“Twins run in the family, you know,” Stella ter Hart’s mother, Sophia, said to her nonchalantly when Stella was pregnant with her first child. That this was news to Stella is a first sign that there was a great deal about her family she did not know. In fact, she wasn’t aware she had much family at all.

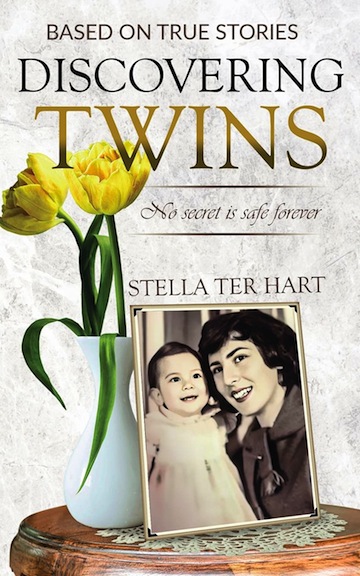

Thus begins Stella ter Hart’s book Discovering Twins: A Journey into Lives.

Thus begins Stella ter Hart’s book Discovering Twins: A Journey into Lives.

As a high school graduation gift, Stella and her mother made the trip from Estevan, Sask., to Holland. There, she meets an endless web of confusingly related kin – almost all on her father’s side. A visit to the home of family on her mother’s side raises questions in the teenager’s mind.

“‘Oom Jacob and Tante Becca are Jewish,’ I stated rather than questioned, ‘no one other than Jewish people are named Jacob and Rebecca.’

“And, in a style completely out of character for her, almost resignedly, my mother replied, ‘Yes, they are.’

“There was no further clarification of her answer, no offering up of a tidbit of a childhood memory, as might be expected when revealing so vast a thing as religiously specific relatives for the first time.

“‘So, if Oom Jacob is your first cousin, and he has the same last name as your mother’s maiden name, then he is the son of your mother’s brother,’ my new skill of dissecting family relationships now sharply honed, I added, ‘so your mother must have been Jewish, too.’

“In a split second, she came back at me, her voice strident with an unexpected, insistent, and lashing response, ‘NO! My mother was NOT Jewish. According to the Germans, she was Italian because she married an Italian.’”

Whether that logic ever truly convinced her mother, Sophia, it did not sit well with ter Hart. After her mother’s death, ter Hart began a genealogical quest. Slowly and excruciatingly, she pieces together the tragic fates of almost the entire maternal line.

“Our extended circle of family, formerly numbering over 1,200, was reduced to the less than 20 who returned, or were known to have survived, creating a psychological tsunami shock-wave impacting existing and future generations,” writes ter Hart.

The book recreates ter Hart’s prewar extended family, flashing back from postwar comfort in Canada. She captures what must have been a dawning realization among Dutch Jews in the earliest months of what became the Holocaust, as relatives who were relocated to the east inexplicably never wrote back.

“How many ‘workers’ did this totalitarian German regime require for its slave labour force? Where was the food to feed them all going to come from and the rooms to house them all? Supplies were already hitting dangerous lows in the cities, and rationing was strictly enforced.

“The unsettling sentiment echoing throughout the community for months raised its voice again. What in heaven’s name would the Germans do with grandparents and babies? This didn’t seem like a necessary part of war. This was something else.”

As ter Hart’s research expands, numbers and dates leap off the page.

“The ages and dates are, each time, an emotional shock. The eye at first does not even see, let alone accept, the horrific truths the numbers expose. Mothers with all their young children around them all killed at the same time, or an elderly couple, obviously arrested and deported together, also murdered together. The gruesomeness and cruelty of it all is staggering and overwhelming,” she writes.

On Sept. 30, 1942, 103 family members were murdered at Auschwitz, the youngest 15 years old, the oldest 54. On June 11, 1943, 64 family members were gassed at Sobibor, aged 2 to 68.

The author seeks to build suspense, but her discoveries are, generally, no surprise to those with knowledge of the history. The emphasis on twins – across generations, the family seems to have an occurrence of twins about twice the average – gives the reader an anxious sense that, at some point, some family members are going to fall into the hands of the monstrous Dr. Josef Mengele.

“Not wanting to know, but needing to know, I researched the lists of Mengele Twins, now publicly available. None of our family were on that list, as most had been deported and killed before Mengele began his murderous experimentations. Small comfort,” she writes.

The narrative at the beginning of the book devolves near the end into something of a genealogist’s notebook, with records, short biographies and charts. Generally, the book hangs together, though an editor’s hand could have been firmer, to avoid easily avoidable clangers like misspelling Anne Frank’s name.