Bob Bossin (photo by Suzanne Kimpan)

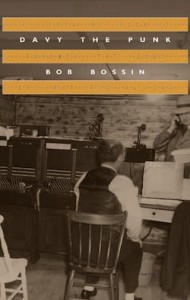

Bob Bossin, a well-known Canadian folk musician, recently released a book about his father, Davy the Punk: A Story of Bookies, Toronto the Good, the Mob and My Dad. The book is a compilation of true-life stories about the author’s father, David, a legendary figure in the underground gambling scene in Toronto in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, but it’s much more than that. It is also a social commentary on Canadian life off the lawful path in the first half of the 20th century.

Simultaneously with the release of the book, on which it is based, Bossin is touring with his new one-man musical, Songs and Stories of Davy the Punk: The Very Jewish Story of My Father’s Life in the Gambling Business. He brings it to Havana Theatre June 3-7, and recently talked to the JI about both projects.

JI: How and when did you come up with the idea for this book?

BB: My father died when I was young, just 17, but I heard many stories about him. One afternoon in the early 1970s, I stopped for lunch at the United Bakers Restaurant on Spadina Avenue. It had been in Toronto since 1912 and it had a counter man as old as Methuselah. I sat at the counter and started kibitzing with him. I asked him how long he had lived in Toronto.

“Longer than my teeth,” he said in Yiddish. So I asked him if he knew the Bossins.

“Sure,” he said, “I knew the Bossins. I knew Hye, Celia, Sady, Bessie, Davy….”

“Davy was my father,” I told him.

“Sure, I knew Davy. We used to call him Davy the Punk.”

“Davy the Punk? Why Davy the Punk?”

“Because he was a punk kid. He was a gangster.”

After that, I became very interested in my father and, as it turned out, the police had felt the same way. While my father was not a man who wrote things down, the police wrote a lot about him. So I started to haunt the archives and newspaper morgues. I tracked down old bookies, old cops and old judges and, over the years, I pieced together my father’s story.

JI: Did you use your imagination to fill the gaps or when memory was fuzzy?

BB: Of course, the imagination is very much involved, even as you are trying to stay as close to the facts as possible. People live lives, not stories. Turning a life into a story is an imaginative act.

JI: Could you tell us something about the research you did for the book?

BB: Calling this book a memoir was the publisher’s idea. Fair enough: books have to be categorized, and “storybook” wasn’t one of the options. But that is how I think of it. This is the story I might tell you on a summer night, if I really got wound up. I suppose it is a memoir of sorts, but my father died when I was a teen, so my personal memories of him end early. Of necessity, I have reconstructed much of Davy the Punk from what others told me, and from the documents my father had nothing to do with.

I did get some of the story straight from my father, Davy Bossin. Among friends and family, Davy was not secretive about his past, and I liked nothing better than listening in when he told his stories. I only wish that I had asked him more questions, and that I had a better memory than I do. Of course, in the end, our fathers’ lives always remain a mystery, and mine no less, despite my best efforts to snoop.

Over the years, I have learned a lot about what Davy did, but how he did it, I can only guess. For instance, I know that he went to New York around 1950 to tell Frank Costello he was quitting the gambling business. But how did he feel boarding the train? Worried? Confident? Nonchalant?

Or there is Bill Gold’s story of Davy happily kibitzing with the murderous Fischetti brothers in a Cleveland gambling club in 1948. Was Davy really as relaxed as his friend remembered a half-century later, when he was 92? I decided to take Gold’s word and reported the story that way. The book is peppered with choices like that … as I kept after Davy the Punk through all the obstacles and dead-ends inherent in chasing a man with a 50-year headstart.

My mother was another important source… After her and my father, I am, in a way, most indebted to Alex Haley, the author of Roots. Sometime in the late 1970s, Haley called everyone to go out with a tape recorder and tape their family elders’ stories. I thought that was a terrific idea…. I recorded interviews with a dozen aunts, uncles and cousins, filling many a cassette. I always asked them about Davy.

JI: You talked to people, searched in archives and libraries. What else?

BB: The internet. Suddenly every paper ever published by the Toronto Star or the Globe and Mail was online and searchable. When I searched 1940, up came Gordon Sinclair’s live coverage of the raid on the Canadian Turf and Sports Bulletin, my father’s business. Overall, the books, articles and theses I read number in the hundreds.

JI: How long did it take to write the book?

BB: It took five or six years. I do lots and lots of re-writing.

JI: How and when did the book get turned into a show?

BB: That was my idea from the get-go. Performing, telling stories on stage, both as songs and prose, that’s what I have done for a living all my life. The show premièred at the Ashkenaz Festival in Toronto two years ago, as a sort of one-act musical reading. It has come a long way since then. I developed it through a few other preview performances that fall, and then put it aside. I’ve just started performing the full version. So far, it’s been four shows.

JI: How much of the book went into the show?

BB: The show is maybe one-tenth of the length of the book. They each have their own tone. The book goes much deeper into the history of my father’s world, particularly of the gambling business, the mob, the behind-the-scenes workings of the authorities, the antisemitism of the times. But the show has the magic of a live theatrical experience and, of course, it has the music.

JI: You’re the author as well as the performer. Do you change the show depending on public reaction?

BB: So far, yes. There’s nothing like getting it in front of an audience to see how it connects. There is a scene in the show now that wasn’t there until very recently. It was a piece I did at a couple book launches. People reacted to it so strongly I thought maybe it should be in the show. Once I put it in, it suggested other changes. It’s made for a significantly better show, I think. Eventually, I discover the best way to tell the story, and then it stays pretty much as scripted.

For a review of Bob Bossin’s Davy the Punk: A Story of Bookies, Toronto the Good, the Mob and My Dad, see page “A family underworld” by Robert Matas in this week’s issue. For more on the one-man show, visit the website davythepunk.com.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at olgagodim@gmail.com.