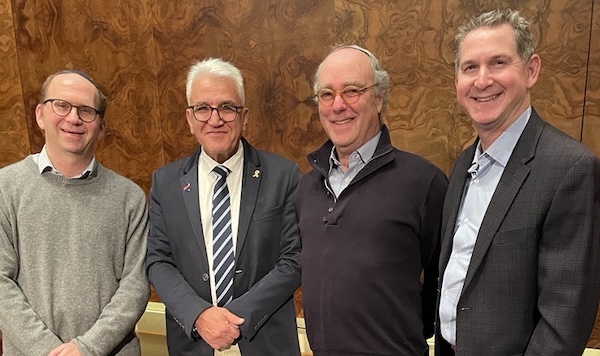

Left to right are Rabbi Jonathan Infeld, Dr. Salman Zarka, Dr. Tim Oberlander and Dr. Erik Swartz at Congregation Beth Israel, where Zarka gave a few talks Nov. 21-23. (photo from Beth Israel)

“Our professional ethics, as well as Israeli legislation, mandate that we provide life-saving medical care to anyone in need. We do so for all citizens in Israel without discrimination based on religion, origin, race or political beliefs. We provided this care for Syrians and previously treated Lebanese patients, until the border was closed in 2000,” Dr. Salman Zarka, director of Ziv Medical Centre, told the Independent.

Zarka was in Vancouver last week, speaking at Congregation Beth Israel on the ethics of triage, on treating Syrian patients in Israel, and about his community, the Druze.

“I am delighted to visit Canada and share with different audiences the amazing work we’ve been doing at Ziv Medical Centre this past year, dealing with both war and emergency situations,” Zarka told the Independent. “This visit is also a great chance to thank the supporters in Canada from the Jewish community, Beth Israel, the Federation and the Ronald S. Roadburg Foundation.

“The visit is a chance to share our ongoing efforts in treating the wounded, as well as past activities related to caring for Syrian casualties,” he said.

Caring for an “enemy”

“The humanitarian aid to Syrians lasted for around five years, from 2013 to 2018, until [Bashar al-]Assad took back control of southern Syria, closed the border, thereby stopping patients and wounded from Syria coming to Israel,” said Zarka, who led the establishment of the now-closed military field hospital that provided medical support to Syrians wounded in the country’s ongoing civil war. He and his colleagues at Ziv Medical Centre have also provided care to Syrians.

“It is indeed unusual and uncommon to extend a professional and human hand to your enemies during their time of need,” he said. “On the other hand, we have an ethical duty to treat every patient and every wounded person. This dilemma existed at the start of the process, when wounded Syrians arrived at the Israel-Syria border. We treated them and asked ourselves what we should do next. On one hand, the Syrians are one of our most severe enemies, yet our ethics and professional standards oblige us to save lives and provide aid to all in need. Moreover, Israel is known for its global humanitarian assistance. Ultimately, we chose to provide care, treating close to 4,600 Syrians, including children, women and men.”

Before he retired from the military, Zarka served in various capacities in the Israel Defence Forces, including many leadership roles, and is currently a colonel brigadier in the reserve force. He is an expert in public health and public health administration, as well as being a practising physician, among other things. He was Israel’s chief COVID officer during the pandemic. In 2014, he became the director at Ziv Medical Centre, in Tzfat, about 11 kilometres from Israel’s border with Lebanon.

“Ziv Medical Centre employs about 2,200 staff members who come from the unique multicultural background of the region,” said Zarka. “At Ziv, secular Jews work alongside ultra-Orthodox Jews, Muslims, Christians, Druze, Circassians and Bedouins,” he said. “The hospital atmosphere is familial, and everyone collaborates to achieve the noble goals of saving lives and bringing healing to those in need. Cultural differences influence how people perceive illness, and our multicultural staff enables us to offer culturally sensitive care for various health needs.”

After the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attacks on southern Israel, the northern part of the country faced increased threats from Hezbollah in Lebanon, leading to mass evacuations of the region.

“For over a year now, the north has faced a complex situation with rocket fire and evacuations,” said Zarka. “This state of conflict forces Ziv Medical Centre to operate from protected spaces and remain prepared for mass casualty incidents. The need for readiness and staying in protected areas limits our ability to treat patients comprehensively, but it is unethical to deny necessary medical treatment to our northern population, which depends on Ziv for their routine treatment.”

The challenges are numerous.

“Some of our patients left the area, preventing us from continuing their care, while others relocated nearby and continued their treatment,” Zarka said. “Both the evacuated population and those facing rocket fire, injury and loss require increased mental health support, leading to a rise in emergency room visits. Additionally, some of our staff had to evacuate from their homes, posing challenges for employees who continued to work at Ziv despite the distance.”

The security situation in the north requires the medical centre to reassess its reinforced spaces, while continuing to provide necessary medical care to patients, even during emergencies, said Zarka.

“The end of the war and the return of residents to their homes will pose significant mental health challenges for both adults and youth, as was seen following the COVID-19 pandemic,” he added. “Preparing to expand services in the region is essential. The north will require substantial investment not only for recovery but for growth, making it a beautiful and unique area, home to multicultural residents, many of whom are from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who depend on Ziv Medical Centre for their health care.”

Israel’s Druze community

There are about 150,000 Israeli Druze. The Druze religion is monotheistic; it branched off from Shia Islam in the 11th century and has since incorporated elements of other religions. The Druze are ethnically and linguistically Arabic, mainly living in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel, notably, in northern Israel.

“The Druze community in Israel chose, even prior to the state’s establishment (back in the 1930s), to ally with the Jewish population, a minority at the time, possibly as a bond between minorities,” explained Zarka. “The Druze supported the Jews before the state was founded and fought in the War of Independence. Afterward, the Druze decided to enlist in the IDF as volunteers and requested mandatory enlistment for their men, which began in 1956. Druze men serve in the IDF like Jewish men, with high enlistment rates in combat units, continuing with a significant service, achieving senior ranks. I served in the IDF for over 25 years in key roles in the Medical Corps, commander of medical services in the Northern Command and head of medical services, retiring with the rank of colonel.”

A 2023 article in the National Post noted, “Aside from combat roles, the Druze have a presence in health care: in 2011, the Druze made up 16% of the IDF’s medics, despite making up only 1.6% of the force.” The article gave Zarka as an example of a prominent Druze, having achieved success in both the military and in health care.

There are challenges for the Druze community in Israel, however.

“Much has been said about the ‘blood pact’ forged between the Druze and the Jews in Israel, which, unfortunately, translates into casualties in Israel’s various military conflicts,” Zarka told the Independent. “Alongside this connection, particularly strong in the IDF and security forces, there exists a civilian gap in the so-called ‘pact of life.’ The Nation-State Law [in 2018] did not address minorities in Israel, omitting the crucial term ‘equality,’ making the Druze feel relegated to a lesser status compared to their Jewish fellow citizens.

“Beyond the significance of this matter, which is not merely declarative, Druze towns (mainly villages) have long suffered from planning and land allocation issues, complicating construction and housing, even for discharged IDF soldiers. Addressing these two issues, namely equality and long-term planning, is central to the relationship between the Druze and the government.”