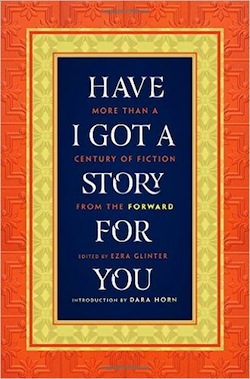

It must have been a prodigious effort by editor Ezra Glinter to look through countless Yiddish Forward microfilms going back more than 100 years and come up with the superb collection of short fiction Have I Got a Story for You: More than a Century of Fiction from the Forward (W.W. Norton, 2016).

Unlike contemporary American newspapers, Yiddish papers, both here and in Europe, published fiction. Readers looked forward to the weekend editions, where they could find stories by their old favourite authors and newly emerging writers.

This new variegated collection, which begins with 1907 and ends in 2015, with contributions by 20 talented translators, including Glinter, has many of the famous names in 20th-century Yiddish belles lettres – Sholem Asch, David Bergelson, Avraham Reyzen, Israel Joshua Singer, Isaac Bashevis Singer and Chaim Grade. And, though even the lesser-known names were familiar for decades to the loyal Forward audience, they may not be so anymore, and the volume contains cogent and insightful introductions to each writer.

Have I Got a Story for You is a beautifully produced book, from the stunning, colourful cover, the fine introductions by Glinter and novelist Dara Horn and, of course, the lively fiction. Even the clever title, Have I Got a Story for You, resonates with Yiddish braggadocio.

Have I Got a Story for You is a beautifully produced book, from the stunning, colourful cover, the fine introductions by Glinter and novelist Dara Horn and, of course, the lively fiction. Even the clever title, Have I Got a Story for You, resonates with Yiddish braggadocio.

The anthology begins with a story by Rokhl Brokhes, Golde’s Lament, published in 1907, about a woman who is tormented with jealousy because her husband has sailed to America with another woman posing as his wife, and concludes with a 2015 story, Studies in Solfege, by the current Yiddish Forward editor, Boris Sandler, about which I’ll tell you later.

First, we read stories about the immigrant experience, including one by Abe Cahan himself, the guiding spirit of the Forward (known in Yiddish as the Forverts) from 1903 to 1946, and humorous sketches by B. Kovner, who wrote for the paper for nearly 70 years of his 100-year life (1874-1974).

Some of the book’s most powerful pages, whose sheer force of imaginative and vivid prose overwhelms the reader, were written in Russia under wartime circumstances. Here we see gripping stories by Asch, Bergelson and I.J. Singer. Obviously, tales with such stress and suspense make New York-based fiction about collecting rent or about a lovelorn seamstress pale by comparison.

It is also noteworthy that, whereas stories by Yiddish masters like Peretz, Sholem Aleichem and Reyzen invariably pertained to Jewish life, in this collection, Yiddishkeit is at a minimum. One story by the very secular daughter of Aleichem, Lyala Kaufman, speaks of a woman who prays daily but doesn’t particularly like her assimilated son and daughter-in-law. She closes her morning prayer with a wish that “they die a horrible death.” Another story, by Zalman Schneour, tells of a little youngster who is tempted and finally succumbs to tasting pig meat.

In their Eastern European shtetls or cities, the rhythms of Jewish life were central to Jews’ existence. In the United States, with many of the early immigrants not committed to Jewish observance, the secularly minded Yiddish writers writing for a socialist-leaning paper like the Forward did not have Yiddishkeit at the forefront of their creative imagination.

Noteworthy, too, is that not one of the writers included in Have I Got a Story for You was born in the United States. One can understand that, early in the 20th century, the Yiddish writers would be European-born, but, as the decades progressed toward the mid-20th century, one would have expected at least one American-born Yiddish writer to emerge. But none did.

Also, if you look at the years of birth of the contributing writers, only one was born in the 1920s and none was born in the 1930s or 1940s. The two writers who were born in the early 1950s were Russians. This means that most of the writers who contributed to the Forward, at least those selected for this anthology, were born prior to 1910.

In A Treasury of Yiddish Stories (1953), edited by Irving Howe and Eliezer Greenberg, Grade, born in 1910, was the youngest author. And so it is curious to see in this anthology, published in 2016 – 53 years later – that Grade is still among the youngest. There are only three younger than he, Yente Mash (1922), Mikhoel Felsenbaum (1951) and Sandler (1950). Certainly the decimation of Jewry during the Holocaust and the repressive Stalinist regime in Russia had something to do with this gap.

(I should add, if only parenthetically, that in the magazine Afn Shvel, published by the League for Yiddish, one can read American-born Yiddish writers, in their 20s and 30s, publishing fiction and non-fiction.)

Full of Yiddishkeit, however, is the masterful novella by Grade, Grandfathers and Grandchildren. Set in an old Vilna shul between the two world wars, it tells of a group of old men whose children have assimilated. Their lives perk up when little boys come into the shul in the winter to warm up, and the old men start giving them private lessons. During summer, the boys disappear but their lives take on new meaning again when two yeshivah bokhers come into the shul to look for old texts and take on the oldsters as their students.

The last two stories in the anthology are by Russian Yiddish writers. Felsenbaum, now living in Israel, depicts a married Israeli Yiddish writer who goes to a Basel book fair, where he meets and falls in love with a beautiful woman. In the book’s last tale, Sandler focuses on a teenage boy who describes taking singing lessons from a slightly older girl; she also introduces him to the Indian love guidebook, Kama Sutra.

I have resisted quoting delectable lines from this anthology till now, but can resist no longer. When the girl asks the boy if he knows what Kama Sutra is, he says the first thing that comes into his head: “Of course. It’s a type of Japanese wrestling.”

Curt Leviant is the author of two recent novels, King of Yiddish and Kafka’s Son.