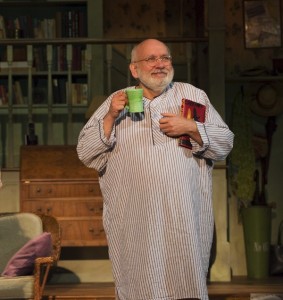

Robert Salvador, left, Anna Galvin and Jay Brazeau in Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike. (photo by David Cooper)

Ah, the trials and tribulations of brothers and sisters. It’s the few and far between who go through life without the experiencing them. But, as with all humans, the beauty of the sibling dynamic is that just when you think you know someone, they turn around and surprise you. They show a vulnerable side you never thought existed; come through in the crunch to do the right thing; or push you out of your comfort zone, enabling you to discover a life you didn’t think you could have.

Such is the story of Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike, a wonderful play by Christopher Durang that retells the story of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya in a contemporary setting.

In the modern-day version, rather than uncle and niece, Vanya (Jay Brazeau) and Sonia (Susinn McFarlen) are a brother and adopted sister left behind to look after ailing parents, while sister Masha (Anna Galvin) – representing Chekhov’s Prof. Serebryakov – has taken off to become a world-famous movie star. She gave up being a respected stage actress and is now known for playing a nymphomaniac serial killer in Sexy Killer, which has spawned five sequels.

Their parents, fans of Chekhov, gave them all names from the Russian’s works. In a nod to Uncle Vanya, the parents left the house to Masha, who hardly ever visits and has only come back this time to sell the home in which her brother and sister live, which would leave them homeless.

In Uncle Vanya, the professor arrives with a much younger second wife; in Vanya, Masha arrives with Spike (Robert Salvador), a much younger and even more self-absorbed male co-star. Masha flounces about the stage, callously rubbing her siblings’ noses in her successes and boasting about her studly lover, while Vanya and Sonia berate her for being absent when her parents were ailing and wallow in their own misery of unfulfilled lives.

Added to the mix is Cassandra (Carmen Aguirre), a clairvoyant who channels spirits, warning Sonia and Vanya of future evils. “Beware Hootie Pie,” she moans. “Beware of mushrooms in the meadow.” Her seemingly nonsensical visions turn out to have merit, although no one can actually interpret what she says in the moment for any practical purposes.

While the play has consistent overtones of regret, jealousy and disdain, it’s not without its humor, due largely to the quips between the homebound brother and sister.

“I had a dream that I was 52 and not married,” laments Sonia at the play’s onset.

“Were you dreaming in documentary?” Vanya retorts.

As well, Vanya, who is gay, draws many laughs from the audience as he ogles Spike, particularly during a hilarious “non” strip-tease sequence.

And while Masha starts off as the uncaring evil stepsister, who won’t even let Sonia talk, it’s pretty clear how unhappy she is after five failed marriages and having never gotten to play her namesake on stage.

In the evening, the three siblings (Vanya and Sonia, reluctantly) and Spike head to a costume party, where Masha hopes to meet a realtor who will sell the house.

Sonia takes the one opportunity she has to upstage her sister by dressing in a beautifully sequined gown.

After they return, Masha finds out she has lost Spike to a younger woman, but, in Cinderella fashion, Sonia has met a man at the party, opening up possibilities for romance. Using “voodoo,” Cassandra causes Masha to have a change of heart.

In the epilogue of the performance, Vanya is presenting a play that he wrote, only to have Spike disrupt the flow by checking his cellphone. This sends Vanya into a rant of how things used to be, much like Chekhov’s doctor in Uncle Vanya. He grieves over the loss of simpler times and fumes, “There are 785 TV channels. You could watch the news that matches what you already think!”

Director Rachel Ditor’s experience with the playwright goes back to when she performed in Durang’s Beyond Therapy, in 1980. She calls his writing “fabulously subversive and hilarious” and rightly points out that rather than being quelled by mainstream culture, it is the mainstream that has picked up on his theatrical cues.

From the moment Brazeau entered the stage looking like Rip Van Winkle in a three-quarter-length nightgown and let out a big yawn (as Chekhov directed Uncle Vanya to do), I knew this was going to be a good play. While the secondary roles were somewhat overacted, they were entertaining, nonetheless, and the poignant portrayals of Vanya and Sonia combine with a great script to deliver a thoroughly enjoyable play from start to end.

Vanya runs at the Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage until April 19.

Baila Lazarus is a freelance writer media trainer in Vancouver. Her consulting work be seen at phase2coaching.com.