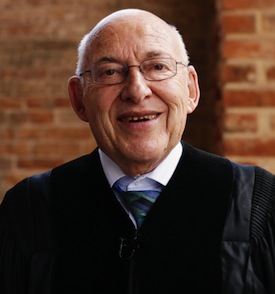

In Petriplatz, Pastor Gregor Hohberg, left, and Imam Kadir Sanci listen as Rabbi Andreas Nachama recites a prayer for peace. (photo by Frithjof Timm)

In the middle of Berlin, on the grounds of where a church was destroyed in the Second World War, a pastor, imam and rabbi are collaborating to create a new reality wherein Christianity, Islam and Judaism can be practised under the same roof.

“It seems so logical that something like this would take place, but it never has before,” said Rabbi Dr. Andreas Nachama who leads the only Reform congregation in Berlin, Sukkat Shalom (House of Peace).

Some congregations and groups of people refrain from intermingling out of fear of losing members to other groups. For Nachama and the other House of One proponents, this is not a concern.

“I think that the congregations are solid and I don’t think that this might turn out to be a problem,” he said. “We have a lot of experience from sharing a building with Catholics, Protestants and Jews, and we’ve never had that kind of problem. The problems we had were very secular and could be solved quickly with a short discussion – things like who is cleaning the toilets after congregation and so on.”

As for the risk of intermarriage, Nachama said intermarriages “take place because people are studying at the same university or classroom, sitting in the same office, or meeting in a restaurant or theatre. I haven’t had a single case where intermarriages originate from a Christian-Jewish dialogue group in all my years.”

The idea for House of One originated five or six years ago with Nachama’s predecessor, Rabbi Tovia Ben Chorin. He was working to bring the concept to life until he retired and moved back to Switzerland. Nachama has been involved with House of One since April 2015.

Nachama is no stranger to Christian, Jewish and Muslim trialogue. He has been involved in the field since 1972, starting at summer camps in western Germany, where a local school invited members of each of the three faiths to discuss common stories and problems.

As Nachama went on to take Jewish studies in university in the 1970s, he also took basic courses on Islam and Catholicism. Gaining a good understanding of these religions has enabled him to effectively introduce his congregation to interfaith interactions since 1999, bringing in his Islamic and Christian counterparts to teach in the synagogue alongside him.

The clergy meet on a regular basis, sometimes involving leaders in their respective communities, but always aiming to keep meetings to no more than 15 people. So, the interfaith groundwork began long before the excavations started in 2007 of Petriplatz, the site of the old church, among other structures, and a new House of God was being planned. The church wanted to build a house where the three religions would each have a holy space of their own.

“Each would have their own synagogue, mosque and church, working together in one building,” said Nachama. “But, everyone would follow his/her own faith tradition, so it was not about some new religion being created.

“Instead, the idea was to build a house of teaching, of worship, wherein the teaching might bring us together; the worship, everyone does for him/herself in his/her religion.

“We can do programs on some aspects of interest to many, like looking at the differences between kosher and halal. We can also offer teaching programs to the general public.”

Worship times do not seem to be an issue either, with the holy day for Muslims being Friday; for Jews, Saturday; and, for Christians, Sunday.

“But, what happens if Christmas Eve is on a Friday night or during Shabbat?” admitted Nachama. “We can always find problems in terms of holy days on the calendar. They will be solved, but it’s not so easy.”

According to Nachama, the most difficult challenge is in the area of politics. “Islam, in particular, is being taken as a hostage for Islamic fundamental brutality,” he said. “That makes it difficult, because those Muslims that we deal with are not part of that. It makes it difficult … in the public eye … to make it understandable that we, as individuals and as congregations here in Berlin, can cooperate and speak with each other, whatever happens.

“My congregation is very much involved in Christian-Jewish dialogue, and we also sometimes have teachings or panel discussions together with Muslims, so it’s not new to my congregation and, as far as I see, the other congregations have had experience in the field before as well.”

As far as reaching beyond congregational circles, Nachama understands all too well that if someone has prejudice, it is he or she who needs to be willing to open their eyes and ears to seeing the other side. “We can’t do it for them,” he said. “If they are willing, we then can try to show them how we see things.”

While the project is gaining momentum and more than a million euros have already been collected, much more is needed to even break ground on the building project.

Nachama anticipates that his congregants will have no problem with the move when the time comes. “We’ve moved already once and, when completed, either parts of the congregation will move or the whole congregation. It won’t be a problem.

“We believe this project is a result of the history in Berlin,” he continued. Given the history of antisemitism in Germany and the Holocaust, people want to create “a new page of history,” he said. “People really try to look for new ways of cooperation, coexistence and respect for other peoples and faiths.”

For more information or to join the project, visit house-of-one.org.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.