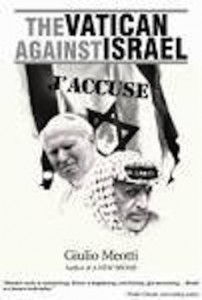

The Catholic Church did not initiate diplomatic relations with the state of Israel until 1993 and, according to the Italian writer Giulio Meotti, things haven’t been all rainbows since then either.

The creation of a thriving Jewish state creates a theological conundrum for the Catholic Church, Meotti writes in The Vatican Against Israel: J’Accuse (Mantua Books, 2013), because it is a refutation of the theological view that Judaism should wither and die in the shadow of a successor religion, Christianity. The theological imperative of Jewish disappearance is now accompanied, he writes, by a geopolitical imperative that Israel should vanish.

The creation of a thriving Jewish state creates a theological conundrum for the Catholic Church, Meotti writes in The Vatican Against Israel: J’Accuse (Mantua Books, 2013), because it is a refutation of the theological view that Judaism should wither and die in the shadow of a successor religion, Christianity. The theological imperative of Jewish disappearance is now accompanied, he writes, by a geopolitical imperative that Israel should vanish.

“Replacement theology stated that Christians had inherited the covenant and replaced the Jews as the Chosen People. The concept of replacement geography similarly replaces the historical connection of one people to the land with a connection between another people and the land,” Meotti writes. “The existence of a restored Israel in the land of the Bible, proof that the Jewish people is not annihilated, assimilated and withering away, is the living refutation of the Christian myth about the Jewish end in the historical process.”

The necessity of rejecting Zionism and, in its time, Israel, bested even the liberalizing influence of the Second Vatican Council, the near-revolutionary reconsideration that took place within Catholicism in the early 1960s. This period, which saw the Church recognize Judaism and Christianity as familial theologies and renounce the millennia-old deicide charge against the Jews, nevertheless has a stream that abhors Zionism. Meotti writes that two conflicting Vatican tendencies developed at that time and still dominate: “theological dialogue with Judaism, and political support for the Arabs.” (The gushing lamentation offered by the Vatican on the death of Yasser Arafat is particularly striking.)

Meotti contends that this process has involved the Catholic Church differentiating between “good” and “docile” Jews of the Diaspora and the “bad” and “arrogant” Jews of Israel.

The book is a litany of indictments. The Church had relations with the PLO before it had relations with Israel. Top Church leaders have repeatedly accused Israel of behaving like Nazis. They routinely use crucifixion motifs in the Israeli-Palestinian context, with Jews playing the Romans and Palestinians, of course, playing the beatific victim. Israel, said one archbishop, was imposing “the sufferings of the passion of Jesus on the Arab Christians.” Another, at the time of the Palestinians’ seizure of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, declared: “Our Palestinian people in Bethlehem died like a crucified martyr.” Arafat himself jumped on the bandwagon, declaring: “Jesus Christ was the first Palestinian fedayeen who carried his sword along the road on which today the Palestinians carry their cross.”

The first translation into Arabic of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion was courtesy of the Catholic Church. One archbishop was convicted of using his immunity to smuggle explosives to Palestinian terrorists and served just four years of his 12-year term after intervention by the Pope and a promise to make no more trouble. (He turned up again in 2010 on the fatal “Freedom Flotilla” that sought to bring aid to Hamas terrorists and has goaded Palestinian Christians to violence, insisting it is the only thing that will move Israelis.) Today, Catholic-affiliated nongovernmental organizations are among the leaders in the anti-Israel boycott, divestment and sanctions movement.

The Vatican’s relationship to the Holocaust is particularly dissolute. Pope John Paul II, in 1979, spoke at Auschwitz, noting that “six million Poles lost their lives during the Second World War, one-fifth of the nation,” failing to note that these were almost all Jews. Instead, he called Auschwitz “the Golgotha of the contemporary world,” Golgotha being the place in Jerusalem where Jesus is said to have been crucified.

More perversely, after visiting Mauthausen, the Pope said that the Jews “enriched the world by their suffering,” He seemed to be echoing the thoughts of John Cardinal O’Connor, then archbishop of New York, who a year earlier had visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum, and asserted that “the Holocaust is an enormous gift that Judaism has given to the world.”

John Paul also infuriated Jews, among others, by conferring a papal knighthood on Kurt Waldheim, the former Austrian president, United Nations secretary-general and Nazi war criminal.

When Jews objected to a proposal to build a Carmelite convent at Auschwitz, the mother superior of the order asked: “Why do the Jews want special treatment in Auschwitz only for themselves? Do they still consider themselves the Chosen People?”

The “J’Accuse” part, which channels the moral outrage of Emile Zola, is fair enough, but this book is only partly about the Vatican. Meotti dredges up equally egregious affronts perpetrated by countless other Christian denominations.

The book is a searing indictment of the Catholic Church, but it is also deeply flawed. At the least, the title is deceptive. The “J’Accuse” part, which channels the moral outrage of Emile Zola, is fair enough, but this book is only partly about the Vatican. Meotti dredges up equally egregious affronts perpetrated by countless other Christian denominations. By no means is Meotti’s condemnation limited to the Vatican, and it is difficult to discern why the title should suggest it is.

Meotti frequently puts uncited statements in quotations. For example, during the 1967 war, when Israel faced annihilation from the Arab states, Meotti claims the Vatican gave the order: “Cheer for the other side.” The quote marks suggest someone literally said this, but whom? On another occasion, he attributes, in quotes, the statement “Jerusalem must be Judenrein.” But who is alleged to have said it? One can also frequently sense comments being stretched out of context to fit the thesis.

Too many times to count, Meotti declares one Christian assertion or another “a blood libel.” The term’s over-usage diminishes whatever power the accusation carries. And nowhere is his over-usage more disturbing than in his casual, often flippant invocation of Nazism.

He writes, “Like Hitlerism, Palestinianism is not a national identity, but a criminal ideological construct…. Worse, the Netanya Passover bombing that killed 30 is a “mini Holocaust.” And, “The dark irony is that the Europeans who are supporting the Palestinians’ ‘right of return’ are living in homes stolen from Jews they helped to gas.”

Meotti’s book has the potential to make an important case against Christian antisemitism and anti-Zionism. While it doesn’t fail completely – the evidence being compendious – the charge to the jury is so overwrought that one feels resentful at being manipulated. The facts would speak for themselves if the author would step back a bit.

Pat Johnson is a Vancouver writer and principal in PRsuasiveMedia.com.