? Are we culturally Jewish? Are we socially Jewish? Is our Judaism the same thing as Zionism? History has proven that none of these defines Judaism. Judaism has existed for thousands of years, and the state of Israel is but 70 years old. A Jew from Eastern Europe lived a drastically different cultural life from the Iranian Jew. Judaism is a charge that we were given at Mount Sinai to live a life in service of God, to better the world, and to pass the commandments and values down from generation to generation. It is a heavy responsibility, but history has proven that we can persevere with great pride and fulfilment.

Today, Dec. 18, is the last day of Chanukah. Ironically, if we saw any beauty in intermarriage as Rabbi Handlarski views it, then there would be no holiday, no celebration. The essence of Chanukah is about strong-willed Jews and their ability to withstand the pressure of Greek culture and to retain their identity. “Maoz Tzur,” the song that we sing when lighting the menorah, is all about the survival of the Jew throughout the centuries and our ability to maintain not just some of our values and traditions, but all of them. The solution is not to accept defeat. The solution is to become more aware of our history, understand what it means to be a Jew – today and every day – and live towards a viable future.

Rabbi Ari Federgrun is associate rabbi at Congregation Schara Tzedeck.

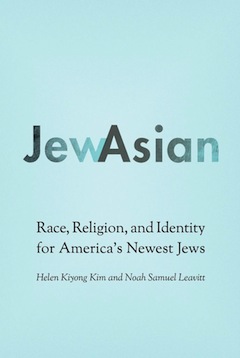

“We focused there, in part, because of the high percentages of individuals who identified as Jewish and Asian,” said Kim. “Then, there was the likelihood and demographic reality that interracial marriages are taking place predominantly in those areas … with the West Coast having, by far, the highest rates of interracial marriages.”

“We focused there, in part, because of the high percentages of individuals who identified as Jewish and Asian,” said Kim. “Then, there was the likelihood and demographic reality that interracial marriages are taking place predominantly in those areas … with the West Coast having, by far, the highest rates of interracial marriages.”