Ida Halpern, right, with Chief Harry and Ida Assu in Cape Mudge, 1979. Chief Assu was the son of Chief Billy Assu. (Image J-00562 courtesy Royal B.C. Museum and Archives)

In 1947, ethnomusicologist Dr. Ida Halpern and hereditary Kwakwaka’wakw chiefs Billy Assu and Mungo Martin, among others, began a decades-long collaboration. They recorded more than 300 sacred and traditional songs that otherwise would have been lost because of the Potlatch Ban and the suppression of Indigenous culture in general. The exhibit Keeping the Song Alive explores these preservation efforts and highlights how these songs are inspiring Indigenous artists today.

Co-developed by the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art and the Jewish Museum and Archives of British Columbia, Keeping the Song Alive is at the Bill Reid Gallery until March 19. The exhibit is co-curated by Michael Schwartz, former director of community engagement with the Jewish Museum, and Bill Reid Gallery’s Cheryl Kaka’solas Wadhams, a practising artist who also is an active member of the local Kwakwaka’wakw Cultural Sharing Group and a participant in the Kwak’wala language program through the First Nations Endangered Language Program at the University of British Columbia.

“I first learned about Ida Halpern at a B.C. Museums conference in Victoria in 2017,” Schwartz told theIndependent. “My colleagues at the B.C. Archives shared the news that they had recently submitted the Ida Halpern Collection to be considered for inclusion in the Canadian UNESCO Memory of the World register. The collection was inscribed in the register in March of the following year but, at that conference, I was inspired by the story of Ida Halpern and thought it would be an excellent topic for an exhibit or project by the JMABC.

“A few months later, I ran into [curator] Beth Carter from the Bill Reid Gallery and we agreed to collaborate on the exhibit. Doing so would expand the possibilities and improve the final project, which definitely turned out to be true. Shortly thereafter, we brought in Cheryl Wadhams, who brought lived experience and essential connections as a member of the Kwakwaka’wakw community.”

A 2020 grant from the B.C. Arts Council made it possible for Schwartz and his colleagues to visit the Kwakwaka’wakw communities in Alert Bay, in Campbell River and on Mudge Island. They did so in early summer of this year.

“The impact is still revealing itself,” said Wadhams of guest curating the exhibit. “In general, it is causing me to think more deeply about my relationship with my community. Our research helped me to reconnect with community leaders back home in Alert Bay. Living in the city, this is so important to me.”

In addition to the historical elements, Keeping the Song Alive includes contemporary art, artist talks, Kwakwaka’wakw dance and drum group performances, and more.

“We were honoured to receive permission from the families to share certain songs,” said Wadhams. “All of the artists in the show are directly speaking to the recordings, the Potlatch Ban, or the contemporary flourishing of Kwakwaka’wakw potlatches. Barb Cranmer is an influential filmmaker whose important films are all based on our culture.

“We first approached Sonny Assu as the great-great-grandson of Chief Billy Assu,” she said. “He has explored the ideas behind these recordings for several years and created a new work for the exhibition. Andy Everson is also sharing a personal family story in his work. Maxine Matilpi supports the community with her beautiful regalia and her deep cultural knowledge.”

Several Kwakwaka’wakw community members and cultural leaders are featured in the exhibition, said Wadhams. “They speak directly to the value of the recordings and their meaning for the community. They are the leaders of today who are teaching our youth for the future.”

“At a time when historic injustices are in the spotlight and racial tensions and hate crimes are high, stories of cross-cultural collaboration can soothe and provide inspiration,” said Schwartz, who described the exhibit as a “capstone” to his time at the Jewish Museum. (He recently became a director of development at Ballet BC.) “The JMABC’s last physical exhibit was in 2015, Fred Schiffer: Lives in Photos. Eight years later, it’s nice to produce another one,” he said.

In an interview with the CBC in 1967, which can be found on the Royal B.C. Museum website, Halpern describes the preservation of these local Indigenous songs as a project close to her heart.

“Some have suggested that Ida’s experience fleeing the Holocaust informed her work, and that this experience may have given the chiefs confidence in trusting her. But it’s difficult to know for certain,” said Schwartz. “It is apparent in her writing that she felt other academics had misrepresented and oversimplified this musical tradition and she sought to remedy this perceived wrong.”

Ida and Georg Halpern fled Vienna shortly after Kristallnacht and, by way of Shanghai, made their way to Vancouver, said Schwartz. “Ida had been a promising pianist as a teenager and intended to pursue a career as a performer, but a spell of rheumatic fever landed her in the hospital for a year, making her practise and training impossible. Her health restored, she studied musicology at the University of Vienna during a time when the field was flourishing and some of the best minds in the discipline were teaching there. It was a transformative time for her.

“Arriving in Vancouver, Ida set out to record and analyze the song traditions of local Indigenous nations,” he said. “She spent close to a decade building trust and often spoke of all the time she spent in kitchens, helping the women prepare food for community events. These efforts paid off when she was invited by Chief Billy Assu to record him singing 100 songs at his home in Cape Mudge.

“Over the course of a week, the two recorded 88 songs, complete with explanations of the history, meaning and significance of each song, when it was to be sung and by whom. This encounter was the initial spark for Ida’s research. Assu was a widely respected leader and his endorsement opened the doors for her to meet with other Indigenous leaders, including Mungo Martin and Tom Willie.

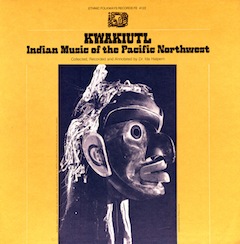

“Selections from these recordings were later published through Smithsonian Folkways Records, through the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, giving them an audience far beyond the academic community. Many of the people we worked with in developing this exhibit spoke to the importance of these records and the fact that they were many people’s first encounter with their own tradition.”

Hereditary Chief K’odi Nelson was one of the people the research group met in Alert Bay, said Schwartz. “He’s an extremely kind and welcoming person, who told us about the classes his mother and aunties started to teach the children the old songs. In the early days, they couldn’t persuade any of the elders to come sing in person, so his mom swiped a copy of one of the Folkways records from the band office. K’odi had a visceral memory of being about 5 years old and hearing the needle drop as he waited behind the curtain to start dancing.”

It is important to note that Halpern and the chiefs’ recordings were made during the Potlatch Ban, Schwartz said. The ban came into effect in 1885 and was in place until 1951.

“By working with Halpern, the chiefs were breaking the law and putting themselves at risk,” he said, “but they saw the necessity to do so. Their children were distancing themselves from their cultural tradition and showing a lack of interest in learning the old ways. Members of the community felt it was safer to assimilate and blend into the dominant society. The chiefs feared that their tradition would die with them; by recording with Halpern, they were essentially crafting a time capsule, making it possible for a future generation to reconnect with the tradition, which we’re seeing happen now and over the past decade.”

Schwartz was quick to point out that the recordings weren’t the only way that the traditions were kept alive during the Potlatch Ban.

“Kwakwaka’wakw leaders violated the ban or navigated tightly around the edges of it in various ways, including by holding gatherings under the guise of Christmas or Thanksgiving dinners,” he explained. “While technically not a potlatch, they were opportunities to undertake the ‘business’ of the potlatch: namings, agreements, honours and so forth.

“These creative solutions in the face of attempted erasure brought to mind for me the story of Hanukkah,” said Schwartz, “How the dreidel was used as a mask for study groups, and the old adage that an idea can’t be killed.”

About the importance of keeping these songs alive, Wadhams said, “Speaking to the singers in the Urban Dance Group, and also back home, I have learned that they find them so valuable. They have them on their phones and listen on YouTube, Spotify, all the time. Living in the city, I started my journey 25 years ago to learn the songs and dances. Having access to these songs really made it possible for me to connect in a new way with my ancestry.”

To watch the Nov. 2 opening celebration of the exhibit and for more information, visit billreidgallery.ca.