The signage at the site of 1,700-year-old synagogue ruins in Albania was recently replace after a Canadian tourist informed the municipal government of the old signs’ illegibility. (photo from Dave Gordon)

During a trip to Albania in September 2022, Toronto-based Jewish journalist Dave Gordon visited the city of Saranda with a couple of friends. They especially wanted to see the 1,700-year-old synagogue ruins.

As Gordon describes it, the site is roughly the size of two side-by-side tennis courts. What remains are myriad roofless stone walls of just a couple feet tall, which once separated various rooms, including a study and two mikvaot (Jewish ritual baths). A representative of Albania’s culture ministry happened to be at the site when Gordon was there, handing him a leaflet with information about the site’s history and background. It said Israeli archeologists unearthed floor mosaics – now buried with a foot of sand, to protect them from the elements – that displayed a menorah and a deer, regarded in Judaism as a symbol of beauty, majesty and God’s mercy.

Additionally, the literature said the synagogue likely crumbled after either an earthquake or a Slavic invasion, and was abandoned in the last quarter of the sixth century. In the 21st century, there was more deterioration – this time, with the printed panels describing what is on the site.

Gordon was “shocked and disappointed” to see that the signage was in disrepair, faded by neglect. Two panels, each measuring some four feet wide by two feet deep, were blanched by the sun, so white that the lettering and imagery were illegible.

“My face turned the same colour as these signs,” Gordon told the Jewish Independent, for which he has written many articles. “This is part of my heritage, my history and people, and it was like it was another Jewish landmark sadly disappearing from memory.”

On Dec. 12, 2022, Gordon took action. He Googled the Saranda municipality offices’ emails.

“This is shameful for two reasons: your tourists will not be able to obtain much knowledge about the important landmark, and it shows little care from your city’s cultural department to maintain the signage,” he wrote.

“This is highly disrespectful, and I cannot understand why the two signs were permitted to deteriorate,” he continued, adding that he hoped to bring others to Saranda and “would love for them to take photographs of the new signage and publicize this wonderful jewel of archeology.”

A representative from the municipal offices wrote back, two days later: “For the problem in question, we have reported the need for scientific reconceptualization, the preparation and installation of information panels, and we have contacted the Directorate of Cultural Heritage … a copy of your complaint will be sent to the responsible institution and we hope that very soon we will have a better presentation of this monument.”

In the beginning of January, Gordon followed up with an email, asking if the inquiry had landed in the right hands. To his great surprise, on Jan. 20, the Ministry of Culture of Albania sent him this reply: “In response to your email, we inform you that the new information boards have been installed to the Synagogue of Saranada…. Please find attached the photos of the new signage.”

Esmeralda Kodheli, the ministry’s representative, added, “Thank you, too, for promoting our cultural and historical heritage.”

“Quite amazing!” Gordon told the JI. “To print detailed signs and place them, inside of 30 working days – and during the Christmas season, no less. And who was I? Just some guy from Canada writing some emails.”

Gordon said he felt “disbelief, delight and honoured, all at the same time,” and felt like his “little bit of activism” made a tangible difference, reminding him that anyone can enact change.

“I am pleased as anything that this amazing site of Jewish history now has dignity restored,” he said.

Dr. Ruki Kondaj, one of the friends who accompanied Gordon on his trip, is an Albanian-Canadian. He said about Gordon: “He’s done great work through his lobbying to restore the signage, and I’m so happy with his passion and determination. Together we discovered traces of Jewish history that tourists will know more about.”

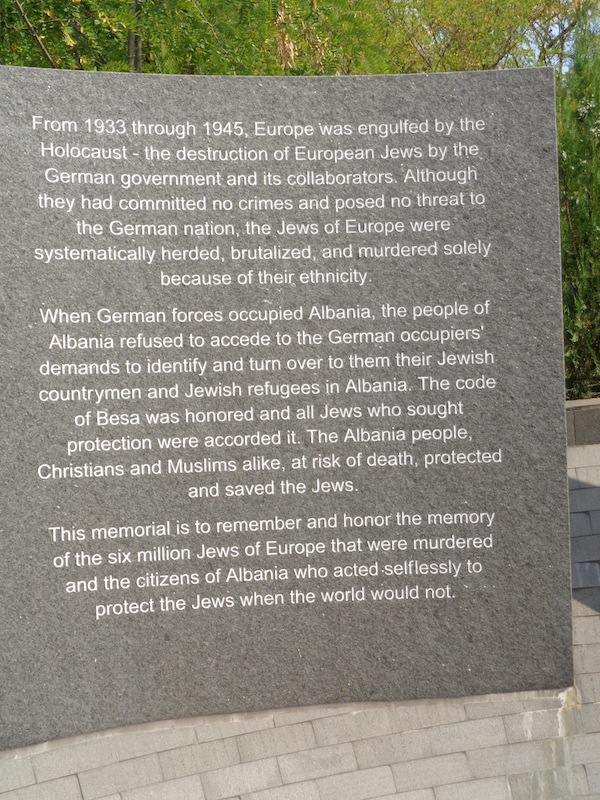

Albania has various sites of Jewish interest, including the Solomon Museum in Berat, as well as an upcoming Holocaust museum in Tirana and a future Jewish history museum in Vlora, which also is home to “Jewish Street,” marked by a plaque on a home in the city centre, marking the one-time bustling Jewish area. Albania refused to cooperate with the Nazis, deciding as a nation to save its Jews, and even welcoming Jewish refugees from neighbouring countries. For more on Albania’s Jewish history, visit jewishindependent.ca/albanias-many-legends.

Jonathan Wasserlauf is a freelance writer, and a political science major and law student based in Montreal.