Almost every Holocaust survivor’s narrative involves some combination of extraordinary coincidence, righteous humanity amid dystopia or a series of chance events that astonishingly result in survival against all odds. The number of such flukes in the life of Vancouver woman Malka Pischanitskaya may convince readers of the author’s conclusion that survival was her destiny.

Pischanitskaya’s memoir, A Mother to My Mother, is one of the latest releases in the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program. Begun in 2005, the program has now published scores of firsthand testimonies of Canadian Holocaust survivors, many in both official languages, and all of them available free of charge to educational institutions.

Pischanitskaya’s memoir, A Mother to My Mother, is one of the latest releases in the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program. Begun in 2005, the program has now published scores of firsthand testimonies of Canadian Holocaust survivors, many in both official languages, and all of them available free of charge to educational institutions.

Pischanitskaya’s Ukrainian Jewish family knew its share of misery before the emergence of Nazism and war. Her father abandoned her mother before Malka was born, in 1931, and she was raised in grinding poverty by her grandmother and great-aunt while her mother worked in a nearby village and saw Malka some weekends.

The Stalinist-induced Ukrainian famine of the 1930s killed between three and five million people. The Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, and its perpetration of the “Holocaust by bullets,” killed 1.5 million Jews, mostly shot at close range and buried in mass graves.

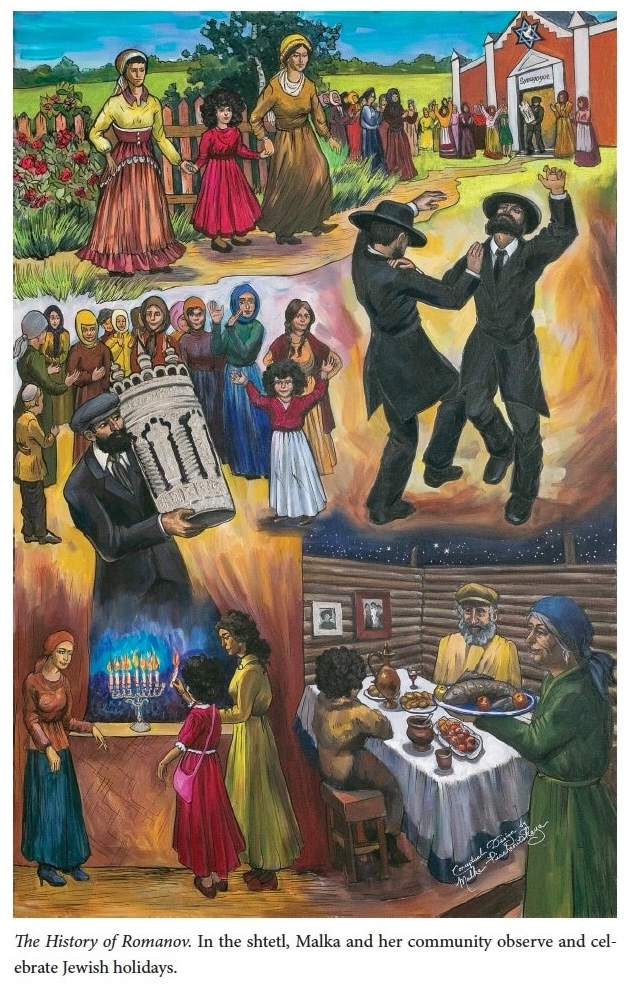

Young Malka’s earliest life, despite hardships, was not without happy memories of Jewish holidays and the changing of the seasons. These are tempered with stark recollections. Without electricity or anything but firewood for heat, she recalls Ukrainian winters so cold the ink at school would freeze solid.

After the Nazi invasion of Poland and the beginning of the war, in 1939, five refugee families from Poland arrived in Romaniv (alternatively: Romanov).

“I have often wondered how much my community found out from these refugee families about what was happening under the Nazis in Poland and whether this made them more aware of the disaster that was to come,” writes Pischanitskaya.

What was to come was beyond imagining – which may help explain why Malka and her family remained in Romaniv when some other Jews fled further east into the Soviet Union.

“We were not ready – there had been no mental preparation for this moment – so we did not accept the offers to escape,” she writes.

Soon, the Nazis arrived and young Malka witnessed Jews being killed in the streets. The randomness of those murders was replaced with methodical mass executions. The story, starkly told, is predictably shocking, and differs significantly from what happened further west. Rather than ghettos and concentration camps, the Holocaust in the east was typified by summary roundups and mass killings of entire communities, usually in adjacent forests.

On Aug. 25, 1941, Ukrainian police gave Romaniv’s Jews 30 minutes to congregate in the centre of town.

“Those who were unable to walk had been taken out of their homes on stretchers,” she writes, disabusing Jews of the desperate idea they were being assembled to perform forced labour.

“We walked toward the beautiful park located a couple kilometres from the centre of town,” writes Pischanitskaya. “The crowd of close to 2,000 walked with visible sadness, expressions of disbelief.

“Men were rounded up, separated from their families, and then marched deeper into the forest where, previously, pits both massive and deep, had been dug. Women, children and the elderly were forced into rooms in the military building. Crowded in, there was hardly space to stand. Windows were locked. No fresh air; no water; no washrooms. People screamed, fainted, losing their minds; children were scared and restless.

“One by one, several groups of Jewish people were taken to slaughter. While we were kept in the building, waiting our turns, the heavy ring of machine gun fire instilled extreme fear and terror in all. The slaughter of the Jews from the Romaniv community continued from early morning until dusk – the sun had faded from our lives forever.”

Then: the first of the miracles that spared the life of Malka and her mother.

“Eventually, mothers with children were let go from the building,” she writes. “Perhaps the murderers were tired from their orgy of death and torture, or perhaps there was no room in the pits for the rest of us, but those who had to remain were slaughtered. We left them, still alive, when we had the chance to run for our lives.”

Here, Pischanitskaya catalogues the names of the many family members killed that day. She goes into grim detail about what witnesses reported from the pits.

Thus began years of hiding – and a succession of near-misses, any one of which would likely have been fatal.

The relationship that gives the book its title, of young Malka mothering her mother, is a story of a parent so paralyzed by events that she becomes almost incapacitated. Malka’s astonishing and perilous actions to ensure their survival form the bulk of the book. She begs door to door in the villages where they hide, often receiving small portions of food. At one home, she sees her own portrait on the wall, apparently pillaged from Malka’s family home after they fled – an uncanny and grotesque coincidence.

When, after the war, they returned to Romaniv, “Almost nothing remained except for memories.”

“Adult survivors went to the mass graves to pray for and memorialize their loved ones, and to bear witness,” writes Pischanitskaya.

Of all the people who survived and showed up alive after the war was Malka’s “so-called father,” as she calls him, a man whose sadistic cruelty Malka and her mother would have been better off without.

In a twist, the mother who had been “a dependent child” transformed into a courageous woman who pursued Polish and Ukrainian police for war crimes.

Like so many survivors, Pischanitskaya demonstrated improbable resilience, marrying, becoming a teacher, becoming a mother, escaping the Soviet Union, migrating to Canada and raising a successful family that continues to contribute to Vancouver’s Jewish and broader community.

A Mother to My Mother is illustrated with harrowing, moving paintings that Pischanitskaya created for an exhibition titled Romanov: A Vanished Shtetl, which was presented at the conference of the World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust and their Descendants, held in 2019 in Vancouver.

To order a copy of A Mother to My Mother in print or ebook format, or any other survivor memoir, visit memoirs.azrielifoundation.org.