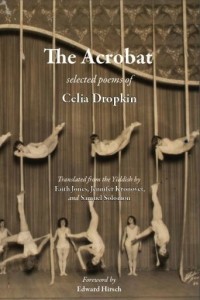

A 1923 studio portrait of the In zikh (Introspectivist) poetry group. Celia Dropkin is surrounded by (clockwise from bottom left): Jacob Stodolsky, Aaron Glanz-Leyeles, B. Alquit, Mikhl Likht, N.B. Minkoff and Jacob Glatstein. (photo from Yiddishkayt)

The Vancouver Jewish Film Festival is welcoming audiences back to the theatre this year. Screenings take place at Fifth Avenue Cinemas March 9-16 and the Rothstein Theatre March 17-19, with some films streaming online March 19-26. Here is but a sampling of the many festival offerings. For the full lineup and tickets, visit vjff.org.

Poetry that burns

As much as the world has progressed in the last century, Celia Dropkin’s unabashedly sexual, emotionally raw, intense, even violent, poems would cause a stir today. Most of her poems are short but powerful, saying things that still would not be said in polite company. A new film, a work-in-progress, offers insight into Dropkin’s life and the circumstances that fueled her creativity, love, anger, imagination.

Burning Off The Page: The Life and Art of Celia Dropkin, an Erotic Yiddish Poet will make its public debut at the Vancouver Jewish Film Festival. Scheduled to be at the screening are local film director and co-producer Eli Gorn and author Faith Jones, who is featured in the film, which includes comments from several writers/scholars and musicians, as well as from some of Dropkin’s relatives. Bracha (Bee) Feldman is the writer and co-producer of the documentary.

Dropkin was born in Belarus in 1887. Her father died when she was little, leaving her mom, a young woman, with two small kids to raise, “mostly resolved to become No One’s wife.… So my mother’s concealed, hot ache / rushed, as from an underground spring / freely in me. And now her holy / latent lust, spurts frankly from me,” writes Dropkin in her poem “My Mother.”

Unconventional views of motherhood were among the many unique aspects of Dropkin’s writings – she had six children herself, one dying in infancy. She was also greatly influenced by a dead-end love affair with Hebrew writer Uri Nissan Gnessin, who she met in her late teens. In 1909, she ended up marrying Samuel (Shmaye) Dropkin, who, because of his political activities, had to flee Russia to the United States a year later; she and their first son joined him in New York in 1912.

In New York, Dropkin was part of the burgeoning Yiddish cultural scene in the 1920s and ’30s. Despite the acclaim she received for her avant-garde work, she never garnered the respect her male counterparts did, and was criticized for depicting women as sexual beings. She struggled with depression, and wrote about it and the dark sides of love. Dropkin died in 1956, having spent the last years of her life painting – a talent for which she also had.

Burning Off the Page is a captivating mix of Dropkin’s poetry, talking heads, music, illustrations, archival photos and videos. (CR)

Life in the “new world”

In iMordecai, Fela (Carol Kane) and Judd Hirsch (Mordecai) are an adorable old couple living the retiree life in south Florida. Their son, Marvin, may or may not be a complete schlemiel (as Mordecai puts it) but each member of the family is dealing with their own stuff.

In a charming opening, Mordecai’s birth in a Polish shtetl is recounted and his memories of the past – including the chasm created in his family by the invasion of Poland and the Holocaust – are cast in striking animation. The family’s real life is also a bit cartoonish – as are the characterizations. Kane, who in this film and elsewhere seems incapable of not being hilarious, is a sweet old bubbe always with a side-eye for any of the other women in town who might be trying to steal her man – after 50 years of apparent devotion. Mordecai is struggling to remember the past while adapting to new technologies – thus the ironic title – and in the process makes friends with a young woman, Nina (played by Azia Dinea Hale), whose own family has its very specific issues.

Although the subjects are sometimes bleak, the film is a breezy dramedy. When Marvin (Sean Astin) explains to his father that Fela is experiencing dementia, the response is subdued brilliance.

“It means that her mind isn’t working like it used to,” says Marvin.

“So, whose is?” the father replies.

There are themes of split personalities, of apples falling not far from trees, and of intriguing coincidences – including running into an old neighbour from Canarsie in the “new world” of Florida. This forces Mordecai to kill off the imaginary brother he invented (it makes sense in the film) for comedic gold.

iMordecai isn’t going to win best picture, but it is a fun and sometimes poignant confection that veers from cheezy to charming to slapstick. When it gets serious, it gets a bit shlocky but damned if the final scene doesn’t get you in the throat. (PJ)

Maintaining a legacy

The stress and anxiety are palpable as Greg Laemmle is forced to consider selling his business, which has been in the family more than 80 years and which is an L.A. institution. But director/producer Raphael Sbarge didn’t start out to make a documentary of this crucial moment in 2019 – and what came after. He was simply interested in the history of the Laemmle family, which goes back to Hollywood’s beginnings.

“Though we had no idea where this film was headed, Only In Theatres took on a life of its own through changing markets and slipping sales,” writes Sbarge on the film’s website. “Then, the pandemic hit and the Laemmle story became the microcosm of the macrocosm – theatres were forced to ask big questions about resilience and viability. The entire Laemmle Theatre chain closed for more than 16 months, and many never reopened. We were able to witness the Laemmles’ extraordinary challenges and triumphs during what was the most tumultuous and emotional 24-month period in the theatre’s history.”

Laemmle Theatres was established in 1938 by brothers Kurt and Max Laemmle, who were nephews of Carl Laemmle, founder of Universal Pictures. The next generations to run the theatres were Max’s son, Robert, and Robert’s son, Greg, who has three sons. The cinemas were apparently groundbreaking in Los Angeles for screening independent and foreign films, and Only In Theatres sets Laemmle’s in the context of the importance of film in general, and arthouse cinemas specifically. He interviews many filmmakers, who talk about the movies that inspired them and the value of seeing a movie in a theatre, of having that collective experience.

Only In Theatres begins with how Greg and his wife Tish met, and gets into the family’s history. Among the interviewees is Greg’s (at the time) 103-year-old great-aunt Alyse, who was married to Kurt and was there when the legacy began.

In July 2019, after a bad year, Greg Laemmle must decide whether to sell that legacy. It is a gut-wrenching choice on many levels and, after months of agonizing over it, considering various purchase offers, he decides he can’t let go. Less than three months later, COVID hits.

Only In Theatres is both a love letter to arthouse cinemas, and an insight into the burden of legacy and how all the accolades in the world don’t pay the bills. If you truly want a business you love to succeed, then show ’em the money. That’s the support that ultimately matters. (CR)

Tradition vs. modernity

Against the magnificent backdrop of the Italian countryside, a family of French Orthodox Jews arrives on an annual two-week sojourn to inspect citrons to be packaged and distributed as etrogs for Sukkot.

Where Life Begins picks up the story of two families – the Italian Catholic farmers and the French Jews – who go back a long way. This year, though, Esther (played by Lou de Laâge), the 26-year-old and still unmarried (!) daughter of the French Zelnik family, is engaged in a profound internal struggle with her faith. She is bridling against the constraints of her religious obligations. At the same time, Elio (Riccardo Scamarcio), one of the sons of the original farm family and now in charge of orchard operations, is questioning the obligations to the land that have befallen him.

The French/Italian, Catholic/Jewish dichotomies are gently juxtaposed but the more powerful contradictions and stressors have to do with separation from family – literal in Elio’s case, figurative but no less wrenching in Esther’s. More immediately, both are confronting their lives in terms of the footprints of the past and the futures they envision for themselves. Each aches for a different path but to embark on it would require a massive break with expectations and everything they have known.

This annual pilgrimage is a tradition made extra festive by the singing and dancing of Georgian migrant farm workers. The joyfulness of the foreigners from the east may not prove that happiness is something one has to travel to find, but it suggests that uprooting from familiar surroundings need not be all grief and loneliness either.

The narrative of Where Life Begins is not an original storyline. Tradition and modernity in conflict; family obligations versus self-actualization; the possibility of forbidden love: these are among the oldest themes in literature and film. Handling these topics with originality and artfulness is what makes or breaks a film like this. This movie does it with nuance and absent simplistic tropes. The southern Italian landscape makes the whole thing easy on the eyes. (PJ)