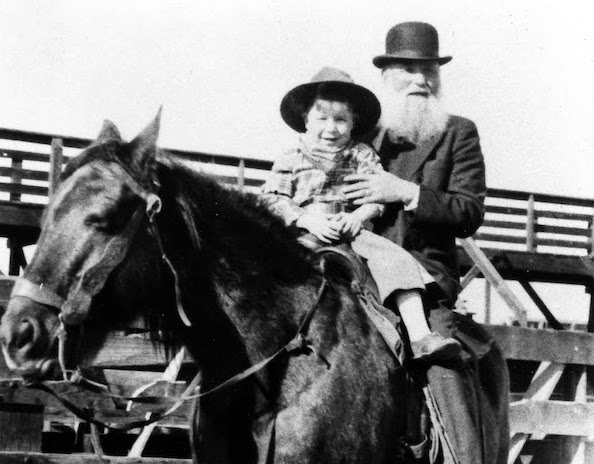

Max Czollek, left, speaks with Prof. Chris Friedrichs, after Czollek launched his new book here Jan. 19. (photo by Pat Johnson)

German attempts to create a cohesive national narrative into which newcomers must integrate is a mistake – and the role Jewish Germans play in this “Theatre of Memory” is especially problematic, according to Max Czollek, a provocative thinker who was hosted by the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival last month.

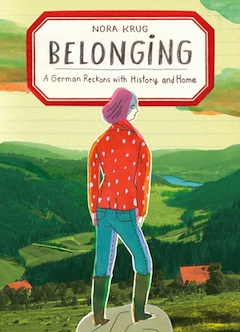

Czollek visited Vancouver Jan. 19, the only Canadian stop on a North American tour promoting the English translation of his book De-integrate: A Jewish Survival Guide for the 21st Century. He excoriated the German integration process as an ideological disaster.

“The only integration Germany has done well is the integration of old Nazis,” he said, explaining that about 99% of Nazi core perpetrators never met justice and, in fact, often succeeded in postwar Germany despite their wartime activities. By contrast, he notes in his book, those who challenged the Nazi regime were often viewed in the postwar context as politically untrustworthy: “[A]fter all, they had already revealed themselves as willing to resist the structures of the German state before.”

While the failure of the larger integration scheme is a theme of Czollek’s book, his main thesis is that Jews are being used to cover up the atrocities of the past. In the contemporary German narrative of integration, newcomers to the country are expected to assimilate into a vaguely defined “guiding culture” (Leitkultur) and not misbehave, Czollek told an audience in the Zack Gallery. But, despite that the vast majority of German Jews are migrants, too, that expectation is not imposed on them. Instead, Jewish Germans are assigned a different and unique role in a German narrative that seeks a return to a normality that was shattered by the Nazi era.

Positioning German Jews collectively as bit players in a larger narrative of redemption reduces them to a cover for the history of their own destruction, he argued: “Because, as long as there are Jews in Germany, then Germans can’t be Nazis.” He later said, “We don’t feel this is our function – making Germans feel good again.”

Czollek, who was born in East Berlin in 1987, two years before the reunification of Germany, explained the different postwar experiences of the tiny Jewish populations of East Germany and West Germany. Numerically, though, these experiences are overwhelmed by those of post-Soviet Jews: 90% of German Jews are migrants from the former Soviet Union or their descendants, he said. And these migrants (or, in the term used for their children and grandchildren, “postmigrants”) are excluded from the burdens placed on other newcomers, especially Muslims. In fact, said Czollek, Muslim immigrants play a role in this narrative, too, in which “good Germans” must now protect Jews against perceived threats from Muslims.

The author looks with a particularly jaundiced eye at German Jews who subscribe to this narrative, such as those who vote for the far-right Alternative for Germany party (AfD) based on anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant policies. “Maybe the next time the mosques are going to burn first, but then the synagogues are going to be next,” Czollek said. “We know if the Muslims won’t be able to live safe in Germany, then the Jews won’t either.”

The author looks with a particularly jaundiced eye at German Jews who subscribe to this narrative, such as those who vote for the far-right Alternative for Germany party (AfD) based on anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant policies. “Maybe the next time the mosques are going to burn first, but then the synagogues are going to be next,” Czollek said. “We know if the Muslims won’t be able to live safe in Germany, then the Jews won’t either.”

The very idea of a German “guiding culture” is flawed, Czollek argues, not only because the unification of Germany in the 19th century brought together diverse tribes and groupings into what is now purveyed as a unitary nation, but because the postwar immigration of diverse peoples has made such a unified culture unworkable. “Because, given its current state of social diversity, arriving at an ethnically and culturally homogeneous Germany would simply require ethnic and cultural cleansing,” Czollek writes.

A central flaw in the integration narrative, he argues, is that, no matter how long someone named Mohammad has lived in Germany, they will be subject to different criteria of good citizenship. Neo-Nazis who commit arson against refugee shelters or march down the street chanting “Heil Hitler” are not accused of failing to integrate into the German culture, he noted.

“[A]t what point are you no longer considered an immigrant who refuses to integrate [Integrationsverweigerer], but simply a frustrated German?” he asks.

Czollek contends that the narrative of a prevailing German culture (and integration into it) has seeped from the far-right across the spectrum. “Not a single democratic party platform neglects to centre this term in discussions of social belonging,” he writes. “No discussion panels about migration are complete without someone underscoring the importance of integration.”

Czollek argues for a live-and-let-live approach, but suggests the advocates of integration aren’t interested.

“They can eat weisswurst with sweet mustard for lunch and drink at least one litre of beer a day,” he writes. “I have no problem with that and neither do my friends. And that’s precisely the point that fundamentally separates those of us who would defend a concept of radical diversity from those proponents of German guiding culture: we want to create a space in which one can be different without fear, while the other side wants to implement cultural criteria for belonging that by necessity exclude those who don’t align with their concept.”

The original German version of Czollek’s book was published in 2018, shortly after the far-right AfD had become the third-largest party in the Bundestag. Rather than spurring a backlash against extremism, other politicians took a page from the playbook, he argues, with the parties of the right, centre and left warning of the perils of nonintegrated newcomers.

Czollek views the AfD’s rise as a symptom as much as a cause – “Suddenly things everywhere are staining Nazi brown,” he writes – and he sees a different avenue for political success in the face of the far-right surge.

“I don’t believe Germany will win the fight against the New Right without the votes of (im)migrant, postmigrant, Jewish and Muslim citizens,” he writes. “And this critical – if perhaps unfamiliar – new alliance requires strong narratives, the willingness to accept self-criticism from all sides, and a political vision for a society beyond the current integration paradigm.”

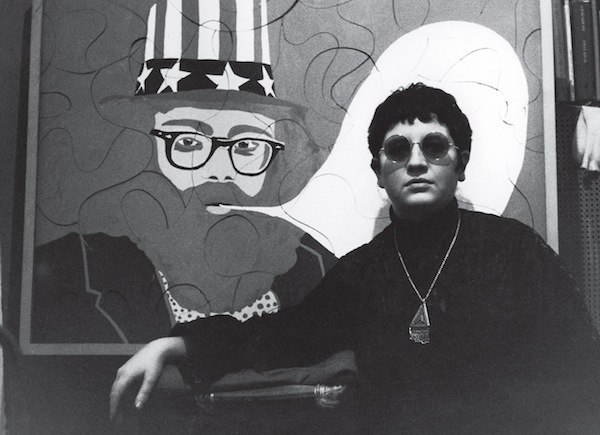

Czollek has a doctorate from the Centre for Antisemitism Research at the Technical University of Berlin, has published books of poetry, and is a co-editor of Jalta, a journal of contemporary Jewish culture. He has been involved in political and multicultural theatre in Berlin for many years but with this, his first nonfiction book (translated into English by Jon Cho-Polizzi), he burst on the scene as a contentious public intellectual. The opposition to his work evoked not just political challenges but also public efforts to discredit him based on his identity as a patrilineal Jew.

Czollek’s presentation, in conversation with Markus Hallensleben, associate professor in the department of Central, Eastern and Northern European studies at the University of British Columbia, was opened by book festival director Dana Camil Hewitt. The main festival runs Feb. 11-16.