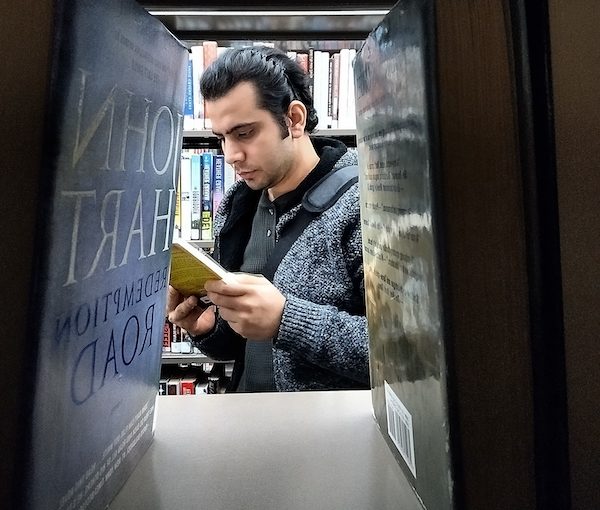

Khalid Aziz (photo from Khalid Aziz)

Khalid Aziz got out of Afghanistan about six weeks before the government fell. Eighteen months later, he has a job here at a local café/bakery and works part-time with a local advisory group on refugees called Diverse City. In his spare time, he volunteers with Jewish Family Services, who he considers family, and attends JFS events.

“Khalid is amazing. He just lights up the room when he walks in,” said Emi Do, former supervisor of the Community Kitchen.

Recently, Aziz planned and led a JFS Community Kitchen event, where he taught participants to cook Afghan dumplings.

“It’s all about community building, celebrating and sharing skills and knowledge about food,” said Stacy Friedman, director of food security at JFS, about Community Kitchen events, where people meet and cook together. She hopes the program will pick up again later this spring.

“Khalid has a very warm presence and is a good communicator,” she said.

But how did Aziz connect with JFS in the first place?

When he was still new to Vancouver, Aziz found the JFS and Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver websites. He also heard on the news that Israel was taking in 150 to 200 Afghan refugees. That caught his attention and he wanted to find out more about the local Jewish community, so he contacted JFS and spoke to case manager Corrina Frederick. He was going through a rough time and Frederick was happy to listen to him.

“She showed so much empathy towards me … it was unbelievable,” Aziz said.

Soon after, Aziz was invited to a JFS Community Kitchen event, where he chatted with one of the other volunteers.

“While having our coffee, my friend asked me whether I was a Jew. I replied with Muslim. She was surprised and happy that I was among them, sitting next to each other in a beautiful atmosphere, with no hesitation, which was quite amazing to me,” he said.

Since then, Aziz has learned a lot about the Jewish people.

“Obviously, Judaism believes in one God. And its history is phenomenal. And what I learned and liked about the Jewish people is that they practise fasting, almsgiving and follow the dietary laws.” He also learned that Judaism uses the word kosher in the same way that Muslims use the word halal.

Aziz’s gratitude to JFS knows no bounds.

“The JFS assisted me with employment sources and invited me to their educational programs, as well as different events, to have the utmost experience in B.C. It really gives me pleasure to be a part of the Jewish Family Services, which helps others to achieve their goals and live peacefully.”

This is in stark contrast to his life in Kabul, where he received letters containing death threats from the Taliban for his work at the National Bank of Afghanistan, on U.S. embassy projects and at the United Nations, where he supervised and led 16 staff members involved in agriculture projects.

“Definitely, like many others, my life was in danger, without a doubt,” he said. And so were the lives of most of his family members, who were working with other organizations.

While most of his family are now living safely in different countries around the world, Aziz, 30, is still reeling from his experience getting here, and finding food and shelter.

To escape from Kabul, in July 2021, Aziz traveled to Pakistan to apply for a student visa in the United States. He successfully passed his interview at the U.S. embassy and was granted a visa one week before the Afghan government fell. With the help of family and friends, he traveled to the United States to live with his sister.

Due to the financial crisis in Afghanistan, his bank account was frozen. He waited five months for support from the American government. When that fell through, he decided to come to claim asylum in Canada.

It was nightfall and Aziz was able to avoid the U.S. border guards.

“Luckily, I made it to the border and entered Canada with happiness and hope for a better life and leaving all my stress and anxiety behind the crossing line,” he said.

The Canada Border Services Agency stopped him and cuffed him, but told him not to be afraid. They also told him that there was homelessness in Canada and he had better be prepared for that.

Aziz has no ill feelings towards the CBSA, saying they were kind in changing his handcuffs around so that he could have a drink of water.

Even though he had $1,000 when he reached Vancouver, all the hotels he found would only accept debit or credit cards. “After one hour of roaming and looking around for hotels, I ended up spending my night on a footpath downtown in the cold weather of February,” he said.

It was a tough month for Aziz, staying at shelters. “I wasn’t able to sleep well in my first month due to the inappropriate place, with no privacy and I was emotionally and mentally disturbed and stressed about what was going to happen next,” he said.

Aziz finally was able to rent a room and he bought job interview clothing while managing at the same time to volunteer for the Muslim Food Bank as a case worker and translator for refugees – he speaks several languages, including Pashto, Farsi, Urdu, Hindi and basic Arabic.

After about four months, Aziz found a job and, today, lives in a two-bedroom apartment with a roommate in Burnaby.

Aziz hopes to engage in more refugee-related work locally, as well as with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Cassandra Freeman is an improv teacher and performer living in Vancouver.