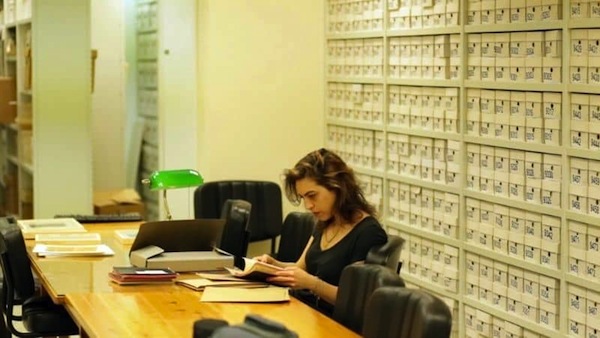

Michal Wiets uses her great-grandfather’s diaries as the basis for her film Blue Box. (image courtesy)

At press time, the Vancouver International Film Festival lineup had not yet been announced. But the Independent received the names of some of the movies to be presented, as well as a couple of screeners.

Starting with the more challenging VIFF choices, most Jewish community members will either take a pass – with a roll of the eyes as to what film festivals often consider appropriately provocative fare – or get up the fortitude to watch the disparaging portrayals of Israel, so as to be better prepared to confront the criticisms, and perhaps learn from them. I admit that I have taken both routes in life and it was with great skepticism and high anxiety that I watched Michal Weits’s Blue Box.

Weits is the great-granddaughter of Yosef Weits (aka Weitz), a Russian immigrant to Palestine in the early 1900s who was instrumental in foresting Israel, as well as purchasing land for the Jewish government from the Arabs who owned it at the time (who were mostly absentee landlords and not the people who lived on and worked the land). Depending on one’s point of view, Weits was either a legendary pioneer to be tributed, as “the father of Israel’s forests,” or a notorious pirate of sorts, stealing land from Arabs and expelling them from it, as “the architect of transfer.” His great-granddaughter seems to believe he’s the latter, while he himself was conflicted.

The basis of the documentary is Yosef Weits’s diaries, some 5,000 pages. In them, he expresses his belief in the need for the reestablishment of the Jewish homeland and his fears for Jews’ continued existence (even before the Holocaust). He also details aspects of his work, with whom he negotiated land sales and meetings with David Ben-Gurion and other Israeli leaders. Presciently, he admits to misgivings about the way in which the Arab populations were being treated, predicting that such treatment would end up causing Israel severe problems if not dealt with.

The diary entries are fascinating and reveal some of the complexities of that era and of Yosef Weits’s legacy. The archival footage and photographs are compelling and expertly edited to make clear director Weits’s viewpoint – there is no mention of events that don’t fit her narrative, such as the expulsion of Jews from Arab lands.

Weits interviewed several family members about what she discovered from the diaries and other research. Their reactions are varied, with the generations closer to that of her great-grandfather more defensive and those closer to hers, more questioning, even condemning.

It might be helpful to watch this film with a non-Jew, as I did. In doing so, I found there were a few parts – such as the Israeli government’s relationship with the Jewish National Fund and why Weits named her film after the JNF’s donation box – that could have been better explained to viewers without prior knowledge. As well, a non-Jew is perhaps better able to keep in mind that every country deals with similar issues relating to how they were established, who was displaced, etc., and that Blue Box could be seen not only as a personal tale of one family, but as the beginning of a conversation about nation-building in general rather than as a stifling condemnation of Israel.

The same may or may not be said about The First 54 Years: An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation, directed by Avi Mograbi. There was no screener available for this documentary, which is described as “a ‘how-to’ guide to civilian subjugation along ethnic and religious lines, through the example of the Israeli occupation of Palestine. This is jet black, ice-cold political satire. But the harrowing statements of 38 former Israeli military personnel must be taken at face value as eyewitness testimony of decades of state-licensed crimes against humanity.”

Thankfully, there are at least a couple of more innocuous films in this year’s VIFF. One is the short Quality Time, written and directed by Omer Ben-David. When mom goes on a brief vacation, father (Shalom Korem) and son (Noam Imber) are left on their own together, and the awkwardness of their relationship is highlighted. Imber plays a pot-dealing and -smoking teen who’s just received his draft notice, while Korem is his recently retired – from the defence ministry – father. Both actors are wonderful and the story is quirky and fun, even if it doesn’t hold up logically at the end. While Israel-specific – a gym bag being blown up by the bomb squad is a key element – it has universal meanings.

The JI always sponsors a film at VIFF and, this year, we’ve chosen the animated feature Charlotte, about Charlotte Salomon, a German-Jewish artist who created her masterpiece work – called Life? Or Theatre? (comprising nearly 800 paintings) – between 1940 and 1942. She died in Auschwitz in 1943, at 26 years old. We’ll review that film next issue.

For more on the festival, visit viff.org.