They both made headlines in their day, and then were more or less forgotten. A social climber who ends up convicted of killing his wife in one instance, an inventor-turned-money launderer in the other. Two very different men living in different eras who achieved the wealth and lifestyle they sought, then lost it all in spectacular fashion.

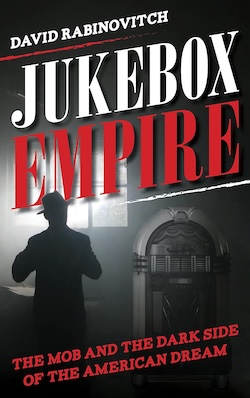

Historian Allan Levine and filmmaker David Rabinovitch close the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival on Feb. 15, 8 p.m., at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver with the event Jewish True Crime Stories, moderated by SM Freedman, who spent years as a private investigator in Vancouver before becoming a bestselling author of psychological thrillers. Levine will talk about his latest book, Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder (2020), and Rabinovitch will talk about : The Mob and the Dark Side of the American Dream (2023), his first book.

Both true crime publications have a similar structure. They both have a cast of characters at the beginning, followed by a prologue or preface, then the narrative proceeds chronologically, beginning with each protagonist’s origin story, and following the circumstances and decisions that led to their headline-grabbing lives. Both books have extensive notes and bibliographies. Levine and Rabinovitch each read more than a thousand pages of court transcripts and related documents, like witness testimonies and letters, as well as newspapers of the day. These types of resources, written as events were unfolding, allow both authors to tell their stories with an immediacy that propels readers along. In both books, it feels as if what we’re right in the midst of what is happening.

For Levine, the idea of exploring Toronto-born opportunist Wayne Lonergan’s conviction for the Oct. 23, 1943, murder of his wife, Patricia Burton Lonergan, the daughter of a wealthy German-Jewish family in New York City, came from reading a 1948 Cosmopolitan article by Raymond Chandler. The renowned detective fiction writer listed Lonergan’s case as #9 in his list of the “10 greatest crimes of the century.” There have been a couple of novels based on the case and, writes Levine, “Over the years, the story of the murder, with the requisite number of theories about Lonergan’s sexual identity, has been told and retold in countless tabloid newspapers and magazines and remains a favourite topic of crime and mystery bloggers.”

For Levine, the idea of exploring Toronto-born opportunist Wayne Lonergan’s conviction for the Oct. 23, 1943, murder of his wife, Patricia Burton Lonergan, the daughter of a wealthy German-Jewish family in New York City, came from reading a 1948 Cosmopolitan article by Raymond Chandler. The renowned detective fiction writer listed Lonergan’s case as #9 in his list of the “10 greatest crimes of the century.” There have been a couple of novels based on the case and, writes Levine, “Over the years, the story of the murder, with the requisite number of theories about Lonergan’s sexual identity, has been told and retold in countless tabloid newspapers and magazines and remains a favourite topic of crime and mystery bloggers.”

Lonergan’s bisexuality plays an important part in the story, including his initial alibi, and Levine adds social context in this and other instances, such as describing the mores of the café society into which Lonergan married. Levine takes the tabloid aspect out of the telling, in that he seems to have harnessed the facts and his conclusion as to Lonergan’s innocence or guilt seems solid.

Rabinovitch’s ability to step back and tell the story of Wolfe Rabin in an apparently unbiased way is even more impressive, given that Rabin is his uncle. Granted, Rabinovitch never met Rabin, but still, family is family.

Rabinovitch’s ability to step back and tell the story of Wolfe Rabin in an apparently unbiased way is even more impressive, given that Rabin is his uncle. Granted, Rabinovitch never met Rabin, but still, family is family.

“How did my father’s brother, raised in an immigrant Jewish family in a remote Canadian prairie town [Morden, Man.], become a jukebox tycoon, a crony of gangsters and the mastermind behind an audacious and complex international money-laundering scheme?” writes Rabinovitch. “My investigation would reveal his world and a tale of jukeboxes, money laundering and organized crime.”

Rabin was a smart, creative and resourceful person. “He invented the car radio. He was a wartime profiteer. He designed the first jet-age jukebox. He was an international bonds trader,” writes Rabinovitch. “Wolfe and his sexy wife Trudy were a glamorous couple.”

But, early in his career, Rabin makes a deal with the proverbial devil, a mobster, and it’s a deal that makes him rich at first. But a competitor – fellow Manitoban David Rockola – successfully sues for patent infringements in the late 1940s, putting Rabin out of business and in need of money to pay back his criminal investors. It is fascinating to read of the mob connections to the jukebox industry, an industry that pulled in millions a week because, as Rabinovitch writes, “Even at the nadir of the Depression, anyone could afford a nickel for a song.”

And Rabin’s story becomes even more incredible after his jukebox business fails. In pursuit of much-needed cash, he becomes involved with stolen bonds, in what the U.S. Department of Justice called “the largest money-laundering scheme in history.” Eventually, the law does catch up with Rabin and some of his associates. Jail time is served. But Rabin’s biggest secret was only revealed long after his death in 1967, after Rabinovitch completed the draft of this book. It is one of the sadder elements of Rabin’s story. Despite all his achievements, there is much Rabin missed out on in his quest for wealth.

The Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival runs Feb. 10-15. For tickets, visit jccgv.com/jewish-book-festival.