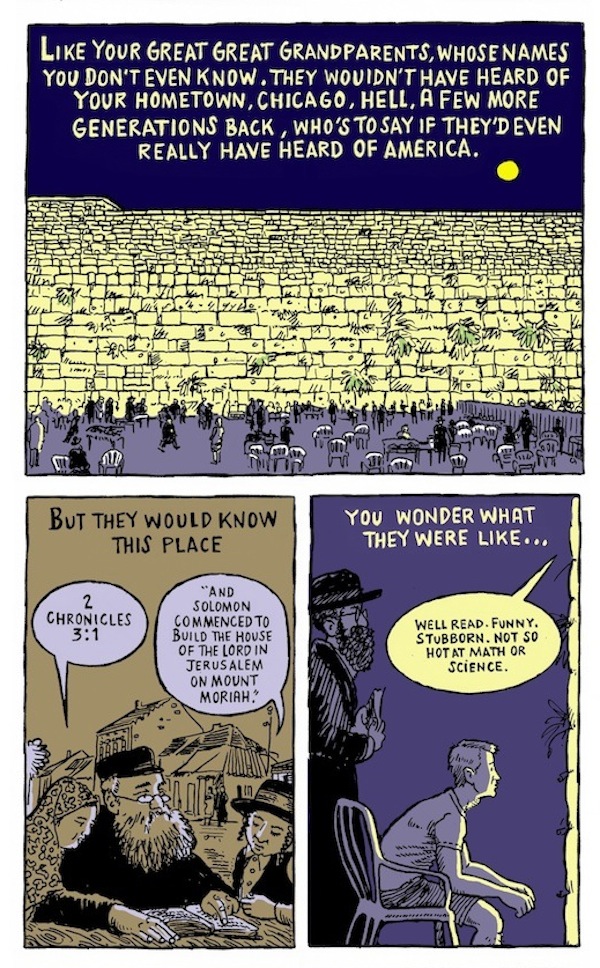

From The Completely Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green, by Eric Orner.

It was never on Eric Orner’s agenda to go to Israel. He resisted his mother’s entreaties to join a young people’s synagogue trip to the Jewish state. A relatively secular upbringing and a tendency to play hookey rather than attend Saturday morning religious classes meant he emerged into adulthood without a sense of strong connection to Israel or Zionism.

As a young adult, he was busy with a dual career that had him working days in the office of Barney Frank, the iconic, gay, Jewish congressman, and spending his nights drawing an iconic gay, Jewish comic strip that, at its height, was running in about 100 alternative and LGBTQ newspapers across North America.

It was circumstance, not Zionist fervor, that eventually took Orner to Israel, and among the results of his three years there is a series of comic strips that are, in turns, disturbing, thought-provoking and moving.

***

Starting in 1989, Orner drew the self-syndicated cartoon strip The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green. For 15 years, it was a cult favorite that followed a cast of sharp-tongued characters across a dramatic time in the evolution of the AIDS epidemic, the gay rights movement and politics in general, while capturing the spirit of the time in ways that perhaps only the medium of a comic strip can. The cartoon is cut through with Yiddishisms and sometimes unmistakably Jewish humor and sensibilities. Orner acknowledges that Ethan Green is, like him, a short, culturally Jewish, gay man, but the strip is not about Orner’s life.

“There’s 15 years of episodes of things happening to him and those things didn’t happen to me,” he said. “It was about somebody who had characteristics like me but it wasn’t about my life.”

For those who missed the strip in its serial incarnation, or who want to catch up, a compilation has recently been released, titled The Completely Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green.

When The Mostly Unfabulous Social Life of Ethan Green was turned into a film, in 2005, Orner figured that was a good time to wind up the strip and make a change. He had spent a decade working in the Boston and Washington offices of Frank, the recently retired longtime congressman whose name is synonymous with Wall Street reform, consumer protection and pithy lines. Frank had met Orner around Boston, where the Chicago-born Orner was studying at Tufts University.

“I forget who first raised the question that he would work for me,” Frank told the Independent. “He’s very smart, he’s very thorough. The fact that he was doing the cartoons made him more interesting. It wasn’t relevant to his work one way or the other.”

But while Frank is noted for humorous quips, Orner apparently saves his best for the page.

“What I found in Eric is that his wit and humor comes out more in his writing,” Frank said. “He was not shy, but not nearly as outgoing as the cartoons.”

Frank said Orner has one of the hardest work ethics he’s encountered, which may help explain how he held down an intensive job as an aide to one of the country’s leading politicians while also pumping out a bi-weekly comic strip and distributing it, in the days before the internet, by stuffing it into envelopes. To top it off, during this time, Orner also studied law and was called to the bar.

Frank, who introduced the first gay rights bill in Massachusetts, in 1972, is a central figure in the movement for sexual orientation equality, which experienced its most dramatic achievement when the U.S. Supreme Court ordered marriage equality for gay and lesbian couples, just days before Frank spoke with the Independent.

“No social movement in America, that I can think of, has moved remotely as quickly as this one,” Frank said. While the congressman was fighting legislatively, he credits Orner for playing no small part in the movement as well.

“This was not always an easy fight for people and there is also this tendency for people in movements to be grim and to talk about all the negative stuff,” he said. “But having someone who saw the humor in it was affirming in a way.”

***

Orner left the congressman’s staff to follow his dream to draw full-time. He moved to California and got a job as an animator with Disney.

“Most cartoonists I know aren’t lucky enough to do it full-time,” Orner said. “The only time I’ve had that experience was the time when I was working in animation and really they both involve drawing but they’re very different.”

It was not everything he had imagined. Orner acknowledges he is a good animator, but maybe not as good as some at Disney, who accused his Tinkerbell of flitting across the screen like a Black Hawk helicopter. Even this was not the main problem.

“That was not about my creativity, that was about Uncle Walt,” he said. “Animation is, in some sense, factory work.”

Like a lot of factory work, much of it was moving overseas. His boss got a job as head of a project in Jerusalem, which was at the time competing with Tel Aviv to become a media industry hub.

“So they built a beautiful animation facility and a bunch of Californians, including myself, went over there to work on a film.” The project never saw light, which is common enough in animation, he said. But, again, he was moonlighting with his own projects.

“Suddenly there I was in Israel,” he said. “It changed my life in many, many ways. I didn’t want to go and I wasn’t very happy about it, but that all changed and I fell in love with it and now I worry about it every day of my life. I disagree with a lot of things that are happening over there and yet I have dear, dear friends.”

The strips he wrote in Israel are part of a to-be-published volume called Avi & Jihad. One strip, called “Kotel 3 a.m.,” is a powerful short story of a midnight stroll to the Western Wall, where a skeptical American Jew finds resonance and a connection to the millennia of history there. When he tells his colleagues at the office about his stroll, it evokes stories of “nutcase Americans” who arrive from Great Neck or Savannah or Palo Alto and start speaking in tongues. Another is about the unadvisable idea of not taking seriously the El Al security agents. In one deeply dark strip, a love story between a Jewish man and a Palestinian Arab man turns into violent carnage that Orner said is not specifically about a single incident, but clearly evokes the murderous attack on a gay youth centre in 2009, and which has added resonance after the stabbings at this summer’s Pride parade in Jerusalem.

Orner’s politics were on his sleeve – or, rather, on the page – when he was writing Ethan. Some of his Israeli comics are less overt and more slice-of-life, but he pulls no punches when speaking about Israeli policies and the positions of American Zionists.

“I think that if it’s fair game to be critical of the Likud in Tel Aviv, then it should be fair game to be critical of it in Washington, D.C.,” Orner said. “I think we’re a little afraid to be critical. This is not the Israel of Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan and David Ben-Gurion.”

Orner said that if you can love America and not love George W. Bush, you can love Israel and be critical of its leadership.

“Sometimes, dialogue is unpleasant and uncomfortable and harsh,” he said. “I think we’re tough enough to handle that. I think we’re strong enough to have this conversation without going to pieces, thinking, oh God, our campuses are full of antisemites.”

Orner was in Israel from 2007 to 2009, which was the aftermath of the Second Intifada, the tensions of which are depicted in his pieces from those years.

“They are constantly under threat,” he said of Israelis. “Do I understand why people would then go to the polls and vote for Netanyahu? I do. Because you might disagree with him but, in the end, you think he’s a tough guy and that’s what we need.”

But Orner thinks there is an element in Israeli politics that doesn’t want a resolution to the conflict.

“I’m a Zionist, but I think the settlements, settlement activity, has been counterproductive from the beginning and I think there’s a lot of people that promote the settlement activity particularly because it is counter-productive to peace.”

Orner recognizes that his opinions may not be a consensus viewpoint, even in his own circles.

“I make a lot of people mad,” Orner said. “I’m not sure my old boss agrees. I know my stepfather disagrees. I know my best friend disagrees. But, having lived there for three years, that’s what I saw. I saw settlements over the [Green] Line and, if I were a Palestinian, that would enrage me also. I don’t know what the answer is, but my guess is building more settlements over the line quicker isn’t the answer.”

After the global recession hit and he lost his job in Jerusalem, Orner returned to Frank’s office and remained there until the congressman retired in 2013. Orner is now a speechwriter in New York. He is looking for a publisher for his Israeli cartoons and is working on another book depicting his time in California.

He has no regrets about his three years in Israel. It piqued his interest in Jewish history and changed him.

“I became far much more appreciative of my connections to Jews from other parts of the world, not just Israel, but France, Italy, Morocco, Iraq,” he said. “I looked out my window – I had this apartment that I could see the gold dome of the Al-Aqsa Mosque from my window – I lived in a hilltop neighborhood called Abu Tor and I looked right down on the Old City walls. You can’t live there without being more interested.”