Michelle Valenzuela, centre, along with her brother, Pedro de Jesus Valenzuela Mora, and mother, Diana Mora. (photo from Michelle Valenzuela)

Almost 500 years after her Sephardi ancestors were forced out of Spain, Michelle Valenzuela is on a path back.

The 28-year-old artist and art teacher from Colombia is currently living and studying in Vancouver as the Spanish government finishes processing her citizenship application along with one from her brother. Their mother is pursuing a similar process with Portugal after both countries opened their doors to the descendants of Sephardi Jews persecuted during the Inquisition.

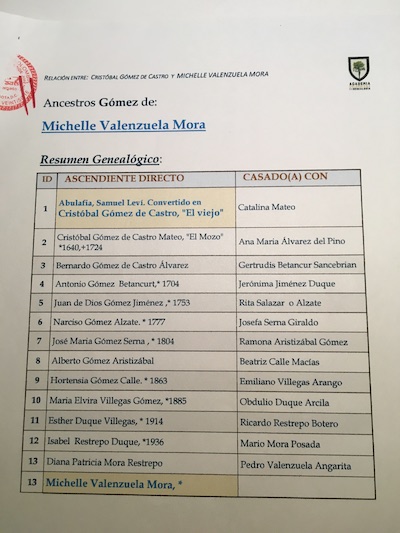

Growing up in a deeply Catholic family, Valenzuela had no inkling of a Jewish heritage until a cousin who works at the Colombian Academy of Genealogy told them what he had discovered: their family descended from Samuel Levi Abulafia, who had adopted the Christianized name of Cristobal Gomez de Castro before being expelled from Spain in 1570. He had been found guilty of sacrilege, bigamy, heretical ideas and promoting Judaism.

“We found out the Jewish background of our family story,” Valenzuela told the Independent. “For me, it was shocking. I don’t have a good relationship with Catholicism so I always felt like the black sheep of the family. It was an explanation for myself that our origins weren’t that Christian.

“There’s something particular about my mother’s family, the whole personality of the family, which is really different from other cultures in Colombia.”

Her grandmother, for instance, started a successful business that still exists, unusual at a time when most Latin American women were expected to stay home and care for children.

Although her cousin had earlier discovered the Jewish origins, he didn’t tell the rest of the family until after Spain passed legislation in 2015 to offer citizenship to members of the Sephardi diaspora.

“I think it’s related with the fact that the family became really Catholic and proud of being Catholic. One of his brothers is a priest,” explained Valenzuela.

Jews who came to Colombia hundreds of years ago had to hide their faith because the colonies of Spain carried out their own inquisitions.

As Sephardi people spread to all corners of the earth, the largest communities were established in Israel and Turkey, followed by the colonial holdings of Spain and Portugal in the New World. The expulsion of Jews followed Spain’s campaign to also rid the country of followers of Islam, known as Moors.

The 2015 law is aimed at historical redress for the descendants of about 160,000 Jews expelled on the 1492 orders of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. About 100 years later, another 300,000 Jews who had converted to Catholicism, but nonetheless incurred the wrath of Spanish authorities, were also expelled – including Valenzuela’s ancestor.

Remarkably, documents from the hearings that forced people into exile are accessible online due to digitization of the Catholic Church’s records.

Now, her parents face the knowledge that the church they serve – her mother as a Bible teacher and her father as a deacon in training – is the same one that forced her ancestors to convert or flee.

“I tried to ask [my mother] about her thoughts about her family being Jewish and I think she’s not able to confront it,” Valenzuela said. “Her answers are vague, evasive. I think she’s surprised as well with her Jewish roots, but she has always referred to the Jewish people as older brothers to the Christians.”

Accountant to the king

Research into the family’s roots in Spain and Portugal also led to a much more famous Samuel Levi Abulafia, a 14th-century advisor and treasurer to Pedro I, the king of Castile and Léon.

Abulafia was prominent between about 1320 and 1360, first as an aide to Portuguese nobility and ultimately as a wealthy and powerful official in Toledo, where Abulafia commissioned construction of El Transito Synagogue on a street now bearing his name and statue. His nearby former palace in the city’s Jewish Quarter now houses a museum of El Greco’s paintings.

Also known as Samuel ben Meir Ha-Levi Abulafia, he fell out of favour with the king as anti-Jewish sentiment grew in the Late Middle Ages. Accused of disloyalty to the king, he was imprisoned, tortured and killed in 1360 and his assets seized by the crown.

The synagogue was converted to a Catholic Church and declared a national monument in 1877. It has since been restored as a synagogue and now includes a Sephardi museum.

Applying for citizenship

The process to gain citizenship is long and costly, requiring money and persistence to complete. Even now, two years after the deadline for applications closed in Spain, Valenzuela and her brother are waiting for final citizenship documents to arrive.

Files received by the 2019 Spanish deadline are still being reviewed, while a similar program in Portugal continues to accept applications.

About 132,000 have applied to the Spanish program and at least 34,000 new citizenships have been granted so far. Most have come from Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia, according to news reports. The program began refusing a high number of applications in 2019, saying that fraudulent cases were on the rise.

Even before the Spanish bureaucracy considers the evidence, the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain, along with a Jewish community in countries of origin, must approve the application. Then, there is the need to show a “special connection” to Spain, which the Valenzuela family fulfilled by contributing to the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in Bogota. Applicants must also speak Spanish.

There is no requirement to be a practising Jew or give up citizenship from their home country.

New possibilities

It’s not lost on Valenzuela that the process brings cash into Spain – a 100 euro application fee, about 600 euros for notarizing original documents delivered in person to Madrid and another 80 euros to write a test on knowledge of Spanish history, society and culture. Applicants also travel to Spain at their own expense, putting it far out of reach for many applicants from Latin American countries with high unemployment and weak currencies.

It means successful petitioners will have both money and education. And many are young, bringing the possibility of adding new workers to an aging country. United Nations data indicates 10% of the Spanish population was over 60 in 1950, but that will rise to 30% in 2025.

For Valenzuela and her partner, Carlos Perdomo, a lawyer from Colombia working in Vancouver, proving Jewish roots in Spain is another chance at finding a way out of the economic difficulties in their home country. They are both also permanent residents of Canada.

“We wanted to improve our possibilities for the future [outside Colombia],” she said, and obtaining a European Union passport should help.

“It’s so great to know more about your family and have a material link. We would love to use it, maybe for a master’s degree in the future. It would be cheaper and easier for me to travel there, having citizenship.”

Valenzuela says her trip to Spain in December was her first and she was surprised at how much it is like Bogota: disorganized, loud and crowded.

“Being a Colombian is always linked to the notion that Europeans are better in every way. It’s easy to romanticize and idealize Spanish culture and art, but the reality is we’re very similar.”

Erin Ellis is a former newspaper reporter and copy editor for the Edmonton Journal and Vancouver Sun. She also contributes to Canada’s National Observer and CBC News. She’s keenly interested in history and loves telling people’s stories.