Shula Klinger creates her vibrant, whimsical designs with cut paper. The art is then scanned and reproduced as prints and greeting cards. Selections of her work can be purchased at Delish General Store (Granville Island) and Queensdale Market (North Vancouver). To see her full range of work, visit niftyscissors.myshopify.com or find her at the Artisan Fair, hosted by the North Shore Jewish Community at Congregation Har El in West Vancouver on Oct. 16, noon-4 p.m.

Tag: art

Museums adapt using tech

Museloop’s app that it created for Israel Museum. (photo from Museloop via Times of Israel)

How do museums and other purveyors of history attract visitors and make the past relevant, especially as people come to expect more and more digital experiences?

Perhaps surprisingly, Werner W. Pommerehne and Bruno S. Frey recognized the problem more than 36 years ago. In their article “The museum from an economic perspective,” which was published in the International Social Science Journal in 1980, they stated:

“Museum exhibitions are generally poorly presented didactically. The history and nature of the artists’ work is rarely well explained, and little is offered to help the average, uninitiated viewer (i.e., the majority of actual and potential viewers) to understand and differentiate what is being presented, and why it has been singled out. Accompanying information sheets are often written in a language incomprehensible to those who are not already familiar with the subject. There is no clear guidance offered to the collections, and little or no effort is made to relate the exhibits to what the average viewer already knows about the history, political conditions, culture, famous people, etc., of the period in which the work of art was produced.”

Keren Berler, chief executive officer of Israeli start-up Museloop recently put the problem into current perspective. Younger visitors, she noted in an Israeli radio interview this past June, find museum visits passive and boring. She said, especially when seeing museum art exhibits, young people need something more to draw them into what they are seeing. So, her company has designed a museum-based application for iPhone and Android use. The application includes games, such as find-the-difference puzzles, plus information about the artist, all of which will hopefully make the visitor better remember the art and some facts about it.

Interestingly, in describing the games, two of the attributes she mentioned were competitiveness and the ability to take “selfies.” Children as young as 8 or 9 years old can use the app on their own, but younger children would need an adult to assist them.

Right now, the Museloop app focuses on Israel Museum’s under-appreciated (read: under-visited) permanent art collection. This exhibit includes the works of a number of “heavies,” such as Marc Chagall, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin. The goal is to make the experience so appealing that young visitors will then want to visit other museums. Since Israel Museum is paying the start-up for the development and use of the app, visitors benefit by having free use of it.

In contrast, Tower of David Museum has its own in-house digital department. This department has developed its own applications for heightened exhibit viewing.

According to Eynat Sharon, the head of digital media, her department takes into consideration the visitor’s total museum experience. This experience consists of three overlapping circles: the pre-visit, in which a person visits either the museum’s website or mobile site; the actual physical visit; and the post-visit, in which the person digitally shares with friends and family on Facebook, Instagram and other social media what they encountered at the museum. The museum’s technical equipment and apps may be rented by museum visitors for a small fee.

Are these new applications then to be applauded? Some people still need convincing. Last year, art critic Ben Davis reflected on news.artnet.com, “For many, many viewers, interfacing with an artwork through their phone trumped reflecting on its themes. In effect, now every art show is by default a multimedia experience for a great portion of the audience, because interaction via phone is a default part of the way people look at the world.”

Dan Reich, who is the curator and director of education for the St. Louis Holocaust Museum and Learning Centre, said, “Personally, I am not big on technology. You end up with lots of button-pushing but not necessarily a lot of education. As a museum, we are pretty low-tech. We have an audio tour of the permanent exhibit, several stops in the museum where you can press buttons and hear testimony, an interactive map and – more recently – added an interactive screen entitled ‘Change Begins With Me,’ which deals with more recent or contemporary examples of hate crimes and genocide. We have been digitizing our collection of survivors’ testimonies. We have testimonies edited to different lengths. Generally, survivors like to be recorded, knowing their words are being preserved.”

And recent comments on TripAdvisor show that museums don’t necessarily have to be high-tech to succeed in their mission.

Visitors, for example, gave the St. Louis Holocaust Centre high marks.

Other Holocaust learning centres, however, have started taking current technology through uncharted waters. The USC Shoah Foundation now uses holographic oral history. According to Dr. Stephen Smith, the foundation’s executive director: “In the Dimensions in Testimony project, the content must be natural language video conversations rendered in true holographic display, without the 3-D glasses. What makes this so different is the nonlinear nature of the content. We have grown used to hearing life histories as a flow of consciousness in which the interviewee is in control of the narrative and the interviewer guides the interviewee through the stages of his or her story. [Now] with the … methodology, the interviewee is subject to a series of questions gleaned from students, teachers and public who have universal questions that could apply to any witness, or specific questions about the witness’ personal history. They are asked in sets around subject matter, each a slightly different spin on a related topic.” One educator confided that, while the technology is “creepy,” the public apparently likes it.

So, how do museums cope with the possibility that the medium in and of itself becomes the message? In other words, how do museums keep their audiences from being distracted by the technology? At the same time, how can museums survive financially if they follow goals that differ substantially from those of visitors, funders and other supporters?

A few months ago, Canadian entrepreneur Evan Carmichael offered guidelines at an Online Computer Library Centre conference. His suggestions seem applicable to museum administrators as well: express yourself, answer their questions, offer guidance, involve the crowd, “use your audience to create something amazing … create an emotional connection, get personal, and hold trending conversations, go to where things are happening, be there.

Time will tell whether the advent of museum-related high-tech will realize Don McLean’s 1971 tribute to Vincent Van Gogh’s art: “They would not listen, they did not know how. Perhaps they’ll listen now.”

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.

Overlapping exhibits

“Girl with Flower” by Esther Warkov, 1964, acrylic on canvas. (WAG collection; gift of Arthur B.C. Drache, QC, G-98-296; photo by Leif Norman)

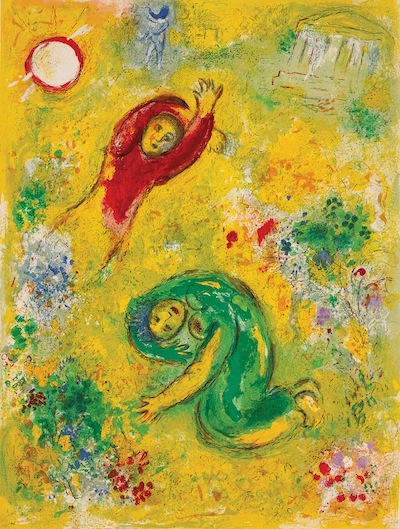

Russian-born Jewish artist Marc Chagall (1887-1985) was a modernism pioneer. So much so that Pablo Picasso proclaimed that, when Henri Matisse dies, “Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what color really is.”

In the early 1920s, Chagall left Russia for Paris. In 1941, he escaped France and reached safe haven in New York. He returned to France a few years after the end of the Second World War.

“This sense of displacement Chagall feels throughout his life is reflected in his works, often featuring characters who hover over the earth…. Even if they’re lying down, they’re sort of levitating,” said Andrew Kear, Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG) historical Canadian art curator. “There’s a sense of rootlessness to his work that’s quite interesting, and it’s reflected in his later work, too. By the 1940s – an important time for Chagall – he loses his first wife, his first love really, Bella, to cancer in or around 1944 … and is absolutely distraught.”

In an exhibition overseen by Kear, WAG has brought in the exhibit Chagall: Daphnis & Chloé from the National Gallery of Canada (NGC). It will be in Winnipeg until Sept. 11.

The exhibit, the latest NGC-WAG collaboration, features 42 lithographs, widely considered the crowning achievement of the artist’s career as a printmaker. The series depicts the semi-erotic tale written by the ancient Greek poet, Longus. Through fanciful compositions and bright hues, Chagall expresses the pastoral idylls of the young goatherd Daphnis and the young shepherdess Chloé on the island of Lesbos.

At WAG, there is also a complementary mini-exhibit called Chagall & Winnipeg, which tells the little-known tale of friendship between Chagall and former WAG director Dr. Ferdinand Eckhardt through letters, photographs and works of art.

“In addition to sketching out the story, this second exhibition … include[s] a number of paintings by Chagall that we’ve borrowed from the NGC and the Minneapolis Institute of Art,” said Kear.

In addition to these two Chagall exhibits, WAG is featuring Winnipeg Jewish artist Esther Warkov in an exhibit that includes her work from the 1960s to the 1980s. It runs until Oct. 16.

Born in 1941, Warkov did not do that well in school, but there was a lot of family pressure to succeed. By chance, she discovered jewelry making as a young teen, which, in turn, exposed her to the world of fine art. She eventually studied art at the University of Manitoba.

Today, Warkov is one of Manitoba’s most distinguished artists. This current exhibit highlights a celebrated and defining period of her work, which was forged in Winnipeg’s North End. Her stylized motifs reveal the clear influence of the eastern European immigrant community’s Jewish folk art roots.

“Although abstract painting was the most common form of contemporary art in the 1960s and 1970s, Esther really bucked the trend,” said Kear. “She was very interested in the human figure, representational drawing/painting, and in paintings that tried to convey a story. It’s this kind of point where she really outlines nicely with Chagall. Chagall’s paintings are very much recalling memories and tell[ing] a story.”

Warkov’s work during this featured period was large-scale and multi-paneled. “It’s not just a painting on one canvas,” said Kear. “It’s multiple canvases that are sort of cobbled together, in a way, to make almost loose grids. Her work is narrative, seems to tell a kind of story, but you’re not sure what the story is. It’s very whimsical and draws a lot on memory.

“I had the pleasure of meeting her for the first time a couple weeks ago,” he added. “I was curious about how she paints, or went about making these works. Apparently, she very rarely started with a coherent plan. She would start with one canvas and do an image on it. That would lead into another image that she’d tack on this other canvas next to the original one, to build the … visual story. But, it was a story she was making up as she went along. I thought she would plan it out first, but that’s not how it went down apparently.

“She’s got a wild sense of humor and great wit, which are really reflected in the titles of her works, [which] are often very long.”

WAG director and chief executive officer Stephen Morris said, “When we installed the exhibition a few weeks ago and we had the works up – many of them painted 40 to 50 years ago – they were as fresh, relevant and dynamic, I think, as the day they were painted. They reference so many interesting stylistic developments, but I’d also say they reach into the heart of who Esther is – someone who has lived in the North End for years, exposed to not just the Jewish culture, but also to Jewish folk art and eastern European traditions … that whole interesting development in terms of painting which you see in her work.

“Esther also brings people into interesting scenarios with her paintings and, in the composition, it can be a little unnerving, a little jarring. But, there is, with both her and with Chagall, a surreal aspect. So, while they’re painting recognizable images and motifs, the way they’re composed takes us back a bit and actually twists things. Some call it ‘the dream,’ others something else. Regardless, it’s delightful and one could see an overlap between the artists in terms of imagery.”

Morris enjoys being able to “bring cultures and ethnicities together.” He said having a famous Russian artist like Chagall next to Warkov, “who, in a way, had a much more regional impact, I think it’s interesting. I love the fact that a visitor can walk between Chagall and Warkov and, yes, they know they’re in a different space, in a different time, with a different artist, but they’ll also see connections.”

Of those connections, Morris pointed to how Warkov’s “roots overlap with Chagall’s roots, in terms of her life, faith and culture.”

The Chagall exhibit is set up in a series of small spaces to highlight the story of Daphnis and Chloé – visitors walk through it in a chronological way. Warkov’s work is displayed in one large gallery and visitors are surrounded by her canvases.

Also at WAG this summer are several permanent galleries, as well as a major retrospective of Winnipeg artist Karel Funk, who, Morris said, “is at the height of his career.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.

Honorary degree for Frimer

Linda Frimer was honored earlier this month by the University of the Fraser Valley for her artistic, humanitarian and philanthropic contributions and accomplishments. (photo from UFV)

For Linda Frimer, art is a form of reconciliation, and creativity a means of expressing the love within us all. The Vancouver artist has been sharing her art to heal, help worthy causes, and reconcile nature and culture for more than 35 years. In recognition of her artistic, humanitarian and philanthropic contributions and accomplishments, Frimer received an honorary doctor of letters degree from the University of the Fraser Valley at its June 2 afternoon convocation ceremony at the Abbotsford Centre.

Born in Wells, B.C., and raised in Prince George, Frimer connected with nature early on, and it informed her artistic development from the start. “I always had a pencil in hand and was allowed to roam the forest freely as a young girl,” she recalled.

Born a few years after the Second World War ended, she heard the adults in her family whispering about the devastation of the Holocaust. Even decades before the war, her family faced hatred and expulsion. Her grandfather fled Romania during the pogroms in the late 19th century, becoming one of the “footwalkers” roaming Europe, then following the Grand Trunk Railroad in Canada to its terminus in Prince George, where he became a merchant.

“I was too young to understand it all, but I knew something very bad had happened,” said Frimer. “I was a highly sensitive child, and absorbed the pain and anguish that others were carrying. I turned to nature for healing and reconciliation. I would enter the forest with a sense of awe and wonder. It’s what unites all people. When we suddenly see a magical tree or a sunset that leaves us breathless, that wonder belongs to everyone. I’ve always wanted to bring together the worlds of nature and culture. They are all connected, and recognizing that interconnectedness facilitates healing.”

Compelled by a desire to reflect the pain of her community and work towards healing, she created many works of art examining this theme. She co-founded the Gesher (Hebrew for Bridge) Project, a multidisciplinary group that helped Holocaust survivors and their children express their traumatic experiences through art, words and therapy.

Reflecting on the project during a talk she gave to the Canadian Counseling and Psychotherapy Association, she noted that creative expression is a critical component to healing. “I’ve done work that reflects my culture and my people and their plight, but I don’t want to get caught in the dark places. I want to share reverence between all cultures. I want to bring light and love to the forefront.”

From an early age, Frimer felt an affinity for the aboriginal people she grew up near in rural British Columbia. Her connection became more formalized when she befriended Cree artist George Littlechild (also a UFV honorary degree recipient). The two felt an immediate connection through their interest in incorporating family and history into their art and their use of vibrant colors. They have collaborated to produce art shows presented in venues such as the Canadian consulate in Los Angeles, and produced a book titled In Honor of Our Grandmothers.

“Both of our peoples have been through so much that we felt a real connection,” explained Frimer. “Growing up, I felt a real sense of ‘otherness’ and not fitting in. Many aboriginal people can relate to that, too.”

Frimer’s affinity to nature has led to her supporting many environmental causes. Her paintings for the Wilderness Committee, the Trans-Canada Trail, the Raincoast Environmental Foundation and other groups have raised funds for wilderness preservation, and also raised awareness of threatened forests and ecosystems.

“I love my environmental work because I know that’s where I can make a difference,” she said. “I am committed to helping to preserve endangered species and ecosystems, as well as helping people at risk or in crisis.”

Frimer spent her 20s raising her children and developing her artistic skills by finding mentors with whom to study. She didn’t begin her formal training until she was 33, when her last child started school. She then finished a four-year degree at Emily Carr in three years, receiving credit for her prior learning and artistic work.

More than three decades into her career, Frimer’s paintings and murals can be found in galleries, synagogues, churches, retirement centres, hospitals, hospices, schools, transition houses, corporate offices, and public and private collections. She has been very prolific but says it’s been easy to create so much art because she feels she is merely a vessel for a strong creative force. “It’s like joy coming through me, rather than me making it happen,” she said.

Frimer has received many accolades, honors and titles, but said her favorite title is “Grandma.” She and her husband Michael raised their blended family of eight children and now enjoy the company of nine grandchildren. “It’s profoundly important, especially for the Jewish people, who have lost so much, to rebuild the family we’ve lost and share reverence with others who have had similar losses,” she said.

Still, receiving an honorary doctorate is a special distinction for her. “My parents would have been extremely proud, and I know that my husband and children will be too,” she said before the convocation. “You can’t really declare yourself a successful artist – you need affirmation from the outside. I’m so grateful that my messages have been heard, and that the care that I’ve put into bringing more culture, nature, creativity, expression, healing and light into the world through the gift of art is being honored.”

For more about Frimer and her art, visit lindafrimer.ca.

This week’s cartoon … March 11/16

For more cartoons, visit thedailysnooze.com.

Kids can find own art path

Shula Klinger (photo by Shahar Ben Halevi)

When artist and mother Shula Klinger was searching for ways to inspire her own two boys, she learned how important it is to let a child find their own creative path. She has translated this lesson – and her artistic expertise – into a new in-home class for young children.

“I provide the space and the stimulations but I let each child discover what triggers him to create art,” said the illustrator and writer. “I follow a simple principle that art is everywhere, we don’t have to use our mind to find it, we don’t have to work our brain to call inspiration, we just need to open up our eyes and let our senses lead us.

“We are all different but we still use the same methods to express ourselves,” she continued. “I invite the child into my house, into my very own working space, where he can find his very own creative space. I let the child lead the process, I don’t follow common doctrines of art educators who show children a painting and ask them to paint the same way. I teach them to think about the process and not about the product.”

Klinger moved to Vancouver from England in 1997 to do her PhD in education at the University of British Columbia. She met her husband Graham Harrington in Kitsilano and the couple moved to North Vancouver, where they are raising their two young boys, Benjamin, 8, and Joel, 4.

Klinger has published a young adult’s novel, The Kingdom of Strange (2008) and illustrated a graphic novel, Best Friends Forever: A World War II Scrapbook (2010), with author Beverly Patt. At the moment, her focus is on the in-home classes, as well as the launch of a video series called Art is Everywhere, co-created and co-hosted with Andrea Benton of Raising Boys TV.

“We want to provide an alternative to the art children have been learning in commercial art schools,” said Klinger. “We want to let them explore, search, discover, play, experiment and learn – mostly learn the how and why of creating their very own art. This is why we are all here. Ever since the caveman left his handprint on the walls of his habitat, we are all looking for ways to leave our mark, sound our voice, tell our story. We just need the freedom to find our own path. That’s what I try to teach.”

For more information about Klinger, visit shulaklinger.com. The video series can be purchased at raisingboys.tv/artiseverywhere.

Shahar Ben Halevi is a writer and filmmaker living in Vancouver.

Using art to bridge peoples

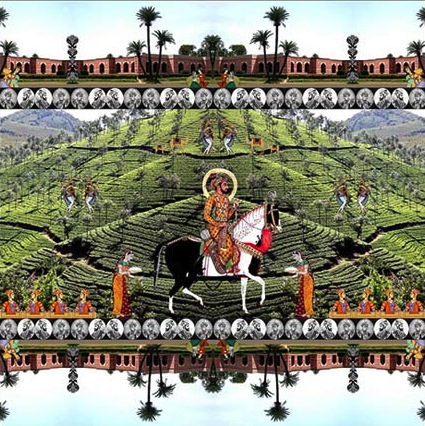

The gallery includes work by Almagul Menlibayeva of Kazakhstan. (photo from AMOCAH)

When people in Israel saw that Belu-Simion Fainaru and his partner Avital Bar-Shay were considering opening yet another art museum/gallery, some eyebrows were raised. But what this dynamic duo in life and in art had in mind was much more than another one-dimensional art space. Their far-reaching ideas will likely quiet the doubts of any naysayers.

Fainaru and Bar-Shay, both Jewish artists living in Haifa, decided to create an art meeting space for Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Bedouin and Druze artists – a place where they could display their art alongside one another. They created the Arab Museum of Contemporary Art and Heritage (AMOCAH) in Sakhnin in the Lower Galilee, which was declared a city in 1995 and has a population of 25,000 of mostly Muslims and a minority of Christians. It also is home to a significant population of Sufis, Muslims who adhere to a mystical stream of Islam.

Bar-Shay and Fainaru originally met in Israel. Fainaru made aliyah from Romania in 1973. A successful visual artist, he has curated exhibits around the world, making international connections along the way. Bar-Shay is an Israeli-born artist, designer and architect. She has exhibited in Israel and abroad and has vast experience in public art, working as a cultural entrepreneur. She specializes in artistic activity in the periphery.

The idea for AMOCAH started with Fainaru and Bar-Shay initiating and curating the Haifa Mediterranean Biennale four years ago. This led to a second biennale in 2013, which took place in Sakhnin. At the Haifa biennale, they used shipping containers to exhibit the artwork. In Sakhnin, the biennale was held in a building that the town’s mayor offered for the occasion.

“Right now in Israel, a lot of … Jewish people feel a special energy when it comes to Sakhnin,” said Fainaru. “So, we did this big project in the Sakhnin area, where a lot of Jewish people are already using various art mediums to bring communities together.”

Fainaru said that the various communities do not usually do things together and, even within the Arab community, Muslims and Christians generally keep to themselves.

“The art will have an urban dimension and we can approach art for a population that’s not very familiar with contemporary art,” said Fainaru. “We think it’s important to decentralize the art scene in Israel.”

Going with the biennale (Italian for every two years) concept seemed the most feasible, with politics and budgets in Israel regularly being in flux. “We had a big project with the Ministry of Education, but a few months after we decided to move ahead with [the minister], he [had] just resigned,” noted Fainaru, as an example.

While the idea of a biennale was born 100 years ago in Venice, Fainaru and Bar-Shay wanted to go with that premise and added a new twist – creating a biennale melting pot of cultures, and eventually transform that into a permanent museum in Sakhnin.

“We think countries around Israel and the Mediterranean should cooperate and exchange ideas in the area of contemporary art,” said Fainaru. “We put a lot of emphasis on education and doing workshops with artists from abroad.

“We want to develop projects under the umbrella of the biennale and museum, also with Jewish and Arab children – the next generation – to communicate and get to know each other, have fewer misconceptions, and make a better living here not based on violence.”

It took some time and meetings with the right people to get the Sakhnin museum off the ground. Fainaru and Bar-Shay met with the mayor of Sakhnin, Mazin G’Nayem, who was open to the idea. The mayor spoke with his culture deputy and the pieces began to fall into place.

“He [the mayor] thinks it’s important to have contact between Jews and Arabs, as we have to live together,” said Fainaru. “He understands that art will help the people of Sakhnin and promote coexistence between Jews and Arabs. He saw that with the football team he put together that has Jews and Arabs playing together.”

During the first biennale in Sakhnin in 2013, Sakhnin was flooded with people coming to participate in the festivities. AMOCAH is open to the public and, so far, the majority of the visitors have been students of contemporary art. The educational component of the museum is still being developed. “We hope, with these educational activities with the biennale, Israel’s sense of art will become known to people all around,” Fainaru said.

AMOCAH carries art from the various cultures in the region and from different religions, but Fainaru is especially proud of the art coming from countries without political ties to Israel, like Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Turkey.

“Normally, relations between Israel and Turkey are very bad,” he said. “Even I was dismissed from a biennale exhibition in Turkey, because of war between Israel and Gaza [last] summer.”

To facilitate cooperation between the Jews and Arab artists involved, the biennale and the museum are being organized by both communities.

“Tel Aviv-area people are self-sufficient in art, culture, cinema, food … in life,” said Fainaru. “They don’t feel they have to go to another place inside Israel. But, in the periphery, what we’re doing is creating an alternative activity in art in Israel and having an influence on life here – making a change and bringing art to people while incorporating cooperation between Jews and Arabs and neighbors around. This is just a beginning.”

The next Sakhnin biennale is scheduled for the end of 2015, with Fainaru and Bar-Shay already working to bring in the works of many new artists from Israel and abroad.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.

This week’s cartoon … Feb. 13/15

For more cartoons, visit thedailysnooze.com.

Lifelong art student

Toby Nadler (photo from Louis Brier Jewish Aged Foundation)

On Thursday, Oct. 23, Louis Brier Home and Hospital hosted an exhibit of accomplished artist and resident Toby Nadler’s work. The exhibit was open to all residents.

In 1970, Nadler began to study oil painting at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art with the late Arthur Lismer, one of Canada’s Group of Seven. After completing a teacher’s certificate at Macdonald College in Montreal, she spent four years teaching children at elementary schools in Montreal’s inner city, where art was one of the subjects, and took evening art courses at Concordia University. She graduated from Concordia in 1980 with a bachelor of fine arts degree, majoring in studio art.

Later, she studied watercolor and multimedia art with Judy Garfin, a Vancouver artist, at McGill University. After a few years, Nadler became interested in Chinese watercolors and calligraphy, and studied privately with a group of other Westerners. The teacher was Virginia Chang, who exhibited her students’ work.

In 1984, Nadler and her late husband Moe moved to Vancouver. Nadler wished to continue studying Chinese art in her new city. She also studied Mandarin at the Chinese library and watercolors with Nigel Szeto at the Chinese Cultural Centre. He was impressed with her work but, after seeing her Western paintings, recommended she continue with her own style, as her personality did not come across in the Chinese paintings to the same degree.

Nadler joined the English Bay Arts Club and the University Women’s Club, where she studied watercolor with various artists, as well as exhibiting there. After a few years, she became an active member of the Federation of Canadian Artists. She volunteered and took courses with their artists and exhibited her own work around the city, including at the Vancouver Public Library. During an exhibit at Oakridge Shopping Centre, an art dealer from Hong Kong admired her work and wanted to know if she had unframed paintings, so that he could roll them up and ship them to his two galleries in Hong Kong. He bought 10 works.

Studying with Lone Tratt, Nadler took watercolor and acrylic courses at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver, where she also exhibited. Upon request, she donated six of her paintings to decorate their seniors lounge. Her home was decorated with many of her paintings.

A resident of Louis Brier since August 2014, Nadler still occasionally paints at her leisure. The Louis Brier Jewish Aged Foundation accepted her donation of more than 10 paintings as part of their collection to decorate the halls of the home. They also have another few pieces, which they will use to decorate the interior of residents’ and staff rooms. It is hoped that her unique style will bring pleasure to all who see them.

At the Oct. 23 exhibit, Nadler’s son, Peter Nadler, spoke, giving a history of his mother as an artist, and Dvori Balshine thanked Nadler for all of her artwork donations. Music therapist Megan Goudreau and recreational therapist Ginger Lerner composed and performed an original song in Nadler’s honor about her contributions to the art world.