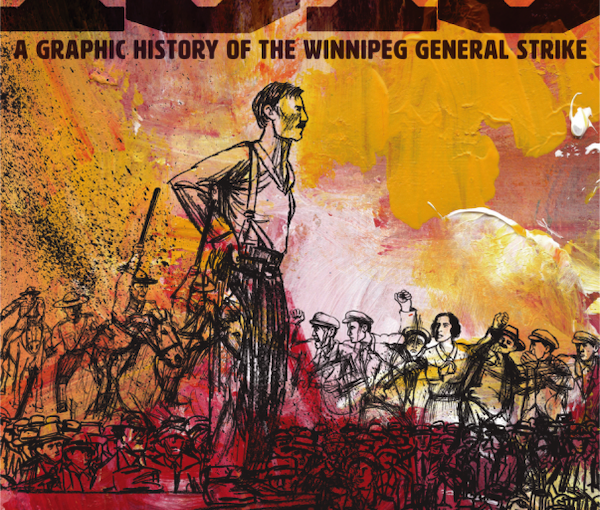

The book 1919: A Graphic History of the Winnipeg General Strike by the Graphic History Collective and artist David Lester is not education for education’s sake, but rather a “useful organizing tool,” according to the preface. “This comic book revisits ‘the workers’ revolt’ in Winnipeg to highlight a number of important lessons that activists can lean on and learn from today as they fight for radical social change,” notes the collective.

Lester, a Vancouver-based illustrator, musician, and graphic designer and novelist, will give the talk Getting Graphic with Labour History on June 7, 7 p.m., at the B.C. Government and Service Employees’ Union Lower Mainland Area office. He will also give a presentation as part of the World Peace Forum Society event 100 Years After the Winnipeg General Strike, in which Jewish community member Gary Cristall (activist and grandson of a 1919 solidarity strike activist) and others will participate on June 8, 2:30 p.m., at SFU Harbour Centre, Room 7000. In addition, he and members of the collective are participating in a few panels at the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences (congress2019.ca), taking place at the University of British Columbia June 1-7, and are then heading to Cumberland, B.C., for a June 23 event during the Miners Memorial Weekend.

In the Acknowledgements section of 1919, the Graphic History Collective describes itself as “a not-for-profit arts collective. For us, solidarity is not just a winning strategy in class struggle. It is our artistic methodology. In taking seriously the idea that we can accomplish more by working together, we prioritize collaboration…. As GHC members, we volunteer and share our artistic vision and share our artistic, writing and administrative skills.” The collective recognizes the many people who “contributed knowledge, labour and funding to this project. Most importantly, we recognize that this comic book would not have been completed without David Lester’s incredible talent and artistic labour.” Other GHC members who contributed are Sean Carleton, Robin Folvik, Kara Sievewright and Julia Smith; Prof. James Naylor of Brandon University’s history department wrote the book’s introduction.

“In 1919, 35,000 workers in Winnipeg, Manitoba, staged a six-week general strike between 15 May and 26 June,” the narrative begins. Lester’s two-page depiction of the strikers gathering at Portage and Main gives an idea of the vastness of the protest and the small area within which it took place. It is easy to see how people would have had nowhere to run and the panic that would have ensued when the Royal Northwest Mounted Police and the “special constables,” violently broke up the strike on “Bloody Saturday,” June 21, 1919. The police were among those who had voted to strike but were given dispensation to work by the strike committee; however, the city dismissed the whole force on June 9. The mayor, the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand (formed of business leaders and others) and the federal government opposed the strike and worked together to end it by various means, using fear of immigrants (aka racism) and eventually violence to do so.

1919 gives a history of the pivotal event from the perspective of the strike leaders, workers and their supporters. The textual narrative drops away, for the most part, in the telling of what happened on Bloody Saturday and the impact of Lester’s images builds as the day progresses, from 9:30 a.m. to 11, to 2:20 and so on. Just before 3:35 p.m., two strikers are shot, one dies on the spot, the other from gangrene. The violence continues. At 4 p.m., the special constables take control. By 6 p.m., Canadian Army Service Corps trucks – equipped with machine guns – are patroling Main Street. By the end of the day, in addition to the two strikers killed, many are wounded and 94 people are arrested. The book then describes some of what happened in the trials that followed, and the strike’s legacy.

Lester shares some of his artistic process and inspiration in the essay “The Art of Labour History,” especially the Bloody Saturday pages, and this is followed by a photo essay called “The Character of Class Struggle in Winnipeg.” The notes are useful in providing context for some of the images, and the bibliography shows the depth of research. Short bios of the contributors and a list of the Manitoba unions that supported the publication conclude the book.

“Art bears witness to the injustices of the world and, in reflecting on the pain and struggles of the past, offers hope in working together for a better present and future,” writes Lester. “Art can aid the momentum of progressive social change, and that is what keeps me going…. I am trying to capture and convey the inspiration and spirit of solidarity in class conflict. That is the art of labour history.”