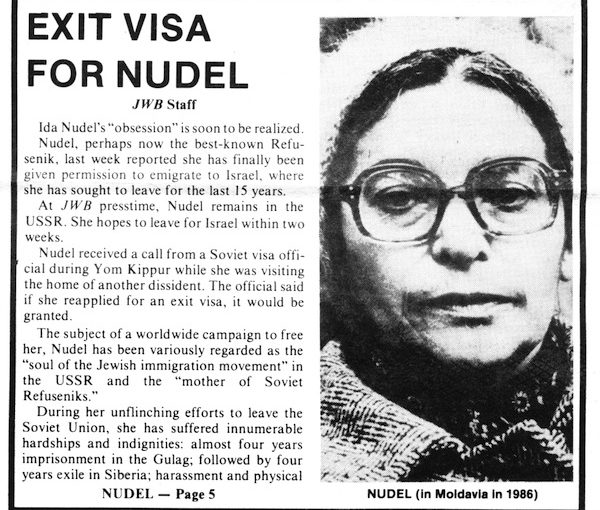

A cover story in the Oct. 14, 1987, JWB announced that Ida Nudel would be granted her long-sought-after exit visa from the USSR.

In the Jewish Independent’s special 90+1 issue this past May, reader Ronnie Tessler recalled one of the regular features of the JI’s predecessor, the Jewish Western Bulletin – the Gulag Record. Starting in 1978, the paper regularly reminded readers of how many days certain refuseniks were being held in the Gulag in the former USSR. One of the refuseniks featured, Ida Nudel, died this month, on Sept. 14, at the age of 90.

“The subject of a worldwide campaign to free her, Nudel has been variously regarded as the ‘soul of the Jewish immigration movement’ in the USSR and the ‘mother of Soviet refuseniks,’” reads the Oct. 14, 1987, JWB cover story announcing that Nudel would be granted an exit visa from the USSR.

“During her unflinching efforts to leave the Soviet Union, she has suffered innumerable hardships and indignities: almost four years imprisonment in abuse by the ever-present KGB, combined with travel restrictions amounting to incarceration,” the article continues.

“Occasionally, it was feared that, owing to diminished health, the 56-year-old Nudel would not live to see the Jewish state or be reunited with her sister Ilena Fridman, now residing in Israel.”

Fridman, the article notes, “visited Vancouver in October 1986 to lobby for Nudel’s release at a NETWORK-sponsored Soviet Jewry rally here….”

In addition to a concerted, long-term effort by Jewish groups worldwide, “urging Soviet officials to grant her an exit visa,” Nudel was visited over the years “by numerous delegations and dignitaries, including actress Jane Fonda, to bolster her spirits and encourage her efforts to leave the USSR.

“Under glasnost (openness), Nudel was allowed greater freedom to move and meet with Western journalists and fellow dissidents. Last month [September 1987], she was permitted to travel from her home in Moldavia to Moscow to meet with a group of women refuseniks to discuss their plight.”

Nudel was born in 1931, near Crimea, and “was raised by her maternal grandparents on a collective farm until she was 3,” writes Sam Roberts in the New York Times article about her death. “Her father was killed in World War II fighting German troops near Stalingrad when she was 10.

“After graduating in 1954 from the Moscow Institute of Engineering and Economics, Ms. Nudel worked for a construction company and later as an accountant for the Moscow Microbiological Institution,” notes Roberts.

As a result of her protests in the 1970s, Nudel lost her job and was exiled. When her exile ended, she settled in Moldova. After she was allowed to make aliyah, Nudel “originally lived in a rural settlement,” writes Roberts, “then moved to the city of Rehovot, about 18 miles south of Tel Aviv, to be closer to her sister [who had been allowed to emigrate in 1972].”

Nudel wrote an autobiography, A Hand in the Darkness, which was translated into English, and there was a movie made about her experience.