Bob Bossin as Davy in Davy and the Punk. (photo by Derek Kilbourn)

For legendary Canadian folksinger Bob Bossin, who has called Gabriola Island home since 1991, it all started with “The King.”

“It was Elvis,” he told the Independent about his start in music. Bossin is among the performers featured at this July’s Vancouver Folk Music Festival. “I loved the early rock ’n’ rollers, and asked my parents for a guitar when I was 9. They bought the cheapest one – ‘he’ll never stick with it’ – and I only stuck with it because they said I wouldn’t.

“That would have been 1955,” he said. “It only took a few years for the music industry to take over rock ’n’ roll and turn it mushy. Then, one night in 1958, I was listening to the radio and they played a spare, strange song about a man who was about to be hanged for murdering a woman, a particular woman named Laura Foster. His name was Tom Dooley. It was the damndest song I’d ever heard. I was hooked by folk music and have stayed hooked for 60-plus years.”

For Bossin, “Folk music is just the musical expression of what you might otherwise talk about or write about or argue about or read about.

“I suppose I like performing because I like the attention. I also like that you can get ideas across, sometimes profoundly, once you’ve learned the skills to do that. When I was performing Davy the Punk, my show about my dad’s life in the 1930s gambling business, I loved to show an audience that you could spark their interest and pull them into a world they knew little about, and do it with just a bare stage, a beat-up acoustic guitar and 50-odd years of learning how to tell a story.

“At this late date in my performing career,” he said, “I also realize there is a part of the history of folk music that we old fogies can share, those of us who saw or hung out with Rev. Gary Davis, Jean Carignan, Dave Van Ronk, the Seegers and so on.”

It was in 1971 that Bossin and Marie-Lynn Hammond formed Stringband. Their first album was Canadian Sunset and, with various other band members, they toured for some 15 years and recorded seven albums. They went from one end of the country to other, and back again, more than once.

Writes Bossin on his website, “We played, over the years, in the U.S., U.K., U.S.S.R., Europe, Japan, Mexico and Newfoundland. The list of musicians who sat in or recorded with us is too long to recite, though it includes Nancy Ahern, Daniel Lanois, Stan Rogers, Kieran Overs and Jane Fair. The songs we made (sort of) famous include ‘Dief Will be the Chief Again,’ ‘The Maple Leaf Dog,’ ‘I Don’t Sleep with Strangers Anymore,’ ‘La jeune mariee,’ ‘Tugboats,’ ‘Daddy was a Ballplayer,’ ‘All the Horses Running,’ ‘Lunenburg Concerto’ and ‘Show Us the Length.’”

The music industry has changed in so many ways since he began his career, said Bossin. “When we started Stringband in 1971, there was no indie music scene, virtually no indie recording. Some credit us with starting that whole movement in Canada, and there is some truth to that.

“They say it is harder to earn a living as a musician now, but it is also easier to get your music out there. There are so many more ways to reach specialized audiences like folkies. So, while it probably is harder to be a professional musician, that has never been what folk music is about at its core. I think the internet, the social networks and all that high-tech stuff have been a great boon to folk music, to people making and sharing music about what they and their communities care about.”

Bossin has certainly used technology to inform, educate and influence people on environmental issues. As examples, the video Sulphur Passage was an integral part of the campaign that saved Clayoquot Sound from clear-cut logging, and his 10-minute video laying out the potential consequences of Kinder Morgan’s Burnaby plans has more than 12,000 views since it was posted at the end of April.

“I remember thinking, when I decided to join the fight against turning Vancouver into an oil port, that I probably had one more good fight in me. And it has been a great experience, I’ve met lovely people, been learning a lot,” said Bossin. “On the other side of the ledger, my YouTube video Only One Bear in a Hundred Bites but They Don’t Come in Order, has gone positively viral. It may have even changed a few votes in the provincial election. If it helped get rid of those heartless bastards that have been in power here for far too long, hooray!”

Bossin is quite comfortable mixing music and politics. About the role of art in a society, he said it should be “to make people’s lives better, by the beauty of the sound or the freshness of the vision. Or by contributing to the struggle for a better and more just world. Or, these days, just to there being a habitable world at all.”

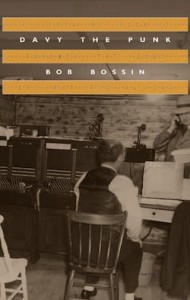

Born and raised in Toronto, Bossin lived in Vancouver from 1980 until he moved to Gabriola. His mother, Marcia, was an artist and his dad was “Davy the Punk” – Bossin wrote both the book Davy the Punk: A Story of Bookies, Toronto the Good, the Mob and My Dad (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2014) and the musical version. His music credits also include the records The Roses on Annie’s Table (2005) and Gabriola V0R1X0 (1994); in the late 1980s, he created the musical play Bossin’s Home Remedy for Nuclear War, which he performed some 200 times. He has written essays, articles and poetry that have been published by various outlets over the years, and his book Settling Clayoquot (1981) was part of the Province of British Columbia’s Sound Heritage Series. In 2007, he published the short story Latkes, which was illustrated by fabric artist and fellow Jewish community member Sima Elizabeth Shefrin – the two met in 2005 and were married in 2012.

When asked by the JI if he’d like to add anything else, he said, “I’m the oldest softball player on Gabriola Island. Possibly ever.”

For more on Bossin, visit bossin.com. For the full Vancouver Folk Music Festival schedule, visit thefestival.bc.ca – the festival starts with a Thursday night concert this year, running July 13-16 at Jericho Beach.