At the close of what Western countries call Valentine’s Day, a tenuous ceasefire went into effect in war-torn eastern Ukraine. Unfortunately, the days prior to the truce were not what you would call all “hearts and flowers.” Up to the last minute, both sides pushed to make territorial gains. We can be sure that no love has been lost.

Needless to say, tanks, rockets and guns do not tell the whole story of the armed conflict. Beyond the military operations are the civilians whose lives have been affected.

One critical result of the fighting is that the overall health situation in Ukraine has rapidly deteriorated. (Even in peacetime, however, the health situation was not on par with Western medicine.) Recently, the United Nations reported that drug supplies are running out and that the country has seen a rise in the number of tuberculosis diagnoses. As there are not enough shelters for displaced people whatever their health status, some of these individuals are being sent to hospitals. This in turn has created a lack of treatment space for acute medical cases. To date, these are the statistics on the war in Ukraine:

- 5,486 people killed and 12,972 wounded in eastern Ukraine

- 5.2 million estimated to be living in the areas of conflict

- 978,482 internally displaced people, including 119,832 children

- 600,000 have fled to neighboring countries, two-thirds of whom have gone to Russia

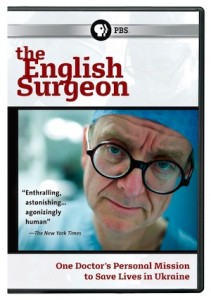

How can we in the West appreciate what is happening to the people living in the conflict zone? One unlikely way is to reconsider Geoffrey Smith’s powerful 2007 documentary The English Surgeon. The film deals with how medicine is practised in Ukraine and puts a personal face on what life (in more promising times, perhaps) is like for Ukrainians.

This film reveals how two dedicated neurosurgeons make do with scarce medical supplies with a goal to improve their patients’ quality of life. In the course of this sophisticated British-produced documentary, viewers become intimately acquainted with the hospital exploits of this medical odd couple: Dr. Henry Marsh, a British neurosurgeon, and his Ukrainian counterpart, Dr. Igor Petrovich Kurilets. Smith’s movie is enlightening and viewers can glean much about Marsh’s point of view. In his experience, performing the surgery itself is not the hard part, it’s knowing when to treat that’s complicated.

Early in the film, Marsh talks about the importance for him of helping other people; he questions what we are if we don’t try to help others. When the movie was filmed, Marsh had already been volunteering in Ukraine for 16 years. He tells us that when he first started his project, he found surgical conditions comparable to those that existed in the West 60 years prior. He was appalled at the misdiagnoses he encountered, and by the stories of patients that could have been helped had they received appropriate medical interventions earlier.

The film exudes irony and humor as viewers get to know Marsh. He explains that he always liked working with machines and using his hands. He also enjoys the sensory aspects of working with wood. At one point, he says that surgeons like blood, and he likens surgery to a kind of sport.

Kurilets displays no less of a quirky wit. For instance, he points out a painting hanging on his wall. In the picture are happy Cossacks sitting around a table. Kurilets thinks there are many similarities between Cossacks and surgeons. He comments that in the painting, the Cossacks could be gathered around an operating room table. He appreciates the Cossacks’ aggressiveness. Actually, his own pro-activeness has gotten him into trouble with the authorities; he later reveals that he was unemployed for two years following repeated run-ins with the Soviet system. Ironically, he currently rents rooms from a hospital run by the KGB, his former nemesis.

Kurilets is still a doer today, albeit perhaps slightly more pragmatic than he once was. He has plans to build a new hospital. He underscores his philosophy of life by explaining that the point is not to just make plans – something that happened a lot in the former Soviet Union – but to actually do, to get things done.

In fact, these two individuals are pragmatism personified. Marsh and Kurilets buy brain surgery tools in the local open-air market. Kurilets’ Bosch drill comes from this market. Marsh also regularly donates equipment to Kurilet’s practice. In an understated way, we learn some of the real costs of surgery in this area of the former Soviet Union versus the West: the 80 Sterling drill bits that Marsh’s hospital uses once will be used by Kurilets for 10 years.

Marsh also confronts deeper issues. He struggles with being able to leave patients with hope, even when there is nothing that surgically can be done.

One patient who can be treated is Marian, a young, rural man of limited financial resources. Marian has a brain tumor that could either leave him severely disabled or kill him. The doctors tell him that the only way they can help is by conducting brain surgery, but without anesthesia. Marian agrees.

The operating room in which this incredible procedure takes place is so small that, at one point, a member of the surgical team has to bend down, almost crawling to get to the other side of the room. Even in this incredibly tense scene, Marsh reveals his wry humor by saying that the healthy section of the brain should look “like a good cream cheese,” not rubber. He does not underestimate the tremendous vitality of the organ on which he operates, however. In surgery, he says, “We are the brain.”

Sharing some of the soul-searching he does in his practice, Marsh humbly admits that he has made some big mistakes. He narrates the painful story of one young Ukrainian patient that he brought to England for surgery. Marsh reveals that both of Tanya’s surgeries went terribly wrong. Even today, he can’t put Tanya’s story aside. He tells Kurilets that he thinks about Tanya a lot. Kurilets agrees that there were lessons to be learned from her case. But Marsh doesn’t just contemplate Tanya; he seeks physical contact with this lost patient. In a haunting moment of tremendous honesty and humanity, he pays a visit to her family members. He reveals to Tanya’s family how nervous he was before the visit.

The English Surgeon is a powerful movie, stunning, but frequently heart-wrenching. It displays not just the truth of the situation in Ukraine, but the truth about people.

The film is available online without charge at documentarystorm.com/the-english-surgeon or on Netflix Canada. You can view an interview with the filmmaker at pbs.org.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.

***

A number of organizations are trying to help civilians in Ukraine. Working at opposite ends of the life spectrum are two Jewish charities: the Survivor Mitzvah Project (survivormitzvah.org), which helps elderly Holocaust survivors residing in Ukraine, and Tikva Children’s Home (tikvaodessa.org), whose mission is to care for “the homeless, abandoned and abused Jewish children of Ukraine and neighboring regions of the former Soviet Union.”

***

While many are probably familiar with Jonathan Safran Foer’s book Everything Is Illuminated (which was also made into a film in 2005), the Good Reads website has assembled a list of other books dealing with Ukraine (goodreads.com/places/76-ukraine). The list contains fiction and non-fiction books for children and adults.