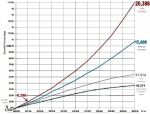

The four lines in this diagram are projections based on four levels of fertility of the general population. In 2059, there could be more than 20 million people in the state of Israel. However, if the birthrate drops to the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman during her lifetime, in 2059, it would be only about 10 million. (image from population.org.il)

While by no means unique to Israel, with less space than most to work with, it is happening a little faster there – population overload. While some feel it is too late to do anything to alleviate the problem, one growing group of Israelis is putting its energy into making a bid to re-educate the public about the need for stabilization, as opposed to growth.

One of the leaders in the group is Prof. Alon Tal, chair of the department of public policy at Tel Aviv University (TAU). Tal was born and raised in North Carolina before making aliyah after high school, at the age of 20.

“I’m an activist trapped in the body of an academic,” he quipped. “For many years, I fought it, but I tried very hard to stay an advocate for environmental interests in the country.”

A father to three daughters, Tal decided to move to Israel, as it seemed like a unique and exciting place, and he wanted to take his Jewish identity seriously.

“In Israel, every year, we take open spaces and turn them into houses, highways and commercial centres,” he told the Jewish Independent. “We live in a small country. We have the responsibility to give quality of life, to find a better way. We’re not meeting our responsibility to our great land.”

Tal is at the forefront of Israeli leaders calling on the Israeli government to adopt a policy that stabilizes the population.

“We have to cancel financial payments to families with more than two children,” he said. “We should not be encouraging it [larger families]. It means that we need to strengthen the status of women in the communities, like in the Orthodox communities. We need to make contraception available free of charge, [grant] basic rights of women to abortion, by removing some of the strings attached…. We need a policy that [aims for] stability, rather than maximum growth.”

While most Israeli Jews are raised with the fear that the Arab population will outgrow the Jewish one, Tal is trying to make people aware that there are lower fertility levels being seen in most populations, including Arab ones, while Jewish are on the rise.

A main thrust to all this need for change, Tal said, is the alarming rate of vanishing nature.

“To me, it’s very clear,” he said. “Israel’s wildlife is disappearing. It’s happening faster than I thought it would. If we had 10,000 gazelles 15 years ago, there are only about 2,500 now and they were just declared endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Pretty much, when you go through that report, you can see everything is on the decline. One-third of mammalian species are described as endangered or extinct. It’s a horrible thing that Israel is letting this happen. I don’t want anyone to [be able to say] they didn’t know this was going on.”

When the Independent contacted Tal to be interviewed for this article, he was en route to the official opening of a new museum at TAU – Israel’s Museum of Natural History.

Tal has helped write new laws and has also been involved, indirectly, with Israel’s National Nature Assessment Program (NNAP). Recently, the first State of Nature report came out, explaining how construction and agricultural development have introduced some invasive species to Israel – to the extent that several bird species in southern Israel can no longer survive.

NNAP has established a program that operates out of the new museum, as part of a joint initiative with Jewish National Fund Israel, the Environmental Protection Ministry, and Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Its mission is to promote proper land management based on the science of open areas with Israel’s biological diversity in mind.

“It’s not a policy thing,” said Tal. “We want to save wildlife, set aside land, create ecological corridors, stop hunting and stabilize population growth.”

Although Tal acknowledged that the need to do these things is not news to many people, he is adamant that it must continuously be communicated in different ways to get to the tipping point of producing change.

“I was on television three times this week,” he said. “Every time I’m there, I mention what’s going on. I’m doing what I can do. Everyone needs to make a contribution.

“This is really about a change in Israel’s cultural DNA. We were raised on maximum population growth. We now have to stabilize. We have to tell people that, if we want to be responsible for other species that means we have to stop the incredible hemorrhaging of open spaces. If we don’t, then there won’t be any more nature.”

Tal plans to keep meeting with every willing influential person in order to educate enough people to swing the pendulum towards restoring nature. He anticipates that the new museum will be helpful in this regard.

“In order to change something, you have to know,” said Tal. “You have to look at the habitats, species logs, and take measures there. Anybody who considers Israel a promised land or has an emotional attachment to this holy place – Christian, Muslim, Jewish – we all share this responsibility. Just like how I make contributions for the Amazon rainforest, because I understand how it affects me. If you have an initiative you feel connected to, you should support it. Come to Israel and get involved, go on vacation and get involved, write letters to Israel’s decision-makers letting them know you expect the Jewish state to be a responsible trustee of its nature.”

For more information, visit population.org.il.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.