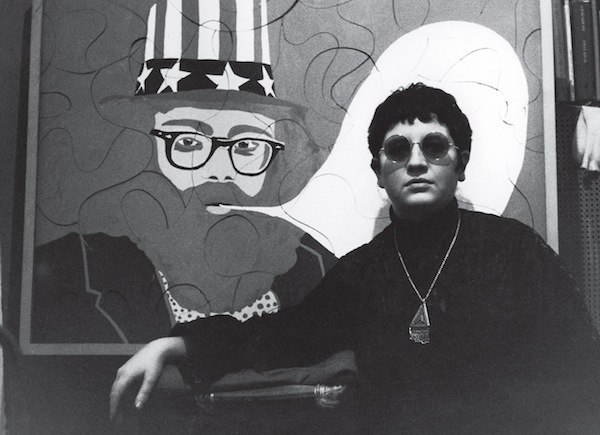

Shai Avivi, left, and Noam Imber are excellent as father and son in Here We Are. (still courtesy VIFF)

Understated and poignant are just two of the words I’d use to describe the screeners I watched in anticipation of the Vancouver International Film Festival, which opened Sept. 24 and runs to Oct. 7.

As with most everything these days, much of VIFF has moved online; however, there are still in-person screenings and talks, with audience sizes limited. And, as with other film festivals, online viewing is geo-blocked to British Columbia, meaning that you can only watch the movies if you are physically inside the province. The new format should allow for more access to the festival offerings and, while there will be those who miss dressing up and going out to the movies, there will be many people excited to be able to attend VIFF in their pajamas at home, me being one of them.

Last week, I watched two full-length features and two shorts: the narrative Here We Are, directed by Nir Bergman (Israel/Italy); the documentary Paris Calligrammes, directed by (and about) Ulrike Ottinger (Germany/France); The Book of Ruth, directed by Becca Roth (United States); and White Eye, directed by Tomer Shushan (Israel).

Every year, the Jewish Independent sponsors a selection at VIFF and, this time round, we’ve chosen a wonderfully written, acted and filmed movie. We generally have zero time and little information on which to base our choice, so I feel particularly grateful to have lucked out with this gem.

Here We Are is the story of a father who both will do almost anything for his autistic son, but who also uses his son as an excuse to not deal with the larger world. Aharon (played with incredible delicacy by Shai Avivi) has left his job to care for his son Uri (acted by Noam Imber, who gives an empathetic and strong performance). Aharon and his wife Tamara (played by Smadar Wolfman, who does a wonderful job, too) are no longer together, and Uri’s care has been left in his father’s capable and loving hands.

But Uri is an adult now and, to grow, we need space and the ability to direct our own lives. Tamara recognizes this and has worked hard to find Uri a good home, where he will be able to make friends and participate in activities with his peers. Aharon, however, is unable to let go and, though he also wants the best for Uri, he undermines Tamara’s actions – not only in words, but he takes Uri on the run.

The script by Dana Idisis leaves room for the pauses and emotions that make Here We Are an excellent film. Avivi’s face speaks more than a thousand words and you can see the inner conflict as his character struggles to accept that his son no longer needs him as much. The chemistry between Avivi and Imber makes the father-son relationship believable and compelling. And there are no “bad guys” here, even though mother and father differ in their opinions on parenting.

“I love the characters, the relationships, the way Aharon has reduced his needs to accommodate his son’s, and the transformation they experience throughout their journey,” reads the director’s statement. “I believe that, if I’m able to convey these characters as they are, from the written page to the screen, together with the bittersweet and humorous tone of the script, the audience will also fall in love with them.” Bergman accomplished his goal, and then some.

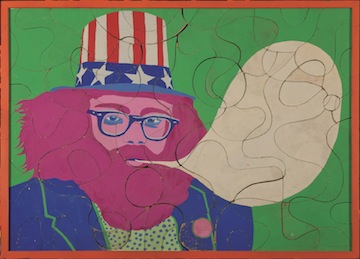

Paris Calligrammes is also very watchable and engaging. I’ll admit to never having heard of Ottinger before, so I was looking forward to learning more about her, her artwork, her photography and what eventually inspired her to filmmaking. However, while I thought the documentary was esthetically pleasing and gave a tangible sense of how exciting it would have been to live among the artistic elite in Paris during the 1960s, I couldn’t tell you much about Ottinger herself and what she contributed to the thoughts, images and culture of those turbulent times. But, I guess, perhaps it is assumed that one knows these things already.

Ottinger does offers some interesting and valuable commentary – read by British actress Jenny Agutter – but, for whatever reason, I didn’t think it was enough. The film is named after the bookstore Librairie Calligrammes, which specialized in antiquarian books and German literature, and was where Jewish and political émigrés hung out, along with others who we would now call cultural influencers. Ottinger drove to Paris in 1962 from Konstanz, Germany, to become, in her words, a great artist; to follow in the footsteps of her heroes and heroines. She not only follows those footsteps but walks alongside the likes of Tristan Tzara, Marcel Marceau, Raoul Hausman, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and countless others as well known.

Some of the most interesting parts of the film are about Algeria’s years-long war of independence from France (1954-1962) and the situation at the time with respect to the appalling treatment of Algerians living in Paris. Clips are shown of a peaceful demonstration held on Oct. 17, 1961, that was violently broken up by police. According to the film, 200 to 300 people were killed that night alone and, to this day, there has not been an investigation and no one has been held accountable for the deaths; even opposition newspapers didn’t report on it at the time and photos vanished from newsrooms. Ottinger notes that the order for the police to attack was given by then-chief Maurice Papon, who, under the Vichy government, had organized the rounding up of Jews to be murdered during the Holocaust.

This is a film that, I think, would be most appreciated on a big screen, but is still worth watching, for its content, yes, but mainly for its creative use of archival footage and interview clips, photographs and current-day images and filming. The documentary starts with a quote from Conseils au Bon Voyageur by Victor Segalen, advice that Ottinger has “gladly followed”: “Advice to the good traveler – A town at the end of the road and a road extending a town: do not choose one or the other, but one and the other, by turns.” If one needed inspiration to live by the conjunctions “and/both” rather than “either/or,” Paris Calligrammes might offer it.

While Paris Calligrammes is the product and vision of a longtime filmmaker, The Book of Ruth comes from the imagination of Chen Drachman, and is the first film Drachman has written and produced. She also co-stars in this exploration of how important it is to have symbols – in this instance, represented by an historical figure – around which to rally or by which to live one’s life.

The short takes place during the happiest, smallest (five people) and shortest seder that I’ve ever seen, and focuses on Ruth – played by veteran actress Tovah Feldshuh – and whether she is really the grandmother her granddaughter, played by Drachman, grew up knowing. While the scenario postulated is unbelievable, Feldshuh offers the gravitas and has the talent to make viewers look beyond that fact and consider the questions raised in the film about the stories we build around some people – their role in a war or a political movement or an artistic endeavour, whatever – and how that story or image can help make us, living in another time, feel less alone, more understood, etc.

Symbolism, of course, can be positive and negative. Racist views and bigotry also come from the stories we have learned and tell ourselves. And White Eye, both directed and written by Shushan, does a superb job of illustrating how prejudices and privilege we may not even know we have can lead to disastrous consequences.

The main character of Omer is played by Daniel Gad with convincing stubbornness and obliviousness at first, then quiet shock at what happens as a result of his desire simply to take back what is his. When he comes across his bicycle, which had been stolen, that’s all he wants to do: cut the lock off and take it back. Even after he meets the bike’s new owner, Yunes – actor Dawit Tekelaeb will win your heart with his touching portrayal of a hardworking father and husband who bought the bike so he could take his daughter to kindergarten – Omer wants his property back. Even when Yunes’s boss (Reut Akkerman) argues on her employee’s behalf, Omer refuses to budge even the smallest bit. Only after the police become involved and Yunes, an immigrant from Eritrea whose visa has expired, is taken away, does Omer realize the full implications of his actions. By then, of course, the damage has been done. And it’s much more devastating than having had one’s bicycle stolen.

For the full film festival lineup, schedule and tickets, visit viff.org.