Harpo Marx and the Bodnes in the Rose Room. The hotel’s list of illustrious guests is almost literally endless. (photo from Algonquin Kid)

Michael Elihu Colby had the unique privilege to be brought up in New York’s legendary Algonquin Hotel. Well, not exactly brought up in it, but his grandparents owned it from 1946 to 1987 and he was there a lot.

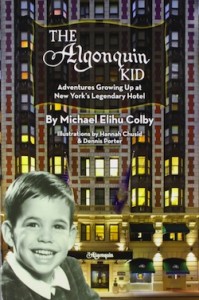

Colby’s book, The Algonquin Kid (BearManor Media) is chock-a-block with stories from his experience as a youngster hanging around and also tales handed down through the years.

Grandma Mary and Grandpa Ben Bodne loom large in the book, as they did in the hotel and, by extension, cultural life in New York City in the 20th century. The grandparents were from the southern United States and Ben became wealthy through oil during the Second World War and afterward sought to parlay his money into something else. Despite having no hotel experience, the couple threw themselves into the adventure.

The hotel was a dilapidated shadow of its former glory. On top of the million dollars the hotel cost, the family had to sink another $300,000 into making it decent. This renovation was not welcomed by all the guests. The hotel had residents who had lived there for 20 years and who were highly averse to change.

The book is fabulously gossipy and it would have been shorter, maybe, if Colby had listed the celebrities he didn’t run into. Tennessee Williams, Norman Mailer, William Saroyan and John Cheever were among the literary lights.

Although this was well past the hey-day of the famed Algonquin Round Table, some of those names were still hanging on, too.

Show biz figures included Ingrid Bergman, Kitty Carlyle, Tallulah Bankhead and Angela Lansbury, the latter two of whom lived at the hotel. Rosemary Clooney, Irving Berlin, Noel Coward, Ella Fitzgerald … the list is almost literally endless.

The Algonquin was welcoming to actors and artists blacklisted during the McCarthy era and also to African-Americans at a time when this was unusual. Among the bold-faced names in this category: Maya Angelou, Coretta King, Thurgood Marshall and Oscar Peterson.

The hotel staff included its own characters, like a telephone operator who had the skills of the CIA at tracking down anyone anywhere, and a quick-thinking maître D’: “When a guest found a fly in her salad, he popped it in his mouth, swallowed down the evidence, and exclaimed ‘Delicious! A raisin.’”

This is a book of family stories and such stories, especially when the family is filled with characters, can improve with the telling. The author may or may not believe some of his own tales.

This is a book of family stories and such stories, especially when the family is filled with characters, can improve with the telling. The author may or may not believe some of his own tales.

“Grandpa Ben claimed he first met a celebrity selling her a paper: he believed that woman, who tipped him generously, was Helen Keller,” writes Colby. Think for a moment about how likely that story is to be true.

How about this story of Grandma Mary welcoming Marilyn Monroe: “After greeting each other, Grandma remarked, ‘Marilyn, that’s the most beautiful mink you have on!’ Marilyn replied, ‘You think that’s something, you should see what’s underneath.’ She pulled open the mink, and wasn’t wearing anything. Not every kid can claim his grandmother was flashed by Marilyn Monroe.” Well, every kid can claim it.

Legendary Broadway librettist Alan Jay Lerner and composer Frederick Loewe were working in a ninth-floor hotel room, below the family’s 10th-floor apartment.

“One evening, Grandpa could no longer stand the ivories tinkling in Room 908 – one light below – disturbing his sleep. He phoned the hotel operator to ask Lerner and Loewe to quiet down, complaining, ‘I wouldn’t mind if they were writing something good, but this is just noise.’ It turned out Lerner and Loewe were creating the song ‘I Could Have Danced All Night.’”

Unlike others who visited or lived at the Algonquin, Colby is not among America’s greatest writers, but his stories are well worth the read.