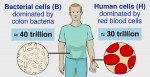

How many microbes inhabit our body on a regular basis? For the last few decades, the most commonly accepted estimate in the scientific world puts that number at around 10 times as many bacteria as human cells. In research published earlier this year in Cell, a recalculation of that number by Weizmann Institute of Science researchers reveals that the average adult has just under 40 trillion bacterial cells and about 30 trillion human ones, making the ratio much closer to 1:1.

The bacteria living in our bodies are important for our health. The makeup of each person’s microbiome plays a role in both the tendency to become obese and in each individual’s reaction to drugs. Some scientists have begun referring to it as the “second genome,” recognizing that it needs to be taken into account when treating patients.

The rising importance of the microbiome in current scientific research led the institute’s Prof. Ron Milo, Dr. Shai Fuchs and research student Ron Sender to revisit the common wisdom concerning the ratio of “personal” bacteria to human cells. Their research was undertaken as part of their work for the book Cell Biology by the Numbers, which was recently published by Milo and Prof. Rob Philips of the California Institute of Technology.

The original estimate that bacterial cells outnumber human cells in the body by 10 to one was based on, among other things, the assumption that the average bacterium is about 1,000 times smaller than the average human cell. The problem with this estimate is that human cells vary widely in size, as do bacteria. For example, fat or muscle cells are at least 100 times larger than red blood cells, and the microbes in the large intestine are about four times the size of the often-used “standard” bacterial cell volume. The Weizmann scientists weighted their computations by the numbers of the different-sized human cells, as well as those of the various microbiome cells. They also weighted their calculations for the quantities of “guest” bacteria in different organs in the body. For example, the bacteria in the large intestine dominate, in terms of overall numbers, all the other organs combined.

* * *

Feeling sick is an evolutionary adaptation, according to a hypothesis put forward by Prof. Guy Shakhar of the Weizmann Institute’s immunology department and Dr. Keren Shakhar of the psychology department of the College of Management Academic Studies, in a recent paper published in PLoS Biology.

We tend to take it for granted that infection is what causes the symptoms of illness, assuming that the microbial invasion directly impinges on our well-being. In truth, many of our body’s systems are involved in being sick: the immune system and endocrine systems, as well as our nervous system. Moreover, the behavior we associate with sickness is not limited to humans. Anyone who has a pet knows that animals act differently when they are ill. Some of the most extreme “sickness behavior” is found in such social insects as bees, which typically abandon the hive to die elsewhere when they are sick.

The symptoms that accompany illness appear to negatively affect one’s chance of survival and reproduction. Symptoms, say the scientists, are not an adaptation that works on the level of the individual. Rather, they suggest, evolution is functioning on the level of the “selfish gene.” Even though the individual organism may not survive the illness, isolating itself from its social environment will reduce the overall rate of infection in the group.

In the paper, the scientists go through a list of common symptoms, and each seems to support the hypothesis.

Appetite loss, for example, hinders the disease from spreading by communal food or water resources. Fatigue and weakness can lessen the mobility of the infected individual, reducing the radius of possible infection. The sick individual also can become depressed and lose interest in social and sexual contact, again limiting opportunities to transmit pathogens.

The scientists have proposed several ways of testing the hypothesis, but they hope its message sinks in: when you feel sick, it’s a sign you need to stay home. Millions of years of evolution are not wrong.

For more, visit wis-wander.weizmann.ac.il.