A bunker in Tirana, Albania, that is now the Bunk’Art art and history museum. (photo by Deborah Rubin Fields)

Albania is a country of great contrasts. It has stunning, clean beaches, so gorgeous that locals refer to them as the Albanian Riviera, and it also has hills and mountains that spring up in all directions. The contrasts seem to extend to Albanians themselves – Enver Hoxha, Albania’s longtime communist dictator, who died in 1985, started off as a partisan fighting the Italians and Germans in the Second World War.

Until not too long ago, Albania existed in isolation. Long before COVID-19 raised its head, Hoxha had kept the country shut off from the world. This is remarkable, given that Hoxha had at various periods aligned his Marxist-Leninist politics with the Soviet Union and China.

As in other communist regimes, many Albanian citizens became suspect during Hoxha’s 40-year reign. They were imprisoned, tortured and murdered. Further, over a 20-year period, Hoxha went on a bunker-building spree. He worried that Albania might be invaded by its neighbouring countries and by the Soviet Union. Between 1971 and 1983, at extreme cost to the general economy, Hoxha had more than 173,000 bunkers constructed. Hundreds of soldiers and civilians died in work accidents. Once the bunkers were built, local citizens as young as 12 years of age were expected to defend them from invaders. The bunkers were only abandoned in 1992, seven years after Hoxha died.

Today, some of the bunkers have other uses. In the capital of Tirana, for example, one series of bunkers has been converted into the Bunk’Art, an art and history museum. In Gjirokastra, there is the Cold War Tunnel Museum.

Hiking is also a fantastic way to see this beautiful country, although, in more remote parts of the country, older Albanians do not speak English and the younger, English-speaking generation is leaving Albania to seek their fortunes in other parts of Europe. Also be aware that even visiting castles requires a bit of hiking over either loose or highly polished stone, so it may be advisable to use walking sticks.

Generally, when people talk about blue eyes, they mean the eye colour of other humans or of their pets. But, in Albania, the Blue Eye is a lovely nature site. Reaching unknown depths (divers have gone down as far as 50 metres without reaching the bottom), the Blue Eye is more accurately a blue hole fed by an underground spring.

Albanian mythology recalls mountain spirits who live near springs and torrents in the northern Albanian Alps. These spirits or zanas are courageous and often protect Albanian warriors, but they can also go the other way, doing evil.

Even some of Albania’s mountains have stories. Take Mt. Tomor, for instance. Baba Tomor, or Father Tomor, is the personification of the mountain, a range whose highest peak is in central Albania. Baba Tomor appears as an older man with a long white beard that reaches his belt. Four eagles serve as his assistants. His bride is the young Earthly Beauty. When his territory is threatened, Tomor battles his enemy, Mt. Shpirag. The furrows running down Shpirag’s mountainside are said to be the knocks Tomor gave to Shpirag. Ultimately, the two fought to their deaths. The young bride is said to have drowned in her tears, which then became the Osum River.

Indeed, this is a country with many local legends. Take the story related to Shkoder’s Rozafa Castle. Apparently, the walls of this ninth-century BCE castle kept collapsing. Only when Rozafa (the wife of one of the three brothers building the castle) was enclosed in the castle walls did it stabilize and remain standing. Booker Prize-winning Albanian writer Ismail Kadare based his book The Three-Arched Bridge on this legend.

One of the spots to visit in Gjirokastra is called Sokaku i te Marreve, or Mad People Street. On this street, there is the reconstructed home of the above-mentioned – but sane – writer Kadare.

More interesting things about Gjirokastra include the Gjirokastra Castle, which houses the remnants of a U.S. Air Force Lockheed T-33. Some claim Albanian forces downed the jet during the Cold War (1957). Others say the plane was an American spy jet forced to land at Tirana’s Rinas Airport in December 1957 after developing mechanical problems and flying off course. Both scenarios are unlikely, but they make for good stories.

In a country that has almost no Jews, it is intriguing to know that (protectively covered by sand) Sarande has mosaics containing images of a shofar, a menorah and an etrog. Apparently, back in the fourth- or fifth-century CE, the Jewish community had its own synagogue in Sarande. According to the late Ehud Netzer and the late Gideon Foerster – the Israeli archeologists who dug there (along with an Albanian team) – this synagogue even had a ritual bath.

In contrast to radical Islam, there is Albania’s Bektashi Order, a Sufi Islamic creed with a long mystic tradition in Albania. The Sufi faith does not force devotees to observe the basics of traditional Islam. For example, the Bektashi creed allows for the drinking of alcohol and does not demand men and women be segregated, nor that women wear a veil. Curiously, this order appreciates Sabbatai Zvi, who was a false messiah, according to most Jews. Baba Mondi, the spiritual leader of the Bektashi sect, calls Sabbatai Zevi a dervish – a Farsi word for a spiritual Muslim who ascetically devotes his life to serving Allah; the term has also been used to describe, in rare instances, a Jew.

Ironically, Berat, the city of 1,001 windows, has a Jewish history museum established by the late Prof. Simon Vrusho, who wasn’t Jewish. Since his passing, the small Solomon Museum has been run by his widow. This museum exemplifies the good relations Albanian Jews had with both the Muslim and Christian community. Amazingly, local non-Jews saved almost 2,000 Jews during the Holocaust.

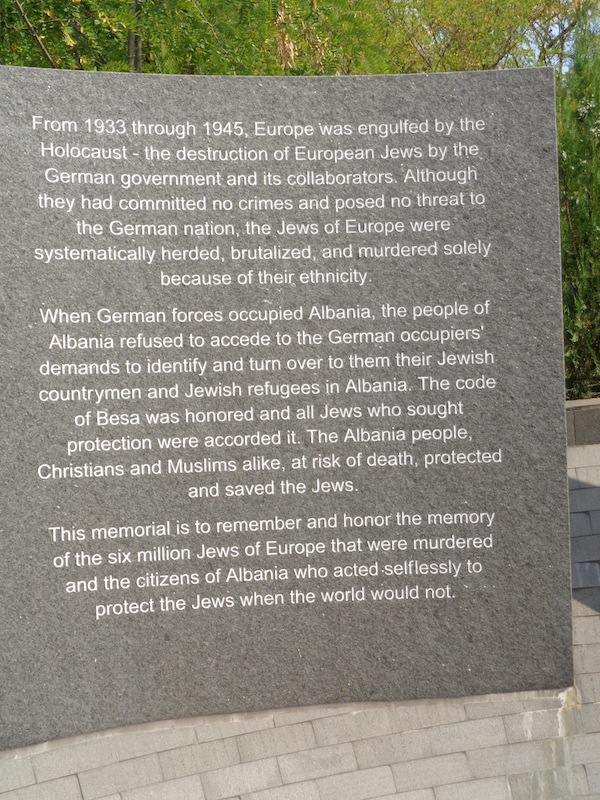

In Tirana’s Grand Park, there is a newly installed Holocaust memorial. It consists of three large plaques in Albanian, English and Hebrew, highlighting the stories of Albanians who saved Jews during the war.

Relatively unknown is an Albanian tragedy that exemplifies the worldwide refugee problem. In 1997, the ship Katër i Radës departed from the Albanian port city of Vlora, carrying 120 refugees fleeing the violence that had engulfed the country following that year’s massive collapse of pyramid schemes. On March 28, 1997, the Italian navy warship Sibilla – acting in accordance with an Italian blockade of Albania (designed to prevent refugees from entering the country) – intercepted, rammed and sunk the Katër i Radës in the strait of Otranto, killing 81 of the refugees aboard. Among the victims were many women and children.

Since ancient times, Jews have lived in Albania. However, there are a few theories about how and when Jews arrived there. According to historian Apostol Kotani, Jews may have first arrived in Albania as early as 70 CE, as captives on Roman ships that washed up on the country’s southern shores. Others report that, in Roman times, Jews already lived in the port of Durres. The Jewish population has fluctuated over the centuries, but most of the Jewish population made aliyah in the 1990s and, today, only a few Jews remain.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.