Ilana Zackon and Ariel Martz-Oberlander played current-day partisans in the immersive theatre piece Time Machine. (photo from Radix Theatre)

Two Jewish theatre artist-creators, Ariel Martz-Oberlander and Ilana Zackon, teamed up this summer to create an immersive piece based on the Jewish partisan movement, as part of Radix Theatre’s futuristic play Time Machine, set on a boat, the Pride of Vancouver.

The show took place on the yacht over a five-hour journey up Indian Arm (traditionally known as səl̓ilw̓ət) and featured both local emerging and established artists presenting new work of various genres, such as theatre, spoken word poetry, sound installation and more. The artists were asked to create a piece inspired by what Vancouver will look like in the year 2050. Some darker, others playful, the works were all grounded in a strong sense of the artists’ identities.

Martz-Oberlander and Zackon wanted to bring their ancestral roots into their piece. The pair created an immersive show in which they played two rebels helping smuggle climate refugees to safety. The 10-minute piece, which ran on a loop for an hour-and-a-half of the boat ride, took place in the boat’s basement bathroom, which acted as a safehouse. Five to seven audience members at a time were summoned by Zackon, dressed as a soldier, down into the dimly lit bathroom, where they were greeted by a similarly dressed Martz-Oberlander; “Zog Nit Keynmol” (“The Partisan Song”) played in the background.

The invited audience soon discovers they are now refugees who have just escaped fires in California. The soldiers, members of a new wave of partisans called PAP, explain that the refugees are being brought to another safehouse and prepared to enter the new world. The soldiers explain that their resistance cohort has based their movement on the survival lessons of their ancestors, partisan fighters in the forests of occupied Europe. The audience members are given new names, briefed on the types of skills, such as hunting moose, that they will need to survive in their new lives and, eventually, led into a discussion on identity.

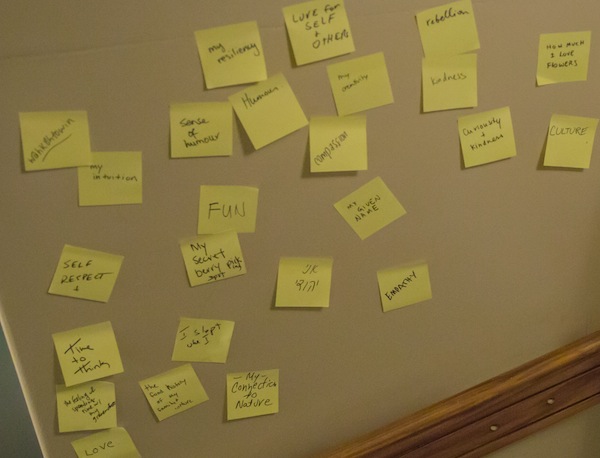

“What’s better: start over or remember where you’re coming from?” Martz-Oberlander’s character asks. The two soldiers bicker over their differing views and invite the audience to contribute. After the group has spoken, the soldiers receive word that it is safe to move the refugees. Before leaving, audience members are given the option of writing down “one thing about their identity they don’t want to lose in the new world” on a sticky note. The notes lined the stairwell and, as the loop continued, more and more words were added, creating a tapestry of human identity. The notes lined the bathroom walls for the remainder of the boat ride, and included such items as “curiosity and kindness,” “time to think,” “my favourite berry picking spot,” “my knowledge of languages” and “the giggles of my daughter,” among many others.

A number of the boat passengers who attended the piece were Jewish and shared how they connected with their ancestors through remembering their stories. Many non-Jews had never heard of the partisan movement and the two artists felt the work they did helped educate people on an important part of history.

Zackon and Martz-Oberlander also received, from the Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia, transcripts of interviews with Jewish refugees coming to Canada during the 1930s and 1940s. These testimonials were hidden around the safehouse and incorporated into the performance. The two artists hope to receive the opportunity to continue developing and expanding this work and to incorporate more of their own personal family stories about immigration to Canada.