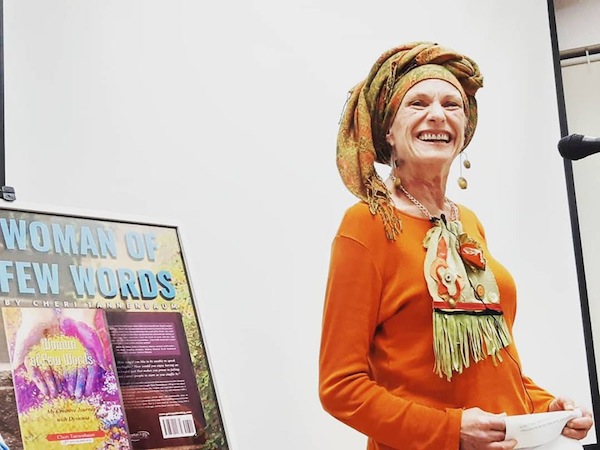

Artist Amy J. Dyck sits amid her work “Bed Desk,” one of the pieces in her solo exhibit, Portals to Elsewhere, which opened at the Zack Gallery last month. (photo by Byron Dauncey)

The art of Amy J. Dyck is surreal and enigmatic. Her solo show Portals to Elsewhere opened on Aug. 25 at the Zack Gallery. Like any portal, it allows a viewer a glimpse into the artist’s sophisticated and contradictory inner world.

“I loved drawing when I was young,” Dyck said in an interview with the Independent. “I liked little details: earrings, shoelaces. It was easy, like a game. Then I had a son and, like every young mother, I was always tired. Creating art at that point stopped just being fun. I needed to concentrate, to find time for my art, to figure out whether I wanted to spend that time. That was when I became a real artist.”

That wasn’t the only time life challenged her. “I wanted to be a designer,” she said. “I started at design school but, after one year, I became too sick and had to drop out.”

But she never abandoned learning – she taught herself, read textbooks and took occasional classes. And she never stopped creating – paintings and drawings, mixed-media collages and soft sculptures, ceramics and wood installations dominated her life, as she juggled being an artist with her non-artistic jobs, family and chronic illness.

Multilayered and metaphorical, Dyck’s collages and sculptures could be seen as a self-portrait of an artist battling a chronic disability.

“I’m often sick and can’t move much,” she said. “Sometimes, I spend several months in bed. That’s why I make soft sculptures. It’s easier when I’m in bed and can’t go to my studio. I have to be flexible with my materials and techniques to accommodate my illness.”

Despite the hardships associated with her ill health, Dyck’s works don’t display any bitterness or resentment. Instead, the artist is on a journey of self-discovery.

“I have to learn how to live in a body that’s broken,” she explained. “That’s what my art is about. My soft pieces are something I want to wrap around myself, to counteract my anxiety.”

All the sculptures on display at the gallery present complex knots of fabric, pipes stuffed with soft fillings. Combined with ceramic elements, leather, wood, feathers and other materials, these ouroboros reflect the artist’s struggles and her determination to live as fully as she can. Her philosophical piece “Blame Mosquito” is a fur ball with half a dozen ceramic hands coming out of it, pointing in all directions. “When I was young,” she recalled, “there was a traumatic event in my life. I blamed everyone – like those fingers pointing everywhere – until I realized that I myself carried some of the blame. That’s why one of the hands points back at me.”

“Yellow Polka-dot Tail” also has sharp, dark spikes coming out of the soft, colourful tangle and pointing everywhere. “Those spikes are like my anger. They help me feel powerful,” she said.

Another piece, “Wing Head,” introduces a strange single wing decorating the sculpture’s head. “The wing is not functional,” she said. “Just like parts of my body. It is a possibility of flight, an idea, not a reality.”

Dyck explores a body that doesn’t work well by creating allegorical figures with faulty anatomy, with the wrong number of fingers on a hand or mangled joints or tiny wings in the wrong places. “I’m processing my disability through symbolism,” she said.

She uses second-hand materials for her sculptures. “I buy old clothing at thrift stores or internet marketplaces. The leather came from our old couch. My kids helped me dismantle it and cut out the pieces I could use,” she said.

The theme of a body disrupted, of limbs disconnected, continues in her painting-like mixed-media collages. Many of them have images of open doors, windows or arches. “They are my portals to elsewhere,” she said. “When I’m in bed, when I can’t move, I look out of my window and imagine myself out there. I like being outdoors.”

The images are uncomfortable and deformed, but there is optimism, a strange equilibrium of what might be considered ugly and beautiful. Body parts surrounded by butterflies. Too many hands counterbalanced by birds and ghosts, black and white charcoal drawings incorporating splashes of real gold. All of them speak of a deep need to understand our own bodies, how they work and why they sometimes don’t. The style of the artist is unique and instantly recognizable, and that is what Dyck teaches aspiring artists – she offers classes at community centres and retirement homes. “I try to teach my students how to find their own voices,” she said.

One of the most interesting examples of Dyck’s art is an installation called “Bed Desk.” Dyck explained its etymology.

“I promised the gallery a sculptural installation, but then I became very sick and couldn’t leave my bed,” she said. “My husband is a builder. He made those wooden stands that surround the circular space and act as frames for my drawings. He also made me a bed desk where I could draw while in bed, but I could only create pieces of the same shape and size as the desk surface. I channeled my longing to move, to feel strong into those drawings. The figures I drew are broken, like me, but they move, they grow, they adapt and evolve. The installation was funded by a Canada Council for the Arts grant. When you step into its circle to view the drawings, you enter your own portal to elsewhere.”

Dyck’s show will be at the Zack Gallery until Oct. 1. To learn more about the artist and her work, visit her website, amyjdyck.com.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at olgagodim@gmail.com.