Charlotte Schallié, a University of Victoria scholar and Holocaust historian who is leading the graphic novel project, with survivor David Schaffer and graphic artist Miriam Libicki, left, at Schaffer’s home in Vancouver in January 2020. (photo by Mike Morash)

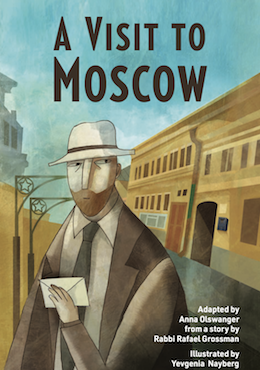

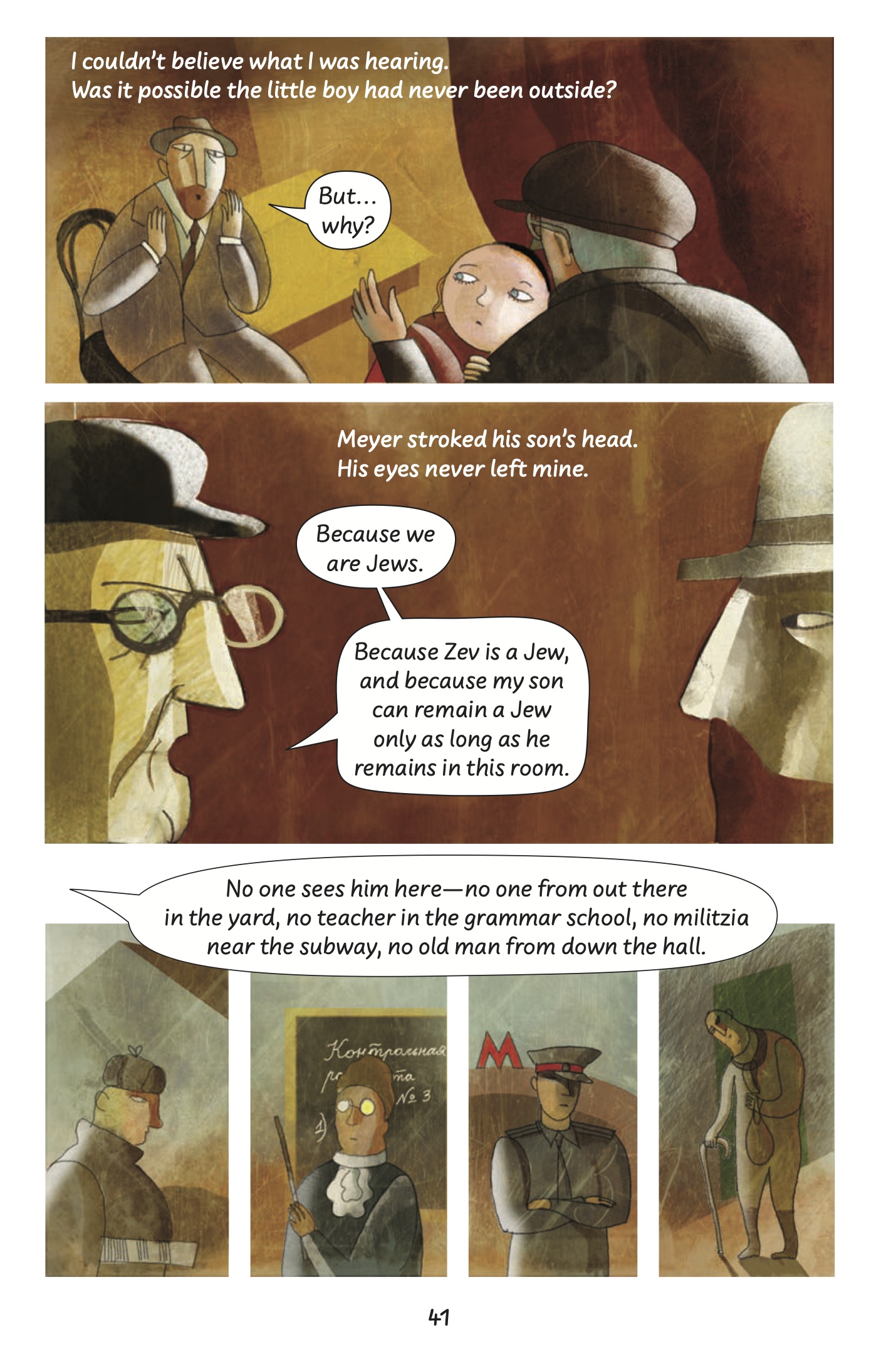

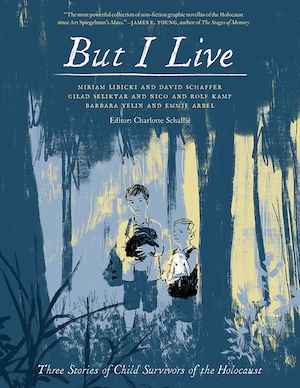

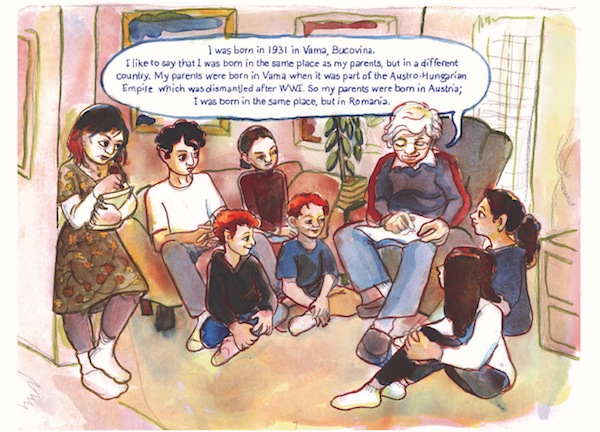

A University of Victoria project, first announced in January 2020, came to fruition this spring with the release of But I Live, a graphic novel that tells the stories of four Holocaust survivors.

But I Live involved an international team of researchers, students and institutional partners from three continents, and brought together four survivors and three graphic artists to create an autobiographic series recounting one of the darkest periods in human history. The survivors who told their stories were Emmie Arbel (Israel), Nico and Rolf Kamp (Holland) and David Schaffer (Canada). Their stories were transformed into art by Barbara Yelin (Germany), Gilad Seliktar (Israel) and Miriam Libicki (Canada). The project was edited and organized by Charlotte Schallié, chair of the department of Germanic Slavic studies at UVic and head of Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education at the university.

“Many people in North America have learned about the history of the Holocaust through survivor stories that are repeated in popular culture, which largely focus on survival in the concentration camps or experiences of hiding in Nazi-occupied territory,” said Schallié. “The three stories in But I Live complicate these mainstream narratives by exploring complex topics such as the burden of memory, the need to testify, the ripple effects of trauma and the impact of the Holocaust on descendants of survivors, for example. As historical documents, they are also important for centring the survivors’ experiences and enabling them to tell their own stories.”

Though the gravity of the crimes committed during the Holocaust is well documented, the majority of visual records were largely produced by the Nazis and their collaborators. “These are important historical sources,” said Schallié, “but a sole focus on documentation produced by perpetrators ignores the value of survivors as living knowledge-keepers.”

An objective of the project, therefore, was to turn the perspective over to the survivors. “A survivor-centred approach to gathering testimony about the Holocaust honours the integrity and humanity of the person’s lived experience, while respecting their right to tell their own story,” Schallié said.

Another consideration in the project was time – the majority of Holocaust survivors alive today were young children during the war and are now in their 80s and 90s. The importance of learning from these knowledge-keepers is increasingly vital.

“If we don’t engage them in our research now, their expertise and experience will soon be lost,” Schallié stressed.

There is, in her view, a moral obligation and duty to collect and preserve survivor testimonies. “Each voice that was marked to be silenced by the perpetrators of these atrocities matters greatly and needs to be heard and acknowledged,” she said.

An additional goal of But I Live is to interest young readers in Canada, where high schools are not mandated to include the study of the Holocaust in their curricula.

“We hope that our visual storytelling work will appeal to youths and young adult readers, and elicit within them a deep sense of empathy that leads them to think critically about the historical past and present,” said Schaille.

“Holocaust survivor stories that are presented as heroic narratives, where the storyline progresses from dark to light – or from a site of danger to one of safety – place a heavy burden and responsibility on survivors, whose life stories and memories are unlikely to conform to that model, and simplifies the reality of their lived experiences. But I Live holds space for fragmented memories, difficult emotions and the afterlife of trauma. In doing so, it complicates mainstream tropes, clichés and iconographic imagery that is sometimes misappropriated or exploited in popular culture,” she explained.

The work at UVic expands on previous projects, such as the book On Listening to Holocaust Survivors: Beyond Testimony by Henry Greenspan of the University of Michigan, which focuses on survivor accounts while being mindful of the trauma such memories can evoke.

“Eliciting experiences and memories of extreme human suffering from the survivors necessitated a research process and practice that privileged their safety by minimizing the risk of re-traumatization, managing potential triggers and providing sustained support for all participating project partners,” Schallié said. “This approach ensured that we – the stewards of survivor memories – honoured what we felt was our obligation and duty to amplify the voices of the Holocaust survivors.”

But I Live was released by New Jewish Press, a division of University of Toronto Press. A German edition, Aber ich lebe, was published by C.H. Beck in July and has received positive coverage in the German broadsheets Der Tagesspiegel and Die Zeit. In November, the book received a German LUCHS-Preis for literature.

On Oct. 23, But I Live won the 2022 Canadian Jewish Literary Award for biography, presented at York University in Toronto. At the ceremony, the project was lauded for exemplifying “the power of the non-fiction graphic novel to convey the experience and aftereffects of the Shoah.… The historical essays, an illustrated postscript from the artists and personal words from each of the survivors offer a profound meditation on the past and its reach into the present.”

But I Live will be featured at the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival here in Vancouver on Feb. 12.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.