Community and faith can both comfort and oppress. A well-defined environment with clear expectations and rules can allow one to flourish, knowing one’s proper place and purpose in the world, or it can stifle one’s individuality, creativity and spirit, knowing that what is and what is to come is more determined by others than oneself. Self-realization and other universal themes, such as family, love and loss, are explored with a sensitive heart and a deft hand by Eve Harris in The Marrying of Chani Kaufman (Anansi Press Inc., 2014).

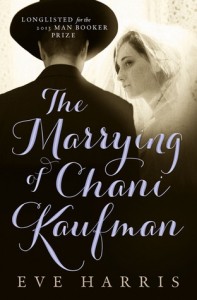

Since the Jewish Independent received its advance reading copy of Harris’ debut novel, which was first published in England by Sandstone Press Ltd. in 2013, The Marrying of Chani Kaufman was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. It has received many positive reviews, and this one will be no different in that respect. The novels characters are likeable and relatable; even the most intransigent of them has their understandable reasons for their views and actions. There are no malevolent people in this non-specific Charedi community living in Hendon and Golders Green, in the northwest part of London, England – although some do push moral boundaries in their efforts to get what they want, what they feel is right.

Since the Jewish Independent received its advance reading copy of Harris’ debut novel, which was first published in England by Sandstone Press Ltd. in 2013, The Marrying of Chani Kaufman was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. It has received many positive reviews, and this one will be no different in that respect. The novels characters are likeable and relatable; even the most intransigent of them has their understandable reasons for their views and actions. There are no malevolent people in this non-specific Charedi community living in Hendon and Golders Green, in the northwest part of London, England – although some do push moral boundaries in their efforts to get what they want, what they feel is right.

To write a novel that is simultaneously critical of and sympathetic to a community takes skill. Harris writes about religious people, not a religion per se, and she writes about these people with respect and knowledge, humor and pathos. She succeeds in telling a story about people living in a world that will be foreign to most readers and explaining it without becoming stilted or lecturing.

The Marrying of Chani Kaufman centres on four people: the bride and the groom, Chani and Baruch; the rebbetzin; and the rebbetzin’s son, Avromi, who is good friends with Baruch. It starts at Chani and Baruch’s wedding in November 2008 and goes back in time – several months for Chani and Baruch, when he first sees her; to 1981 for the rebbetzin, when she met her husband and began her journey to orthodoxy; and to 2007 for Avromi, when he met and fell in love with Shola, a non-Jewish fellow student at university. When the novel begins, Chani and Baruch are about to start their “real life,” as Chani describes it, the rebbetzin is well into her crisis of faith and Avromi’s double life is becoming difficult to maintain.

By the time the matchmaker arranges for Chani, 19, and Baruch, 20, to meet, at his insistence to his mother – who does not approve of the match for a few reasons, most notably the Kaufmans’ lower economic status – both had been on several arranged dates with other potential mates, to no avail. They both don’t quite fit the mold of the perceived ideal Charedi wife or husband, and both are unwilling to settle.

At school, when she was 15, Chani’s “garrulousness had got her into trouble,” she “was considered audacious but gifted,” “everything interested her – the little she could get her hands on.” She “had learned to walk and not run…. She had longed for freedom of movement but had been taught to restrict her gait.” In agreeing to be married to Baruch, “She hoped that the bell jar might finally be lifted. Or at least she would have someone to share it with.”

That latter hope, at least, does seem possible, as Baruch, too, thought his “life felt narrow: the pressure to succeed, to be a rabbi, to please his father. His quick analytical mind was to be harnessed to the Talmud. The English degree he longed to study remained a blasphemous secret buried in his heart.” As did Chani, he acted out in small ways, listening to rock music or reading novels that were not permitted. So, perhaps together they will be able to negotiate a Jewish life that feeds more of their being and soul. Perhaps there will be a happily ever after for them. Their parents seem reasonably content, albeit with their respective – and not insignificant – problems.

The future well-being of the rebbetzin and her family is also left to readers’ imaginations, the rebbetzin’s questioning seeming to have more far-reaching implications than her son’s transgression. Sparked by a miscarriage – a devastatingly described incident in which the emotional distance between her and her husband becomes apparent – the rebbetzin begins to deal with long-latent grief from a much-earlier tragedy. This process, at least initially, separates her from her family, her community, her faith. Where it takes her is not revealed.

As much as The Marrying of Chani Kaufman offers readers a glimpse into the lives of others, it offers the possibility of finding out more about ourselves and our own place in the world.