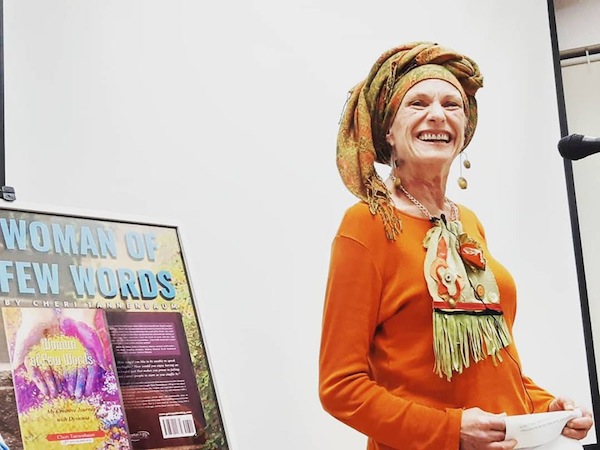

Author Cheri Tannenbaum gives a talk about her book, A Woman of Few Words. (photo from Gefen Publishing House)

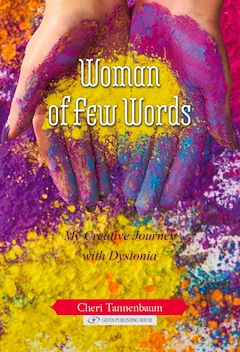

“Happiness is a choice,” writes Cheri Tannenbaum in her book Woman of Few Words: My Creative Journey with Dystonia (Gefen Publishing House, 2019).

No one would blame Tannenbaum for not being happy, for staying in bed, for giving up. But that’s not who she is. “From the first day of my illness to this very day,” she writes, “I wake up each morning, say Modeh Ani (the prayer said upon waking in the morning), push myself out of bed, and consciously and deliberately choose life.”

Born in Edmonton, Tannenbaum is the oldest child of Samuel (z”l) and Frances Belzberg; the family moved to Vancouver when she was 16. With refreshing honesty, Tannenbaum shares her struggles with anorexia, but also some of the ways in which she was a “happy, fun-loving, gregarious, outgoing flower child” when she was in her teens. She writes about how she became religious, and it is her strong belief in God that has buoyed her since she became ill with dystonia at the age of 20, the first sign of which was that her “handwriting suddenly became totally illegible.” As well, her voice became monotonic, and other symptoms appeared, including severe difficulties in walking and, eventually, speaking, a symptom that, very much later in life, was remedied, as the unexpected result of medication intended for another purpose.

Woman of Few Words details Tannenbaum’s life with dystonia, which, according to the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, which was founded by her parents, “is characterized by involuntary muscle contractions and spasms.” She openly talks about the time she attempted suicide and the difficulties she had in having children. She offers thoughts on living with the illness and lessons she has learned, as well as several pages on dystonia and many inspirational quotes from various sources.

Tannenbaum has a bachelor’s in psychology and a master’s in human development. She has followed her passion – art – in more than one creative direction. She has a long-lasting marriage, three children, grandchildren, and family and friends who care about her, and she has lived in several places in the world, making her home in Efrat, Israel. As she writes, “Dystonia is not my essence, nor does it define me.” It does, however, present many challenges.

“If I didn’t have the belief that there is an all-loving, all-powerful G-d who runs the world and has a master plan, then all challenges are just random; things that happen are just occurrences coming from nowhere…. Most probably, those challenges would feel meaningless and purposeless,” she told the Independent.

Tannenbaum responds to every reader who sends her a note. “The notes I have gotten have been extremely positive, telling me how I have helped them or given them a different perspective, etc.”

Tannenbaum responds to every reader who sends her a note. “The notes I have gotten have been extremely positive, telling me how I have helped them or given them a different perspective, etc.”

She said, “If I were to have gotten only one response that I have touched one person’s soul then I have accomplished what I set out to do – baruch Hashem, I have gotten more than one.”

Tannenbaum’s mother shared some of the ways in which her daughter’s illness affected the family.

“Cheri’s illness was slow in showing itself so, at first, her tripping or falling or dropping things was almost a joke for her siblings,” said Belzberg, who has three other children. “I took her to our family doctor, who said it was just teen angst, then that it was physiological, so she saw a psychiatrist, who said she was fine, so back to the GP.

“As her condition became worse, I began shopping for different kinds of medical advice locally and even to Scripps Clinic in California, and still no answers.

“In the meantime,” said Belzberg, “Cheri met Harvey, married and moved to Los Angeles … and her condition worsened.”

Belzberg said it took almost five years for them to get a diagnosis and a name for her daughter’s condition: dystonia muscular deformans. “There were, at that time, three known patients,” said Belzberg. “Today, we have several hundred on this continent alone.”

With no known patients and no known treatment or cure, Belzberg said, “My husband mobilized with the help of two doctors from UCLA [University of California, Los Angeles], Dr. John Menkes and Dr. Charles Markham; we gathered about five or six known neurologists from across the U.S. and began to do research. Meetings were set up for every two weeks and both my husband and I monitored the meetings between the experts … with the whole purpose of finding everything there was to know about the disease and how to treat it.

“Word got out that this was being addressed and there was more interest from within the research community,” she said. “We got a grant from the NIH [National Institutes of Health], plus our own … financial support, to establish ourselves, and began a series of research conferences with different doctors with different specialties. That was almost 40 years ago and, this June, there will be the Samuel Belzberg 6th International Dystonia Symposium in Dublin, Ireland, the latest in our international annual meetings.

“Through our persistence, as parents, we have created an international research body with a large patient list and researchers waiting to have their grants financed,” said Belzberg. “We also – as parents and ones who are crucially and emotionally involved – started our own scientific board and monitored them ourselves. We set a precedent – no other research board that we know of allows lay people to actually participate, verbally, in the discussions as they ponder their findings.”

Belzberg noted that funding is always a concern because dystonia “is not a well-known disease or a recognizable name, though we fall in the category of MS [multiple sclerosis] and Parkinson’s.”

Asked what advice she would have for a parent of a child with a chronic illness, Belzberg said, “Every family has to deal with their own crises emotionally, spiritually, within their own strengths, and persist in finding answers. Chronic illnesses can be very wearing both for the patient and the family, so it takes a great deal of tolerance and understanding on the part of each to make it through the day.”

For someone who just found out they have a chronic illness, Tannenbaum said, “I would first give them a big hug and sit with them, hold their hands and just listen to them vent – how they feel about the diagnosis, their anger, their fear, their hopelessness, their ‘why me?’

“When they would be ready to hear me, I would tell them that there is a G-d, master of the universe, who loves you more than anyone else loves you in the whole wide world. Everything G-d does is for the good, even though I know it doesn’t feel that way right now. This is a test that G-d knows you can pass; otherwise, He wouldn’t have given it to you…. This is an opportunity for you to grow and to bring out your hidden potential and strengths that you never knew existed within you. Through this test, you can create miracles. Through this test, you can bring good and G-d into the world. Depending on your attitude and perspective, you will be able to help and change other people’s lives. This test is bringing you farther along to fulfilling the potential that only you can do.”