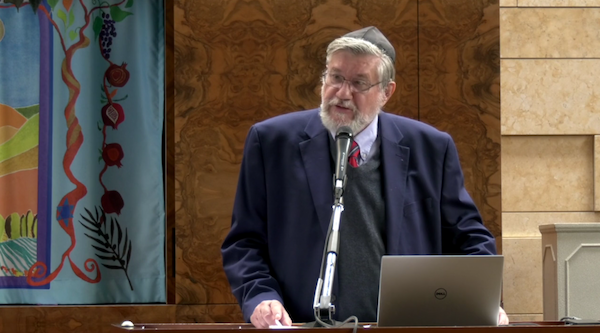

For 20 years, on the afternoon of Yom Kippur, Prof. Chris Friedrichs delivered a lecture to the congregants of Temple Sholom on the subject of the Holocaust. It started in 2004, when Rabbi Philip Bregman, now rabbi emeritus of the shul, asked Friedrichs to speak on the most solemn day in the liturgical calendar. The rabbi asked him to reprise the lecture the following year, and it became an annual event.

After the 2014 passing of Friedrichs’ wife, Dr. Rhoda Lange Friedrichs, like her husband an historian, Rabbi Dan Moskovitz announced that the presentation would be known as the Rhoda Friedrichs Memorial Lecture.

Friedrichs, now professor emeritus of history at the University of British Columbia, decided to end the tradition after 20 years and his friend and UBC colleague, Prof. Richard Menkis, suggested the idea of compiling the lectures in a book.

The volume, Reflections on the Shoah: Yom Kippur Sermons Given at Temple Sholom 2004-2023 is a small but irreplaceable volume offering deep and original insights on the lessons of history from a leading thinker on these subjects.

In these lectures, Friedrichs does not dwell on the facts of history so much as draw broader insights into their meaning. In 2005, he reflected on the term “martyrs,” which is often used in reference to the victims of the Nazis.

“A martyr is someone who has accepted death rather than renounce his or her Jewish faith,” he said. Yet, he noted, among the six million were many, like the Jewish-born Catholic nun Edith Stein, who were not killed because they refused to renounce their faith. Indeed, he said, renunciation would not bring redemption. It was Jewish “racial” identity, not adherence to Jewish ideas, that drove the Nazis’ murderous objectives.

In an historic sense, though, Friedrichs argues, Jews were murdered in the Holocaust because generations of ancestors had refused, against all pressures, to abandon their identities. “And, therefore, it is in fact right to honour those who died as martyrs,” he said.

In 2007, Friedrichs struggled with theologians’ explorations of the meaning of the Shoah, as though some divine purpose could be discerned from it.

“The Shoah was an entirely human event,” he said. “But that hardly removes the question: where was God while it took place? Why did God allow it to happen?”

God gave humans free will, he concluded, but this does not answer the unknowable question.

“In a world we cannot begin to understand, we can still hope for mercy, and we can pray for strength,” he said.

In a brief postscript to this lecture, Friedrichs writes that the daughter of a friend, having heard the sermon, asked her father “Where was God?” In response, the father said, “Where was man?”

In 2012, Friedrichs spoke of the first Holocaust memorial ever created, in May 1943, in the Majdanek death camp, where a group of prisoners persuaded the SS administrator that the camp could be made more beautiful if they could erect a pillar topped by a statue of three eagles about to take flight. The commandant never knew that under the base of the pillar the inmates had buried a container of ashes of the victims taken from the crematorium.

In 2013, Friedrichs addresses the problem with the very word Holocaust, which means a burnt sacrifice.

“What a meaningless term!” Friedrichs declared. “Six million Jews were sacrificed? Sacrificed to what God? Sacrificed to what end?”

In 2020, when his lecture was recorded and shared virtually because of the pandemic, Friedrichs spoke of the sanctity of life.

The next year, after unmarked graves were discovered adjacent to a former residential school in Kamloops, he spoke of the “humanitarian obligation to go beyond just our circle of Jewish concerns.” He drew parallels between the MS St. Louis, the ship of Jewish refugees turned away from ports of refuge, including Canada’s, and the Afghans clambering through the Kabul airport, struggling to escape the country before the takeover of the Taliban.

In 2022, he invoked a very different piece of history. In high school, his most memorable teacher was Anne Schwerner. When the news came, in the summer of 1964, that three civil rights workers had been murdered by white supremacists in Mississippi, one of them Michael Schwerner, Friedrichs realized this was his favourite teacher’s son. He reflected on the lessons of obligation to universal freedom and rights embodied in Jewish tradition.

In his last lecture in the series, Friedrichs spoke of how, when he speaks to audiences of high school students, as he frequently does, he makes the lessons relevant to young, multicultural Canadians.

In his last lecture in the series, Friedrichs spoke of how, when he speaks to audiences of high school students, as he frequently does, he makes the lessons relevant to young, multicultural Canadians.

“I tell the students that it is normal to dislike somebody because that person, as an individual, is bad or unkind or unpleasant,” he said. “But to dislike or hate somebody not because of their own characteristics but because they happen to belong to a group, to hate them just because they are Chinese or Filipino or South Asian or Black or members of any other group, is to take the first step on a path that has led and could lead again to things like the Holocaust.”

In most of his lectures, Friedrichs describes predations that are difficult to read and must have been more difficult to hear on a Yom Kippur afternoon, in a room that includes survivors of precisely such atrocities. This, though, is one of the invaluable aspects of Friedrichs’ approach. Whatever reservations might exist in this time of safe spaces and trigger warnings, one can hardly make the case that it is too burdensome to listen to a few examples of the barbarism for the sake of education, memorialization and understanding, when there are people in our community, including in the congregation Friedrichs was addressing, who experienced the cruelties themselves.

Anyone who heard these lectures when they were delivered, or has heard any of Friedrichs’ many presentations elsewhere, can hardly help but hear his deep voice and commanding delivery while reading his words. Those who haven’t had the privilege of hearing him speak are fortunate to have these lectures compiled in this new book.

Reflections on the Shoah is available at templesholombc.shulcloud.com/form/reflections.