Anne, left, and Eva Gitelman. (photo from Deborah Rubin Fields)

The things we take for granted. Today, we spend countless internet hours looking for someone (or something). We assume increasingly rapid communication systems will effectively power these searches. Yet, for Eva Poll and Anne Rosenthal Schiffman, my paternal grandmother’s nieces (my first cousins once removed), staying in touch was a tremendous undertaking.

Beginning in the mid-1920s and continuing for almost 70 years, these two sisters struggled to keep in contact with their three Pinsk siblings, once their orphanage had shipped them and 32 other Jewish orphans to adoptive Jewish families in the United Kingdom.

How did I piece together this faraway story of my Pinsk relatives? The truth is that until their death, my cousins Eva and Anne held on to letters, cards, diaries and photos from Pinsk (today a city in Belarus). Through these saved items, my family’s story emerges.

Eva was born in 1913 as Chaya. She was the fourth of five children born to Avrom and Shaina Basya Gitelman of Pinsk. Anne was born in 1916. She was named Chana. Their older siblings were Hershel, born 1906, Sarah Leah, born 1907, and Devorah, born 1909.

Prior to 1918, I know little about Eva and Anne’s life. But late that summer, both their parents died within weeks of each other. With their deaths so close together, the parents might have succumbed to either the influenza pandemic or to starvation (giving their five young children whatever food they had been able to scrounge). According to Azriel Shohet, author of The Jews of Pinsk, 1881-1941 (translated from the Hebrew by Faigie Tropper and Moshe Rosman, edited by Mark Jay Mirsky and Moshe Rosman), at the time, conditions in Pinsk were terrible.

Eva and Anne went to live in the Jewish orphanage at 2 Dominikanska St. It is not known how my older (but still quite young) cousins managed, either on their own or with assistance.

My paternal grandparents had just emigrated to Chicago but, somehow, they learned the children had been orphaned. My grandfather contacted the Joint Distribution Committee, asking for photos of the orphans. With eight of their own children, it is unlikely my grandparents were in a position to provide much assistance.

All I know is that by age 16 or 17, Sara Leah married Yisrael Kuper and that they quickly began their own family. Devorah began working in the Pinsk veneer factory and lived with the Kupers. At some point, Hershel married a woman named Faigel and became a father.

What I have learned through research is that the orphanage’s economic situation worsened in the early 1920s. Shohet writes that even though the staff took good care of the orphans, it sometimes had to feed the children hot bean cereal instead of bread. In August 1923, the orphanage sent the following “advertisement” [translated from Yiddish] to the Pinsker Relief Fund in London:

Chaya learns in the school and Chana Gitelman learnt dressmaking. In peacetime, they lived in a village near Pinsk. In the war, they became ruined. The parents died and the children were taken to an orphanage…. They … are good children and very diligent. (Courtesy of David Solly Sandler, author of The Life and Times of the Children from the Three Pinsk Jewish Orphanages in the 1920s)

By 1924, the two sisters and their orphaned friends knew they were candidates for adoption by Jewish families in Britain. In 1924, close to the time of Rosh Hashanah, a friend named Faigel Bambel wrote the following in Anne’s autograph book:

To remember

To Chana Gitelman

When you go away to a faraway land, don’t forget me…. Don’t forget how it was for you here where we were together. Today I send you my wishes, and I believe that we’ll remain good friends. (Yiddish translation by Amy Simon)

By 1926, the orphanage had found homes for Eva, Anne and 32 other orphans. A few months before departing Pinsk for the United Kingdom, the siblings had their last family photo taken. (For unknown reasons, Hershel and family are not in the picture.) At sailing, Eva was 13 years old and Anne was 10 years old. The sisters never saw Pinsk again.

While I never asked Eva or Anne about the psychological toll of leaving family, the onboard ship photo seems to indicate the difficulty of parting. Eva is the only child holding a suitcase. According to her nephew, Colin Schiffman, Eva saved all her Pinsk correspondences in this suitcase. Moreover, Eva kept the suitcase under her bed, taking it out to use as a writing table.

They were adopted by two different Jewish London families: Eva by the Polsky family (Eva later shortened her family name first to Pole, then to Poll) and Anne by the Rosenthal family. To their credit, these two families permitted the girls to maintain contact with one another, as seen in the lovely 1929 photo from their adolescence.

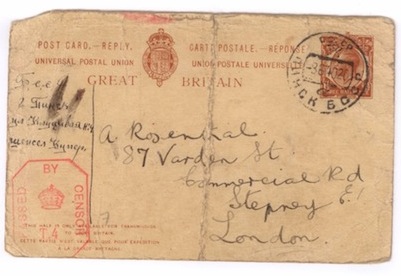

From saved correspondences, I discovered that until at least 1939, the sisters were in contact with the Pinsk part of the family. To insure responses to their letters, Eva and Anne purchased two-part (send-and-receive) international postal cards. One saved card already shows the Second World War censor stamp the British employed after declaring war on Germany.

Anne must have told the Pinsk family about her plans to marry Bobby Schiffman on July 14, 1940, as brother Hershel sent a message: “Chana, how are you, what’s new with your wedding and with work? Regards to your parents and to your husband/groom.” Cousin Chaya wrote: “Regards to Chana and her husband.” Bobby and Anne had three sons: Alan, Stephen and Colin and eventually several grandchildren.

Eva chose to remain single. She had been engaged at least once, but did not go ahead with marriage because she had promised her Pinsk family she would always look after her little sister. Eva’s nephew Colin confirms that, by 1941, Eva was already living with the Schiffmans in London. Colin recalls that, as a young woman, Eva led a busy social life. For most of Eva’s working life she was the final quality-control person at the clothing factories at which she worked (and she sent back many items!).

After the Second World War and for the next 50 years, Eva searched for family, but kept her feelings to herself. As such, she never revealed how much emotional or physical energy it demanded to send numerous handwritten letters to Jewish newspapers, to the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, to the JDC, to Yad Vashem. Just as important, she never divulged how hard it was waiting for replies. While she found relatives in such far-flung places as the United States and Argentina, she unfortunately discovered no Pinsk family member had survived the Nazi onslaught.

With Yiddish-speaking relatives, the sisters communicated in (both written and spoken) Yiddish, but together they conversed in English. As the years went by, the two sisters seemed to enjoy a quiet life of working in the family’s Newbury Park house and garden, taking care of Colin, Bobby and the family cat, and, importantly, keeping each other company.

Anne died in August 1995. Eva died in April 2001. Despite trying childhoods, a difficult passage from one country to another and an upbringing in two different homes, until the end, the two sisters remained tremendously devoted to each other.

In the macro, their cherished papers provide an eye-opening glimpse of one corner of early 20th-century Eastern European Jewry. In the micro, they open a fascinating window to the lives lived by some of my relatives, lives marked by separation, on the one hand, and continuity, on the other.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.