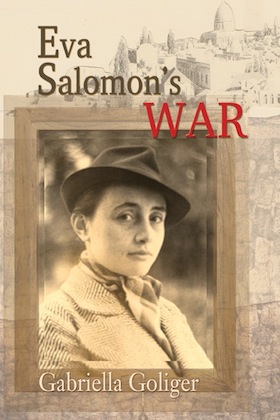

Gabriella Goliger’s Eva Salomon’s War is an intriguing novel. (photo by Ben Welland))

Award-winning Canadian author Gabriella Goliger has written Eva Salomon’s War (Bedazzled Ink Publishing, 2018), an intriguing novel set between the rise of the German Nazi state and the founding of the state of Israel – two complex historical phenomena whose aftershocks we are still experiencing. But, for Eva Salomon, those huge events are mainly engines moving her own story forward from timid German-Jewish adolescent to courageous Israeli young woman. The novel takes us through many intricacies of the competing historical strands that form the background of Eva’s life. Readers familiar with various bits and pieces of the history can connect the dots through her eyes.

Written as a first-person bildungsroman, the book opens as the Nazis close in on the Jews, who are wondering which of the many possible responses to embrace. Should they stay and resist? Stay, pray and keep their heads down? Should they emigrate, and, if so, where? Should they join the movement to build a Zionist workers’ state in Palestine? So many choices, so many unknowns, and so much peril attached to each decision.

Eva’s beloved older sister, Liesel, immigrates to a socialist kibbutz in the Galilee. Sixteen-year-old Eva and her embittered, widowed father migrate to Tel Aviv. We know what happens to the relatives who feel too old to make the trip.

The character of Eva is loosely based on Goliger’s own aunt. Letters between Eva and Liesel give us many illustrative details of Jewish life in Palestine in those years. In Breslau, they had enjoyed middle-class lives. In Palestine, they quickly have to learn working-class skills and they have to adapt to their shabby new realities among people with no time for pity or introspection.

The character of Eva is loosely based on Goliger’s own aunt. Letters between Eva and Liesel give us many illustrative details of Jewish life in Palestine in those years. In Breslau, they had enjoyed middle-class lives. In Palestine, they quickly have to learn working-class skills and they have to adapt to their shabby new realities among people with no time for pity or introspection.

Kibbutz life is physically harsh but relieved by the high level of ideological commitment between the comrades: “I sleep in a tent and the food is plain, but I never have to think about where my next meal is coming from. Everything is communal and allotted to me, down to my shoes and socks.” Eva flees the misery of life in her father’s tiny flat and finds a place to live with Malka, a Hungarian Jewish seamstress who helps her accommodate to her reduced circumstances.

Malka transforms Eva from a ragged miserable waif to a well-dressed young woman who can make her way in the vibrant, uncertain Jewish Palestinian world. Eva learns the meaning of “ein breirah” – no choice – a theme resonating not only throughout the novel but throughout the decades to the present day as one formative part of Israeli Jewish culture.

Eva finds work as an ozerit (cleaning lady) and starts putting together a life of sorts. She finds a music shop that affords her a bit of pleasure – “my refuge, my paradise” – phonograph records feeding her delight in classical music and her longing for romance. Fittingly, it is where she meets Constable Duncan Rees of His Majesty’s Palestine Police. Their romance encapsulates many conflicting layers of identity, culture, desire and belonging.

Throughout the novel, most of the characters are rent by doubts and competing loyalties. Only the fanatics of all stripes know certainty. The portrayal of Eva’s unbending Orthodox father, seemingly bereft of feeling for his wayward daughter, I found puzzling. We never see anything through his eyes, never understand his inner realities.

Eva is at war with her father, with all rigid religious and political belief systems, with her situation of loving the wrong person, and with her own competing claims of duty. Her personal war intersects with the fighting in Europe, the fighting between Arabs and Jews, the infighting between the various Zionist factions and, crucially, with the growing resistance to the British presence in Palestine.

Eva is a Jewish refugee. Duncan is charged with upholding British laws controlling Jewish immigrants. Despite the growing cultural-personal-political tensions, Eva enjoys their romance. She experiences pleasure and the delights of physical intimacy, which she keeps secret as much as possible. “The more he was my secret, the tighter, I felt, was our bond.” Their emotional intimacy is harder to sustain. One feels it can’t last and I wondered throughout how Goliger was going to handle it (no spoiler here).

The British White Paper on Palestine brings it all to a head. Tensions explode into violence all over the land, from many different directions, aimed at “traitors” to all the intersecting causes. For each faction, “we” are highly individuated and the others are an undifferentiated “they.” Eva, essentially an apolitical person, is helplessly caught up in the sectarian brutality.

One can’t help but read the novel through the prism of the tragic unfolding of events since 1948. Goliger vividly illustrates the human urgencies propelling Arabs and Jews in all directions, and the emotional realities behind all the ideologies.

Near the end, I was reminded of Anne Frank’s “In spite of everything, I still believe people are good at heart.” Eva reflects, “I believe a better world is dawning because … because ein breirah. I must.”

Deborah Yaffe lives in Victoria, where she formerly taught in the women’s studies department of the University of Victoria. An active secular Jewish feminist since reading Elana Dykewomon and Irena Klepfisz in the 1980s, she is grateful for the many Israeli individuals and organizations working against Jewish persecution of Arab Israelis and Palestinians.