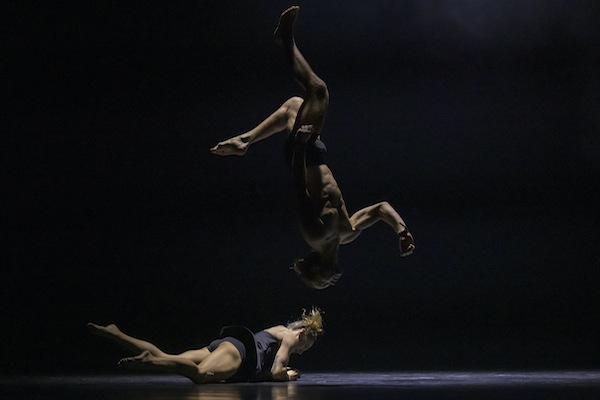

Juan Villegas rehearsing Edictum, choreographed by Vanessa Goodman, which is about Villegas’s Sephardi ancestry. The work is part of Dancing on the Edge’s EDGE One July 6 and 8 at the Firehall Arts Centre. (video still from Vanessa Goodman)

“I am very happy to be able to share my work and talk about Sephardic Jews, as I am doing a lot of research and I am discovering a lot about my own culture and where it comes from,” Juan Villegas told the Independent about Edictum, a new work with Vanessa Goodman about his family heritage, an excerpt of which he will perform at this year’s Dancing on the Edge July 6 and 8. “Throughout history, the Jewish community has suffered a lot and I am very happy to be able to pay respect, honour, shed some light and help tell the story of my ancestors,” he said.

Villegas and Goodman had already started their collaboration when Villegas found out that his ancestors were Spanish Jews who, following the Alhambra Edict of Expulsion in 1492 and the persecution of Jews by the Spanish Inquisition, sought refuge in Colombia.

In 2015, Spain passed legislation to offer citizenship to members of the Sephardi diaspora, but the window of opportunity to apply was only a handful of years and Villegas’s family missed it. However, they did apply to Portugal, which passed a similar law, also in 2015. Given the number of applicants, it could be several years before the family finds out. For the application, certified records were needed, so Villegas’s siblings hired a genealogist.

“They did both of my parents’ family trees and both ended up having the same ancestor – Luis Zapata de Cardenas, who came to Antioquia, Colombia, from Spain in 1578 and whose family had converted to Catholicism in Spain,” he said. “What is unclear to me is whether Luis Zapata de Cardenas was a practising Jew and was hiding it or if his family back in Spain became Catholic and raised him Catholic. I find it very hard to believe that people fully converted to Catholicism, as religion is so embedded in one’s culture and must be very difficult to switch by obligation. So, this is probably when they started disguising some Jewish rituals as Catholic, which happened a lot in Colombia.”

Villegas left Colombia in 2003, at the age of 18, concealing from his family his real reasons for leaving.

“I told them that I was going to only be in Canada for eight months to study English and then come back to Colombia,” he shared, “but deep inside I knew that I wanted to find a way to stay in Canada. I am gay and had a hard time growing up in Colombia – without realizing it, I was also escaping from a traumatic childhood, as I had been sexually abused and bullied at school. I was lucky enough that my parents helped pay for ESL studies in Canada and then I was able to do my university studies in Vancouver at Emily Carr University.”

After getting a bachelor’s degree in design from Emily Carr, Villegas worked at a design studio but was let go when the economy collapsed in 2008. He took about a year to figure out what he wanted to do next.

“I had a lot of unresolved trauma and I think it was a combination of having the time and (unconsciously) wanting to be healed from trauma that I started taking yoga and dance classes,” he said. “I met a dance artist named Desireé Dunbar, who had a community dance company called START Dance and she invited me to join her company. Vanessa [Goodman] had just graduated from the dance program at SFU and she was in the company also, this was back in 2009. Then, in 2010, I joined the dance program at SFU and Vanessa came to choreograph for us a couple of times. I always loved working with her and I felt like I connected with her.”

Graduating from SFU with a diploma in dance, Villegas moved to Toronto, where he danced for a few years. When he returned to Vancouver in 2017, he started following Goodman’s work. Intrigued, he asked if she would choreograph something for him and she agreed.

“And that piece that we created was about family,” he said, “but we left it at that, because I did not get the grants I needed to continue the work. So, when I discovered about my Sephardic Jewish ancestry, I pitched the idea to her and she agreed (without me knowing that she also has a Jewish background).”

Everything fell into place, he said, including some funding, so they took up work again this year on Edictum, which is Latin for order or command. The project was always intended to be a solo for Villegas, and they had started by “diving into his family history and the names of his ancestors to build movement language,” said Goodman.

“Since his family found that they have Jewish ancestry and were a part of the diaspora from Spain and Portugal in the 1400s, we found it very relevant to revisit the starting material and expand on this history inside the work,” she said. “I was raised Jewish culturally and we found, through conversations about our family rituals in relation to culture, food and celebration, there were some very interesting links between his family’s expressions of their identity and mine. We have woven these small rituals into the piece and have found a very touching cross-section of how this can be shared through our dance practice in his new solo.”

Goodman is also part of plastic orchid factory’s Ghost, an installation version of Digital Folk, which will be free to visit at Left of Main July 13-15. It is described on plastic orchid factory’s website as “a video game + costume party + music and dance performance + installation built around the desire to revisit how communities gather to play music, dance and tell stories.”

“I began working with plastic orchid factory on Digital Folk in the very early days of its inception,” said Goodman. “James [Gnam] and Natalie [Purschwitz] began researching the work in 2014 at Progress Lab, and I was a part of that initial research for the piece. Since then, the work has been developed over a long period of time with residency creation periods at the Cultch, at Boca del Lupo, at the Shadbolt, at SFU Woodward’s, and it has toured Calgary and northern B.C. This work lives in several iterations, but the Ghost project is a beautiful way for the work to live in a new way one more time. The cast got together at Left of Main in December of 2022 and filmed the piece for this upcoming iteration…. It is exciting to see a work have such a rich life with so many incredible artists who have been a part of this project.”

Dancing on the Edge runs July 6-15. It includes paid ticket performances at the Firehall Arts Centre, where Edictum will be part of EDGE One, and offsite free presentations, such as Ghost. For the full lineup, visit dancingontheedge.org.