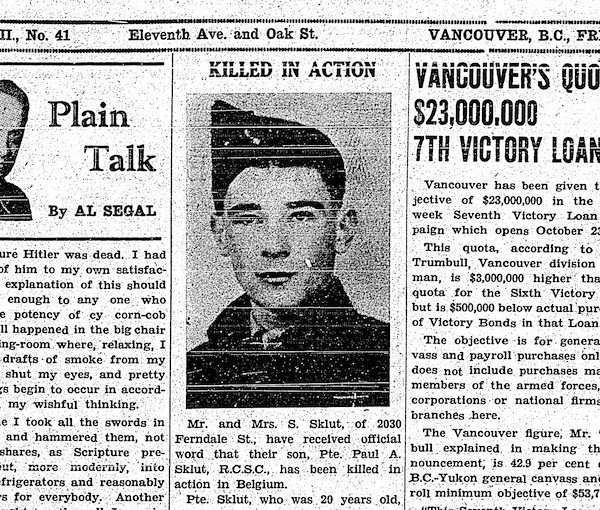

Dr. Ilona Shulman Spaar moderates a panel with Holocaust survivors, left to right, Janos Benisz, Amalia Boe-Fishman, Dr. Peter Suedfeld and Alex Buckman. (photo by Pat Johnson)

One survivor of the Holocaust who spoke at a panel recently believes that, in a generation or two, people will largely forget about the catastrophic events of that time.

“I think the world will forget about Auschwitz,” said Dr. Peter Suedfeld, a professor emeritus in the department of psychology at the University of British Columbia. “The world has already forgotten about ‘never again.’ We’ve had a fair number of genocides since 1945, in which the world did not intervene. A recent poll that I saw … apparently, the proportion of people who remember anything about how many Jews were killed in the Holocaust, what Auschwitz was, what the Holocaust was and so on, is not all that much above 50%.

“This is going to go on generation after generation,” he continued. “The survivors won’t be here to push the story any further. Their children will for awhile, but they have other things to do and other things to be concerned about and their children even more so. In a few more generations, it will be in the history books and people will say, yeah, I read about that or thought about that in grade whatever but, in terms of remembering it as something in your gut, something that arouses an emotion, something that has a personal connection to you, I don’t think it’s going to last all that much longer. I’m sorry to say that, but that’s what I think.”

Suedfeld, who weeks earlier was invested into the Order of Canada for his decades of work on the psychological and physical effects of extreme and challenging environments, was speaking at Hillel House, on the UBC campus, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27. He was part of a panel of four survivors sharing their reflections 75 years after liberation.

Suedfeld, who was born in Hungary, survived under false papers and a back story as an orphaned Roman Catholic child. He recalled successive bombardments of the various sanctuaries he was in near the end of the war, as Allied bombers repeatedly blew buildings apart while Suedfeld and other children hid in the cellars.

After liberation by Russian forces, Suedfeld was eventually reunited with his father; his mother had been murdered. The lesson he took from the experience, he told the packed afternoon audience, was to cherish and defend the values of freedom.

“Freedom to be who you really are, but freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of religion, freedom of everything,” he said. After moving to the United States, Suedfeld became a powerful advocate of the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of religion and expression. Since coming to Canada, he has been a similar champion of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, he said.

Suedfeld’s admittedly pessimistic perspective on the future of Holocaust remembrance was contested by Alex Buckman, a fellow survivor on the panel.

As long as organizations exist like the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, which co-sponsored the event with Hillel BC, and children of survivors and others who have been touched by their experiences share the lessons they have learned, the future will be better, he said.

“Maybe our children will pick up, speaking on our behalf,” said Buckman. “Maybe they will remember because we will tell them what happened.”

Like Suedfeld, Buckman survived by being hidden by Catholics; in his case, in Belgium.

“They told us that the war was over and that we should rejoice and be happy and our parents would come and pick us up and everything would be hunky-dory,” he recalled. “At 6-and-a-half in an orphanage, nothing was that rosy. We saw parents come and pick up their children and take them home, but nobody came for us. I was there with my sister Annie and she was crying and wondering why our parents weren’t coming and I tried to tell her that I’m sure that they will come. But, like her, I didn’t know why they weren’t coming.”

The pair were moved back to Brussels and put in the care of the Red Cross, which posted the names of orphaned and unclaimed children on sheets around the city. Eventually, a paternal uncle showed up and took the two children to Annie’s parents – who, since little Alex had believed himself to be Annie’s brother, he reasonably concluded were also his parents. The truth came out in a cruel way, when another cousin, in a pique of anger, blurted out to Alex that his parents were dead and that Annie’s parents were not his.

“I took a step back and, for the first time, I realized I was alone,” Buckman recalled. His aunt and uncle did care for him, though, despite the uncle’s misgivings, because of the aunt’s insistence based on a promise she made to the heavens when she learned of her sister’s death.

Also on the panel was Amalia Boe-Fishman, who was born in the northern Netherlands in 1939 and also survived thanks to a Christian family. Like many survivors, her liberation story is not one of joyous freedom but of confusion and fear of the future.

“Liberation should have been a real happy time for me. It wasn’t,” she said. “I was told we were free, but what did that mean? What did that mean to a frightened 5-year-old girl who had been in hiding for three years? What did it mean to be free? I was told that, for the first time I could remember … I would now be able to go outdoors. I didn’t know what to expect. What was there? What was waiting for me outdoors? Indoors had become my entire life. Indoors was where I felt secure and safe. Indoors was all I knew.”

Her first venture out was harrowing. It was odd enough to be surrounded by throngs of strangers after her entire life had been confined to just a few familiar faces. After a victory parade, the girls she knew as her “sisters” decided to walk to the town centre. While crossing a bridge with scores of others – Amalia had never seen a bridge before – a rumour started that the Nazis had returned and panic swept the crowd. Pushing and shoving was accompanied by screaming and concern that the bridge was about to collapse.

“Here I was, trapped outdoors, in a crowd of panicked strangers and I was terrified,” she said. “The bridge didn’t collapse, but, as you can imagine [it was] a very long time before I would ever cross a bridge again.”

Another ostensibly joyous aspect of liberation was also clouded with confusion and fear.

“I was told that I had a real family. I had a real father, a real mother, an older brother and a baby brother,” said Boe-Fishman. “Miraculously, out of many different hiding places, all four of them had survived the war.… But who were these people? They were strangers. So, this is what liberation means to me. To leave the only family I ever had known to go outdoors to a place of terrified strangers, to strange people in a strange home.… I had to adapt to a new and also frightening world.”

For Janos Benisz, liberation was similarly conflicted. As a child, he had seen his father and his grandmother dead in the streets. His mother had been killed earlier by Nazi collaborators, during what was to have been a routine medical procedure.

Young Janos was transported from his hometown of Esztergom, Hungary, to Budapest, where Jews were divided up, many being sent directly to death camps including Auschwitz.

“I ended up in an Austrian slave labour camp,” he said, remaining there for seven or eight months before the Russians liberated them.

“I had the body of a 4-year-old,” he recalled. “At my bar mitzvah, I was under five feet.”

Making his way back to his hometown, he found squatters in the family’s house and learned that, of his immediate family of eight uncles, two aunts and 29 cousins, only Janos and one uncle had survived the Nazis.

Benisz was put in a Jewish orphanage in Budapest, then sent to Halifax, where he was put on a train to Winnipeg. He was bounced from foster home to foster home, back to an orphanage and then to a reformatory.

“I couldn’t fit in,” he said. At 18, he got a job at the Winnipeg Free Press as a copy boy.

“I spent the next 15 years in the newspaper business, then I became a salesman on my own, retired in ’71,” he said. He noted the figurative and literal centrality of the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver in his life today. He lives 40 yards from the centre, he said, and much of his social life is focused there.

“It’s my second home,” he said. “I work out there. I shmooze there. I’ve got a group of guys I call the ‘kosher nostra.’ I’m very happy. I absolutely adore this country of Canada. It’s been good to me ever since I turned 18.”

Prior to the panel, Holocaust survivors lit candles of remembrance. Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart read a proclamation declaring International Holocaust Remembrance Day in the city. Rob Fleming, British Columbia’s minister of education, spoke on the importance of Holocaust education and credited the partnership of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre (VHEC). Student Adam Dobrer shared his family’s Holocaust legacy. Prof. Nancy Hermiston, director of voice and opera at the University of British Columbia, provided opening remarks. Nina Krieger, executive director of the VHEC, introduced the program and spoke of the importance of remembrance and the power of the memory of Auschwitz on the 75th anniversary of its liberation. Dr. Ilona Shulman Spaar, education director and curator of the VHEC, moderated the panel. Rabbi Philip Bregman, chaplain of Hillel BC, chanted El Maleh Rachamim and the Mourners’ Kaddish.

Many other commemorations and events took place throughout the province on and around Jan. 27.