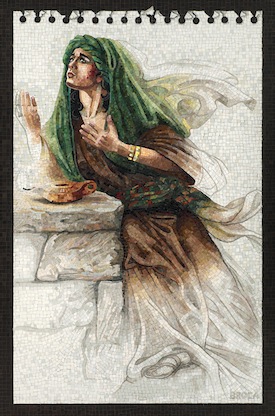

Lilian Broca stands with “Mary Magdalene, The Sacred Union,” which is one of seven panels comprising her current exhibit, Mary Magdalene Resurrected. (photo from Lilian Broca)

Lilian Broca’s artistic canon includes four series on biblical women. The latest, Mary Magdalene Resurrected, is at Il Museo at the Italian Cultural Centre until Aug. 15.

“Each series is an interpretation of a different concern,” Broca told the Independent. “Lilith is the rebel signifying hope for human courage and gender equality. Queen Esther, also courageous and wise, her story addressing the theme of sacrifice and self-empowerment, is actively involved in politics; in her time, known as an almost exclusive masculine realm. Judith, a warrior at heart who single-handedly saves her town from total annihilation, speaks of female effectiveness in the military world – a masculine tradition that she breaks, proving women don’t necessarily excel only in the domestic sphere.

“Unlike Esther and Judith, both actively involved in the masculine domain, Mariam [Mary] is a much more complex figure,” said Broca. “Her story has been greatly redacted in the first couple of centuries CE, leaving us various versions, which offer divergent perspectives of her importance and placement in the life of Yeshua Ben Yosef [Jesus]. One of the concerns in this series is about women’s place, or lack thereof, in institutions – which even in our 21st century – are restrictively based on gender.”

While it may seem odd that Mary Magdalene is included in Broca’s body of work, she reminded the Independent that Mary was “also Jewish until she died, as Christianity did not appear as such until the Edict of Milan in 313 CE and, universally, only at the Council of Nicea in 325 CE.”

A painter for many years, Broca’s Lilith series was created and exhibited in that medium, while Esther, Judith and Mariam are portrayed in mosaics.

“In 2000, I attended The Creation of the World in Jewish and Christian Art with Discussion on Illuminated Manuscripts at the Vancouver Public Library with speakers/presenters Bezalel Narkiss and Dr. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, both of Israel,” explained Broca. “There, I saw a slide show Bezalel presented on ancient synagogues in the Levant. The Dura Europos in Syria had a beautiful fresco illustrating the Queen Esther story. I was mesmerized and, once home, I started to do some serious research on the Esther stories (more than one version)…. It was during the research that I found out that the palace in which Esther lived with her Persian king, Hashayarshah/Xerxes, had floors ‘encrusted with rubies and porphyry in pleasing designs.’ These were mosaics and, for me, a good omen. I knew I should return to creating mosaics one day, something I experimented with as a student (at 19) but stopped soon after. So, I decided to create the whole Esther series in mosaic glass.”

More than 10 years ago, Broca’s interest in Mary Magdalene was piqued by something she read on the discovery in the 1940s of the Gnostic Gospels, but various circumstances delayed further study, including a visit to her studio by Dr. Adolfo Roitman, curator of the Dead Sea Scrolls, who was in town to give a lecture. He loved the Esther series and suggested she do one on Judith, which she did.

Only in 2016 did Broca return her attention to Mariam. Over eight months, she read dozens of books and essays, and drew and painted the cartoons (drawings for mosaics) for the series now on display. In making the panels, Broca had the help of Adeline Benhammouda, who used to work for Mosaika Studio in Montreal. When Broca was diagnosed with cancer, she asked the studio to make the last two mosaics in the series.

“In the meantime,” said Broca, “the pandemic slowed down activities in all institutions, especially art galleries, and I didn’t know what would happen to my future exhibition.”

The pandemic also temporarily reduced the supply of N95 masks that protected Broca – who suffered a lung infection after her radiation treatment was complete – from the silica dust that results from grinding the glass mosaic tesserae.

One of Broca’s projects as a Shadbolt Independent Scholar at Simon Fraser University was to write a letter describing her activities during the self-isolation months of COVID. All the scholars’ letters were published and Broca’s can be found at the bcreview.ca/2021/02/14/broca-pandemic-magdalene. It is addressed to Mariam and, in it, Broca explains why she chose large (79-by-48-inch) panels for this series.

“In the past, women artists, their works and their stories were mostly associated with the intimate and the small, as though they dared not take up valuable space and time,” she wrote. “As you know from my past art works, I resent that timid notion. My heroines insist and demand the space and importance that long ago was offered to masculine achievements in the military, politics and commerce.

“And, finally, Mariam, after reading so many diverse accusations, betrayals, and the vilification you were subjected to over the centuries, I have decided to express the existence of disparate accounts of your story with text in each mosaic panel, hence the illuminated manuscript composition and unifying motif. Each panel displays three to four lines in an ancient language spoken during your time on earth.”

The languages featured are Aramaic, Hebrew, Ancient Greek, Armenian, Latin, Amharic and Coptic. Broca chose to make seven panels because seven “is a sacred number in the Jewish tradition.”

“Symbolism plays an important part in my artworks and this series is no exception,” Broca told the Independent. “Each drawing includes symbols that are meaningful in both Judaic and Christian traditions. Whether they are flowers, fruit, boats, pottery or textile patterns, these symbols speak of the distant past, yet most of them are recognizable today. Just like an illuminated manuscript page, I sought to illuminate what lies hidden or repressed through the symbols on the borders of each ‘page.’ Hopefully, through them, new ideas can be brought to life.”

While the Esther and Judith stories have a beginning and an end, Broca said, “Mariam unfortunately is a figure that appears suddenly in Yeshua’s (arguably) 33rd year and disappears right after the Crucifixion that same year. The Gnostic Gospels and other historical documentation that refer to her following the crucifixion are interwoven with legend and myth, none of which is accepted by academics. I chose scenes from all sources, scenes that I felt relayed best her high social status during Yeshua’s life, the love and closeness the two shared, her marginalization once Yeshua died and there was no one to protect her against the ill will and jealousy of the Apostles, the relationship with Mary the Virgin and, finally, my personal vision of a balanced religion, any religion.”

For the series, Broca studied the history of the Jews in the first-century BCE to first-century CE period. “I loved all that research,” said Broca. “I learned so much about Judaism in the process. It was reassuring to read Yeshua’s Jewish parables and to realize that he was very, very concerned with the lack of faith he found in the small beit hamidrash(es) they had in those days and, of course, in the temple. The political situation at that time was extremely complex and the ‘ruling class’ of Sadducees and Pharisees kept the masses in poverty while most of them aligned themselves with the Romans and became wealthier than they had ever dreamed. Yeshua never planned on starting a new religion; on the contrary, he wanted a return to the old ways. My understanding is that the 12 disciples were responsible for all the changes that ensued after Yeshua’s death.”

During the drawing stage of the series, Broca said she consulted two academics – Dr. Mary Ann Beavis and Margaret Starbird – about “‘how far can I push the envelope?’ before I get reprimanded by Christians for profanity or blasphemy.” For instance, wondered Broca, is it OK to portray Jesus washing Mary Magdelene’s feet?

“Each time I heard their answers,” said Broca, “I weighed them carefully, because, after all, I do retain an artistic licence for expressing my own perspective in art. But, at the same time, as a Jewish woman (not a Jewish artist) who embarks on a sensitive subject, I had to make sure I respect the Christian beliefs. I would not appreciate a Christian person making art that endorses what I consider derogatory Jewish images or symbolism.”

At the exhibit’s opening, Broca said, “I am not a theologian nor a religious person and my point of view remains, as always, a feminist one.”

She noted, “Mary Magdalene lived in a strict patriarchal society when women had few rights and freedoms, yet she left her sanctuary, her home and family, in order to follow a single man, without a job or an income, without a fixed address, a man traveling with an entourage of 12 other men spreading the word of God.”

She said, “For 20 centuries, Yeshua, or Jesus, has been both a bridge and a barrier between the Jewish and the Christian faiths. Although I find Jesus equally fascinating, this body of work here, is not about him. It is strictly about his favourite and beloved disciple, Mary the Magdalene.”

The documentary Mary Magdalene in Conversation with Lilian Broca is in post-production. The film, for which Broca wrote the script, is fully subsidized by the Canada Council for the Arts. It follows the journal Broca started in early 2016, when she embarked on her research.

“My hope is that the Mary Magdalene series will open new avenues to perceive the hugely influential relationship between Yeshua and Mariam … as well as considering what happened to that relationship in the hands of the male founders of Christianity,” said Broca. “In addition, I hope that, through my Mariam mosaics, viewers will be profoundly motivated to reexamine this whole critical episode of human history.”

In a 2020 article, Italian Cultural Centre director and curator Angela Clarke spoke in this context about Broca’s body of work as a whole, noting: “Through her mosaics, Broca looks to glass shards as a means to remind viewers that the traditional paradigms associated with traditional institutions and power dynamics can be broken through and reconstructed into a world that is more healing.”

For more on Broca, visit lilianbroca.com. For more on the exhibit, visit italianculturalcentre.ca.