A Visit to Moscow is a beautifully illustrated and haunting graphic novel. In a brief 72 pages, it relates the story of an American rabbi who, on a 1965 trip to the Soviet Union, sneaks away from his delegation in Moscow to visit the brother of a friend – Bela hadn’t heard from Meyer for more than 10 years and was worried.

A Visit to Moscow (West Margin Press, 2022) is an adaptation by Anna Olswanger of a story told to her by Rabbi Rafael Grossman. It is illustrated by Yevgenia Nayberg, who captures in her palette, in the angles of her images, in her use of light and shadow, scratches and blurs, the claustrophobic fear that existed in that era in the USSR.

A Visit to Moscow (West Margin Press, 2022) is an adaptation by Anna Olswanger of a story told to her by Rabbi Rafael Grossman. It is illustrated by Yevgenia Nayberg, who captures in her palette, in the angles of her images, in her use of light and shadow, scratches and blurs, the claustrophobic fear that existed in that era in the USSR.

“Although the events of A Visit to Moscow are set before my time, the overall spirit of the Soviet Union feels very similar to what it was throughout my childhood when I lived there. I didn’t have to make a big leap to connect to the time period,” writes Nayberg in a section at the end of the book, where we get to see some of her preliminary sketches.

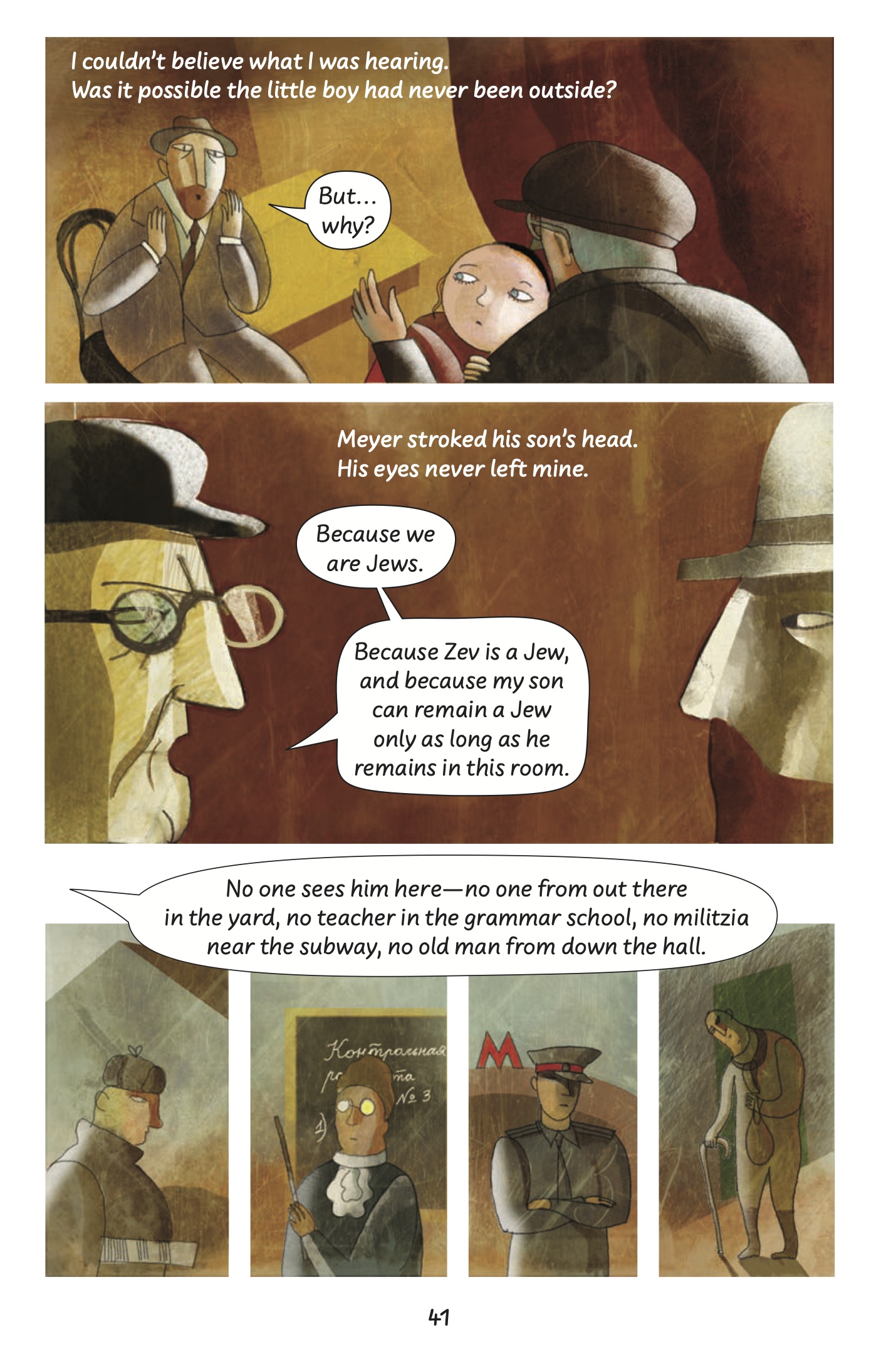

Olswanger knew Grossman, having collaborated with him on writing projects since the early 1980s. “One of our first projects,” she writes, “was a Holocaust novel with a character based on his cousin, a leader of the Jewish resistance in the Bialystok ghetto. As we planned out the storyline, Rabbi Grossman told me about an incident during a trip he made in 1965 to the Soviet Union, where he met a young boy whose parents were Holocaust survivors. The boy had never been outside the room he was born in.

“We never finished the novel, and then, in 2018, Rabbi Grossman died.”

Years later, Grossman’s daughter sent Olswanger a box of writings that Olswanger and the rabbi had worked on. It inspired Olswanger to revisit the story. But she didn’t have the whole story, so, on the suggestion of her editor, wrote A Visit to Moscow as historical fiction.

The main part of the book is incredibly moving. The tension as the rabbi makes his way to Meyer’s last known address is palpable in both text and images; the KGB are an ever-looming threat. When he arrives, it takes the rabbi time to gain Meyer’s trust and for Meyer to let the rabbi into his flat, where he meets Meyer’s wife and their son, Zev, who has never left their home. The rabbi promises to get them all to Israel.

This core of the novel is well-written, easily understood and powerful. Unfortunately, this mid-section is bookended by ambiguous scenes. At the beginning, Zev hovers from heaven over his dead body, which is laying somewhere in a mountain range. In the throes of dying, he remembers the story of the rabbi’s visit, which leads into the main story, after which we see young Zev on a plane, remembering the ride and Israel’s beauty. In the midst of this, he wonders, “And later – was it years later? Was he a young man?” In the next panel, a fire burns in the aforementioned mountain range and the text reads: “He remembers a sudden flash. A burst of black smoke. Burning metal.”

I first thought that he and his parents had been killed in a plane crash on the way to Israel, so close to freedom but never reaching it. After madly flipping pages back and forth in the book, trying to figure out what I’d missed, I found what I was looking for in the About the Contributors section: “For over 25 years, Rabbi Grossman visited Zev and his family in Israel. He saw them together for the last time in 1992, the year Zev died at the age of 37, a husband and father, while on reserve duty with his army unit in Lebanon.”

A tragic ending either way, but at least Zev got out of his room and got to live more fully for those 25 years. “Every time I visited Zev in Israel,” wrote Grossman, “he was smiling.”

A Visit to Moscow could have benefited from a few more pages, to make the transition of Zev’s journey from the Soviet Union to Israel more understandable, and to include some aspects of his life in Israel, even if they were fictional. Olswanger and Nayberg have created something special, but it feels incomplete.