Let’s say it at the outset: this book is a gem. Every page of The Story of Hebrew by Lewis Glinert (Princeton University Press, 2017) is packed with information about the language, from its beginnings through post-1948 Israel. In addition to this longitudinal approach, Glinert, a professor of Hebrew and linguistics at Dartmouth, also approaches his subject laterally, focusing on various lands where Jewish/Hebrew life and culture thrived, like early Palestine, Babylonia, North Africa, Spain, Europe and Russia, the United States and Israel.

The book shows us how living under Greek and Roman domination affected Hebrew and how vocabulary from those occupiers seeped into the language. Two examples, the first mine, the second Glinert’s: the simple word for shoemaker in Hebrew, sandlar, which comes from the Latin sandalrius; and Sanhedrin, the Jewish High Court, which stems from the Greek synedrion. Jews did not shy away from these foreign influences; their Hebrew language embraced them.

Glinert also traces the changes in the use of the language from biblical times through the Mishnah (before and after 200 CE), where the Hebrew of that period was more direct and seemingly more colloquial, as can be seen by comparing a text from the Mishnah with any chapter in the Bible. During the next two or three hundred years, written Hebrew then moved on from the Hebrew-only Mishnah to the two-language Talmud, with its mix of mostly Aramaic and much less Hebrew. (In all of this, of course, we only have written texts to go by.)

Glinert also traces the changes in the use of the language from biblical times through the Mishnah (before and after 200 CE), where the Hebrew of that period was more direct and seemingly more colloquial, as can be seen by comparing a text from the Mishnah with any chapter in the Bible. During the next two or three hundred years, written Hebrew then moved on from the Hebrew-only Mishnah to the two-language Talmud, with its mix of mostly Aramaic and much less Hebrew. (In all of this, of course, we only have written texts to go by.)

With sacred books passing from generation to generation orally, correct pronunciation might be lost or distorted. Along came the Masoretes (from the Hebrew word, masorah, tradition), who, by the year 1000, had created above- and below-the-letters signs that ingeniously indicated pronunciation, melody, accent and phrasing.

Jews also contributed to scientific learning by writing about medicine in Hebrew. I am sure it will surprise many readers, as it did me, that in Italy’s first medical school, in Salerno, founded in the ninth century, the languages of instruction were Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Arabic. And, in southern France, in Arles, Narbonne and Montpellier, the official language of instruction in these medical schools was Hebrew.

Religious attitude also influenced how Hebrew was used. Glinert delves into this divide by showing that, during the 11th and 12th centuries in Ashkenaz (in northern France and the Rhineland), the accent was on liturgy and Torah scholarship – the works of Rashi, for instance – while in Sepharad (Spain) and Italy secular Hebrew poetry flourished, influenced by Arabic poetry, exemplified by Yehuda Halevi and other poets.

The book devotes two remarkable chapters to the interaction of Christians with Hebrew.

In one of these unholy intersections, two of the noted translators of the Bible from Hebrew, the church father Jerome (fourth century) and Martin Luther (1534), respected Hebrew but disparaged Jews and Judaism. In his notorious 1542 book On the Jews and Their Lies, Luther asserts, “Jews should be expelled before they poison more wells and ritually abuse more children.”

A better relationship ensued with English translators. William Tyndale was the first to render the Five Books of Moses (1530) into English directly from the Hebrew. In so doing, he defied a bishop’s ban on a translation other than the Latin Vulgate. Tyndale’s translation led to the classic 1611 King James version of the complete Bible, whose English rhythms, cadences and even sentence structure enormously affected English.

As Glinert elegantly puts it: these two translations would “inject a Hebraic quality into the syntax and phraseology of English literary usage without parallel in any other European culture.” The author further adds that echoes of this biblical English can be seen from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass poetry collection to Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Hebrew also made its mark in the early history of the United States. The Pilgrims saw themselves as the New Israelites, giving their towns name like New Canaan and Salem – even their Thanksgiving was a belated Sukkot to celebrate a bountiful harvest. And Hebrew was at one time ensconced as a mandatory subject in the Ivy League colleges. I recently read that at graduation ceremonies students would deliver orations in Hebrew, Greek and Latin, and university presidents, like Ezra Stiles of Yale, would also occasionally give their commencement talks in Hebrew.

Glinert writes that the door to modernity in Europe was opened in 1780 by two books published on different sides of Europe. One, in Germany, was Moses Mendelssohn’s Biur, the first volume of his translation of the Torah into German; the other, in a small town in the Ukraine, was a book in Hebrew about Chassidic thought.

Slowly, from the advent of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment movement, through newspapers, magazines and books, modern Hebrew was being reshaped, culminating with Jews resettling Palestine in the late 19th century, along with Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s call, at the turn of the 20th century, for Jews to speak only Hebrew. Glinert shows us how the thrust for Hebraization continued once the British got the Mandate for Palestine in 1922 from the League of Nations. They recognized Hebrew as the language of instruction for public schools, broadcasting, the courts and civil regulations. With the founding of the state of Israel in 1948 and mass immigration, Hebrew – which throughout the centuries had always been read, studied and written, and only occasionally spoken – reached its efflorescence.

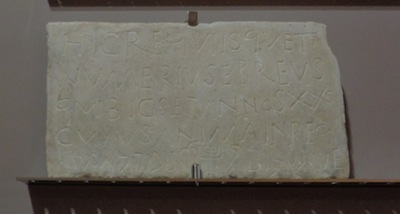

The Story of Hebrew is a superb book, meticulously researched and beautifully written. Two of my favourites among the many text-enhancing illustrations and photographs are a photo of a page from one of Sir Isaac Newton’s notebooks, where he has a phrase in Hebrew written in his neat printed script; and a page from Franz Kafka’s Hebrew notebook, with two columns of nicely calligraphed Hebrew words on one side with their German translation (in longhand) on the other.

Read this marvelous study – perhaps, if you don’t know Hebrew, it will inspire you to learn it and become part of a more than 3,000-year tradition of transmission.

Curt Leviant’s most recent books are the novels King of Yiddish and Kafka’s Son.

The engineers also had to lower the risk of the system getting blocked. They realized that water pipes that ran along the side of a mountain would be hard to clean. Thus, they designed special water filters. These filters made it easy to trap and remove rocks or silt. If there were particles, they would settle in the reservoirs, not in the pipes. The engineers’ design was practical. It functioned throughout the year and, importantly, provided for a lot of water storage. It included crisscrossing water pipelines, channels, dams, tunnels, reservoirs and cisterns (totaling some 200 surface and underground units).

The engineers also had to lower the risk of the system getting blocked. They realized that water pipes that ran along the side of a mountain would be hard to clean. Thus, they designed special water filters. These filters made it easy to trap and remove rocks or silt. If there were particles, they would settle in the reservoirs, not in the pipes. The engineers’ design was practical. It functioned throughout the year and, importantly, provided for a lot of water storage. It included crisscrossing water pipelines, channels, dams, tunnels, reservoirs and cisterns (totaling some 200 surface and underground units).