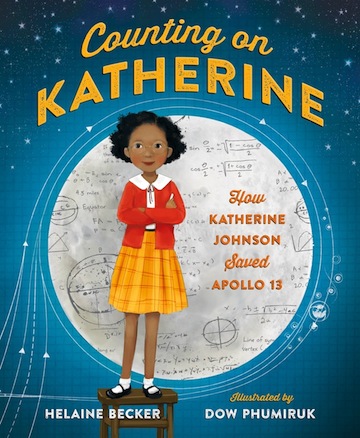

Delightful. That’s the first word that comes to my mind for two new hardcover children’s books by members of the Jewish community that will soon find their way to my youngest nieces’ bookshelves: Pip & Pup by Eugene Yelchin (Godwin Books) and Counting on Katherine: How Katherine Johnson Saved Apollo 13 by writer Helaine Becker and illustrator Dow Phumiruk (Christy Ottaviano Books).

Yelchin’s wordless book begins with a chick hatching. On a farm somewhere, having just come out of her shell, Pip sees the world for the first time. She spies a puppy sleeping under cover of a tractor. Fearless, she goes right up to Pup’s nose to say hello. When Pup awakens and barks in greeting, Pip is thrown into a panic, not quite prepared for the full size of her relatively large new friend.

When the rain starts, Pip literally climbs back into her shell, but just to stay dry. She is no longer afraid. In fact, when she sees Pup’s distress at getting wet and at the sound of the thunder and the force of the rain, she offers what help she can. The two start to play even before the sun comes out again. A broken eggshell dampens spirits momentarily, but then it’s Pup’s time to fix things, which she does.

Pip & Pup is a simple story that is evocatively illustrated using warm colours, texture and layers, combining pastels, coloured pencils and digital painting. There is a depth to the art and the story. Children and their adult readers will have fun asking each other questions as they go along. Do you think Pip is brave to say hello to Pup? Do you like the rain? How is Pup feeling right now? How would you feel if something of yours broke?

Many questions will arise from reading Counting on Katherine, as well, though some of them will require a different kind of reflection, as the story touches upon racism, sexism and other such topics – in an age-appropriate way for readers 5 and up.

Many questions will arise from reading Counting on Katherine, as well, though some of them will require a different kind of reflection, as the story touches upon racism, sexism and other such topics – in an age-appropriate way for readers 5 and up.

Becker interviewed Katherine Johnson, who turned 100 years old on Aug. 26, and Johnson’s family for this picture-book biography. Johnson was a mathematician at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and, among other things, her manual calculations were crucial in bringing the crew of Apollo 13 back to earth safely after it was damaged while in space.

In Counting on Katherine, we meet Johnson as a young girl: “Katherine loved to count. She counted the steps to the road. The steps up to church. The number of dishes and spoons she washed in the bright white sink. The only things she didn’t count were the stars in the sky. Only a fool, she thought, would try that!”

And Johnson was anything but a fool. She skipped three grades in elementary and was ready for high school at 10 years old. “But back then,” writes Becker, “America was legally segregated by race.” Johnson’s high school didn’t admit black students, so her father, by “working night and day, he earned enough money to move the family to a town with a black high school.”

Johnson’s next challenge was that, as a woman in that era, she was relegated to the teaching and nursing professions, so she became an elementary school teacher. However, in the late 1950s, the space race began, and NASA’s predecessor began hiring thousands of workers. “It even started hiring black women – as mathematicians.”

Johnson excelled at NASA and her work was integral to the United States’ space program, not just to the Apollo 13 mission, and Counting on Katherine has an epilogue that gives some additional information about Johnson. As well, Phumiruk’s imaginative digital artwork is also information-filled, clearly showing Katherine’s longing to learn, as she gazes from her bedroom window at the night sky; her joy with numbers, as she fills chalkboards with them; her anger at not being allowed to attend her town’s high school; her meticulousness, as she calculates a safe journey for Apollo 13. Counting on Katherine is a wonderful book.