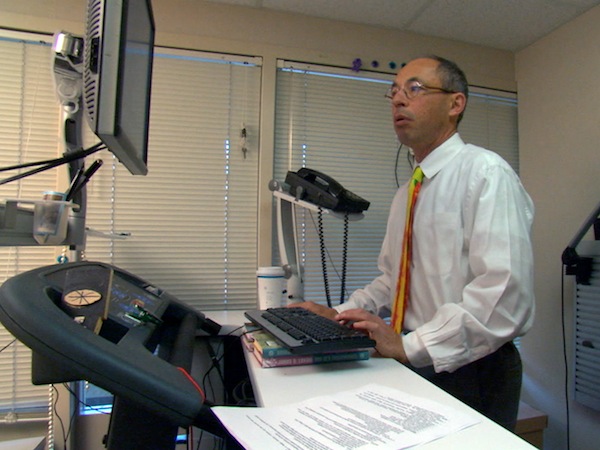

Dr. James A. Levine studies the health benefits of adding more movement to our lives. (photo from James Levine)

We are sitting too much – both at work and in our off hours. And all this sitting is doing us damage. But it’s not only about our health. It’s about how much we could be getting done, both professionally and personally.

When people read health-related articles or listen to health news, they “mentally categorize this information as health information. I think that is a mistake,” said Dr. James A. Levine, president of Fondation Ipsen, which, under the auspices of the philanthropy network Fondation de France, tries to promote scientific knowledge. “This isn’t about health. In the workplace, it’s about productivity: data suggests productivity – widgets produced per hour – improves by about 10 to 15%. In school, academic performance improves by about 10%, compared to kids who don’t engage in these activities and trials. Thinking about this as a health issue underserves the reader. Really, it’s about having a vital, exuberant, productive, happy life.”

While Levine – author of the 2014 book Get Up! Why Your Chair is Killing You and What You Can Do About It (St. Martin’s Press) – is a proponent of movement, he said sitting occasionally is not a bad thing. What is contributing to ill health, he said, is our culture of rolling out of bed, getting into our cars, sitting at an office desk and then driving back home to sit some more. Many of us shop online, order in meals, watch TV, play video games, check texts, email, use social media and go to sleep. Many of us are spending well over half the day, every day, seated.

“I think approximately 28 different chronic diseases and conditions are associated with excess sitting,” Levine told the Independent. “They range from excess body weight and obesity to metabolic conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease, to certain types of cancer, such as breast cancer … to mental health issues, such as low mood and depression, to mechanical problems in the body, such as back and joint pain, and all the way through to quite interesting and quite subtle conditions, such as impaired productivity, lower innovativeness, and so forth.”

There is no simple solution. “It’s easy to conjecture that a few simple tricks can solve problems like this,” said Levine. “But, if you think about it logically, if it’s taken society 50 years to get us down onto our bottoms, there can’t just be a few simple tricks to get us up. The modern workplace is actually designed to keep people seated, because it was felt, incorrectly at the time, in the ’50s and ’60s, that, if you kept a person at their desk, they’d be more productive. But, in fact, that’s been proven to not be the case.”

For some, like Levine, getting movement back into our lives means getting a walking desk. For others, it may involve having meetings with colleagues while we walk.

For some, like Levine, getting movement back into our lives means getting a walking desk. For others, it may involve having meetings with colleagues while we walk.

“Our brain neuros are continuously changing through neuroplasticity,” said Levine. “So, in other words, you can take a person with the brain structure of sedentary and convert them, through intervention, into a person who moves more. The reason this occurs is through neuroplastic factors that change the brain’s structure and biochemistry in response to, in this case, intervention.”

The younger a person is, the more neuroplastic their brain is and, hence, more adaptable, he said. The opportunity for an intervention to have the greatest impact is in childhood. As we age, it is harder for us to change.

“We did studies in primary schoolchildren which were fascinating,” said Levine. “We gave them five-minute motion stimuli or games during their lesson and we found that there was a disproportionate response in the children. In other words, if you give children a little nudge, they’ll move a great deal. You just have to give them permission to move. We found that, in slightly older children, ages 11-14, if you give them the same lesson, the children will double their daily activity. If, at the highest level, you alter the structure of the classroom, whereby movement is permitted … children will double their daily physical activity merely by changing their environment.”

For children, he said, the freedom to move will result in a 50% increase in activity; for adults, it will result in a 25 to 30% increase.

A first step to getting on a healthier track includes reading up on the topic, alerting your mind to the need to activate your body. When it comes to action steps, Levine advised people to start small and build on that.

“Look for two activities a day that you did seated, but that you can also do walking – things like weekly meetings with your manager, walk and talk,” he said. “Every lunch time, I won’t sit for half an hour. I’ll eat and sit for a quarter of an hour and walk for the other 15 minutes. I do it every single day. Every week, I’ve watched my kid go play hockey in the arena. Yeah, I’ll be there in the beginning, but I’m going to do a half an hour walk. We’re not talking about adding exercise. We’re talking about transferring sedentary time into moving time.

“My meetings are walk and talk. When I go out with my kids, we always walk and talk. When I go for an evening out with my wife, we walk to the opera or movie, or before dinner. If your evening out is too far to walk from home to, find a place to park your car that is walking distance to the venue. Park there and walk. While standing desks are good, moving while standing is even better. If not possible, consider placing your phone away from you, so you’ll need to get up to answer it and walk around your desk while you talk.

“Then, commit to your plan,” he said. “Yes, you’ve found five opportunities during the week to get up and move. You’ve built environmental cues to remind you to do it – on the fridge, the desk – and check it off on a weekly basis when you’ve met your goal.

“The last and final step might surprise you, because it may seem counter-intuitive, but it’s equally important to the other steps – get a good night’s sleep.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.