It is a master storyteller who can make you feel like you’ve met someone you never knew, visited a city to which you’ve never been, make you long for a people, place and culture you’ve never experienced but from a generation, location and language once, twice or thrice removed. Abraham Karpinowitz (1913-2004) is such a writer. And, thanks to local master storyteller and translator Helen Mintz, more of us can now visit Karpinowitz’s Vilna – a city full of colorful characters, both real and not, and share in a small part of their lives.

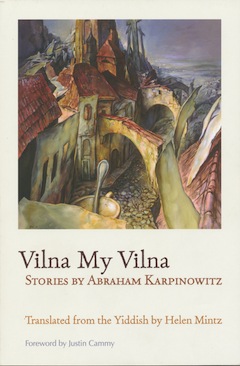

Vilna My Vilna (Syracuse University Press, 2016) is a collection of 13 short stories and two brief memoirs by Karpinowitz, translated from Yiddish into English by Mintz. For context and a better understanding of Karpinowitz and his work – notably one of the main “characters” in his writing, Vilna – there is a foreword by Justin Cammy, an associate professor of Jewish studies and comparative literature at Smith College in Massachusetts, and an introduction by Mintz. These two scholarly essays are invaluable, but if you’re completely unfamiliar with Karpinowitz, perhaps jump ahead and read a few of the stories before heading back to these parts of the book. It’s kind of a Catch-22, in that their insight enhances the enjoyment of the stories, but the stories enhance the understanding of the analysis and history.

Romantics will appreciate most the linked stories of “The Folklorist” and “Chana-Merka the Fishwife.” In the first tale, Rubinshteyn heads to the Vilna fish market to collect material for YIVO (the Yiddish Scientific Institute) because he knows that, if the “genuine language of the people” is not documented, “it would be a great loss for the culture.” Dedicated to his work, and a dedicated bachelor, he fails to notice that Chana-Merka has fallen in love with him and, once his research is complete, he stops visiting the fish market, much to her – and his – sadness. In the second tale, Chana-Merka heads to YIVO herself to make sure that Max Weinreich, its director, knows from whom all of Rubinshteyn’s material came: she makes lists of curses for Weinreich, such as “May you speak so beautifully that only cats understand you,” and “May you be lucky and go crazy in a more important city than Vilna.”

Romantics will appreciate most the linked stories of “The Folklorist” and “Chana-Merka the Fishwife.” In the first tale, Rubinshteyn heads to the Vilna fish market to collect material for YIVO (the Yiddish Scientific Institute) because he knows that, if the “genuine language of the people” is not documented, “it would be a great loss for the culture.” Dedicated to his work, and a dedicated bachelor, he fails to notice that Chana-Merka has fallen in love with him and, once his research is complete, he stops visiting the fish market, much to her – and his – sadness. In the second tale, Chana-Merka heads to YIVO herself to make sure that Max Weinreich, its director, knows from whom all of Rubinshteyn’s material came: she makes lists of curses for Weinreich, such as “May you speak so beautifully that only cats understand you,” and “May you be lucky and go crazy in a more important city than Vilna.”

Weinreich is one of the real people who appear in this collection where fiction and non-fiction meld. Yoysef Giligitsh, a teacher at the Re’al Gymnasium, is another. Most readers will not be able to identify all of these people and, while there will be added realism for those who can, the characters stand on their own. Besides, these people are secondary to the protagonists, who are the fishwives, the prostitutes, the criminals, the poor.

Despite that everyone is trying to eke out an existence, even the criminals follow a moral code. For example, Karpinowitz notes, in “Vilna, Vilna, Our Native City” that the Golden Flag criminal organization’s constitution includes the admonition, “Our members should behave properly and not forget that even though we are who we are, we are still Jews,” and that “[t]here was a directive for the general treasury to provide dowries for poor brides.”

Karpinowitz pokes fun at communism, capitalism, politics in general. His descriptions put readers right into the scene, almost as if they’re standing on the opposite street corner watching events unfold. And he has some wonderful turns of phrase. In “Shibele’s Lottery Ticket,” for example, Sheyndel’s husband goes off to fill the water bucket and never returns: “Sheyndel missed her husband, the shiksa chaser, less than the bucket.”

Or, in one of the two memoirs, “The Tree Beside the Theatre,” Karpinowitz writes about his father’s choice to sell his print shop to run a theatre, “If he’d stayed in the print shop, he’d be a rich man. My mother reminded him of this every time she couldn’t cover expenses. But everything in the print shop, including the machines and the letters, was black, and everything in the theatre was colorful, even the poverty.”

Karpinowitz’s characters have self-dignity and hope. They are not passive, for the most part, but are actively trying to change their situation for the better or to help someone else. Not surprisingly, many of the stories have bleak endings, with the narratives going from charming and/or humorous to horrific, illustrating just how abruptly and brutally this world came to an end.

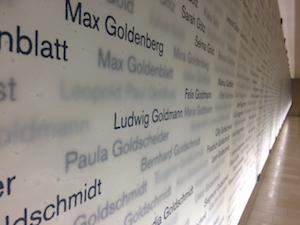

These stories that turn on a dime are so moving. They emphasize just how little people at the time understood that most of them would soon be murdered. As Karpinowitz writes in “Vilna, Vilna, Our Native City”: “For years, a Jew with blue spectacles stood on Daytshe Street begging, ‘Take me across to the other side.’ His plea was so heartrending that, rather than asking to be taken across the few cobblestones separating Gitke Toybe’s Lane from Yiddishe Street, he sounded like he needed to cross a deep and dangerous abyss. Maybe he was the first Jew in Vilna with a premonition about the Holocaust. Just the name of the street, Daytshe Gas, German Street, drove him from one side to the other. We could all see the little water pump and Yoshe’s kvass stall on the other side of the street, but through his dark spectacles, that Jew saw farther. Fate didn’t take him to the safer side. He ended up in the abyss at Ponar with everyone else.”

Karpinowitz survived the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, having left Vilna in 1937. He briefly returned in 1944 and then, after two years in a displaced persons camp in Cyprus, moved to Israel. Mintz notes that he wrote seven works of fiction, two biographies, a play and five short story collections. He was awarded the Manger Prize (1981), among several other honors.

In the stories of Vilna My Vilna, the geography of the city is integral, and the maps included are useful in situating the action. The glossary is also an essential part of the book: kvass, for example, is a “fermented beverage made from black or regular rye bread.”

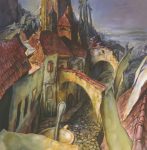

Adding even more value to this collection are three illustrations by Yosl Bergner that were in the original 1967 Yiddish publication of Karpinowitz’s Baym Vilner durkhhoyf and the painting “Soutine Street” by Samuel Bak is the cover of Vilna My Vilna. Both artists (and the Pucker Gallery, in the case of Bak’s painting) gave permission for their work to be used at no charge, which is an indication of the translation’s import beyond entertainment.

Mintz’s acknowledgements are many, and that she accepted so much input into the book speaks volumes about her integrity and the quality of her work. “Translating these stories brought me great joy,” she writes. “While never swerving from the truth, Abraham Karpinowitz answered genocide with love: love for his characters and love for his craft as a writer.” With Vilna My Vilna, Mintz adds her love, and that of many others, to ensure that Vilna, its people and its stories will not be forgotten.

The two stories, solving his father’s murder and getting to the bottom (and the top) of Malina, are interspersed narratives that keep you guessing and entertained. Along the way, the reader encounters a Chassidic un-kosher kidnapping that goes awry (imagine the Marx brothers in black hats) and a bris (kosher or not depending on whether you are Orthodox or Reform) that are grist for Leviant’s mill of linguistic tomfoolery. You meet other academics, letting you in on university rivalries and gossip. Believe it or not, but a cookie with an incredible miniature topping in a Vienna café is an important character in the plot development that might have been written by Kafka, Borges or Nabokov, but it is pure Leviant, plying his considerable art as a fabulist.

The two stories, solving his father’s murder and getting to the bottom (and the top) of Malina, are interspersed narratives that keep you guessing and entertained. Along the way, the reader encounters a Chassidic un-kosher kidnapping that goes awry (imagine the Marx brothers in black hats) and a bris (kosher or not depending on whether you are Orthodox or Reform) that are grist for Leviant’s mill of linguistic tomfoolery. You meet other academics, letting you in on university rivalries and gossip. Believe it or not, but a cookie with an incredible miniature topping in a Vienna café is an important character in the plot development that might have been written by Kafka, Borges or Nabokov, but it is pure Leviant, plying his considerable art as a fabulist.